By Emma Crichton-Miller

THIS WEEK, FRIEDMAN Benda opened their fourth solo show of work by British designer Paul Cocksedge. Titled ‘Performance’, it features three new series of work, each a conceptually elegant playing off of one material against another, with paired displays of objects dramatising the processes involved in their creation.

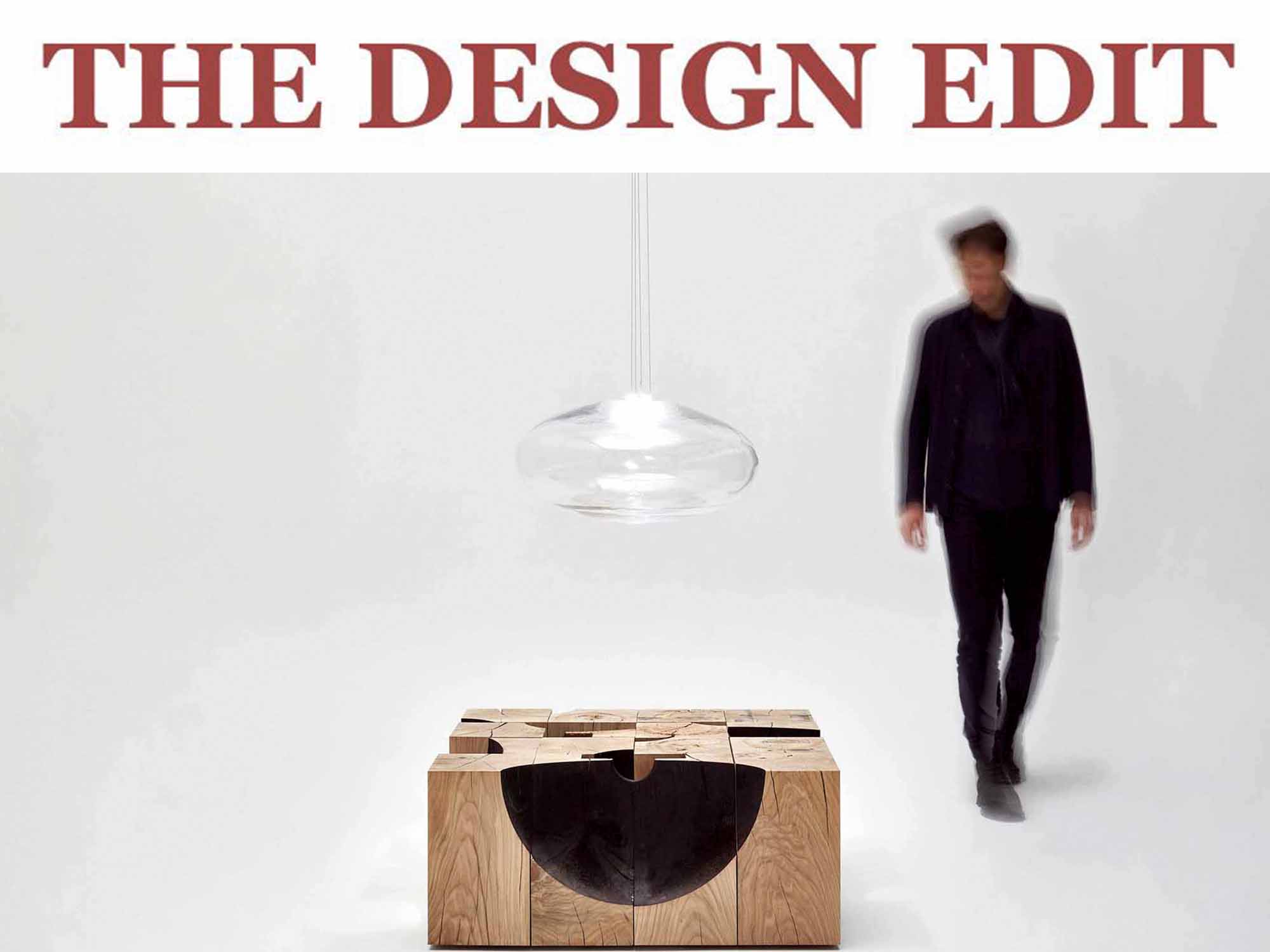

Lights are hung above the moulds used to create them, now cut up and rearranged as tables, inviting us, the audience, to imagine the fire and smoke involved in their birth. For the ‘Push’ series, we are asked to imagine the tension in the steel, twisted like an ice-cream cone or paper trumpet to fit through the opening in a large block of concrete and then allowed to unfurl.

For ‘Performance: Excavation’, Cocksedge has revisited his much-admired ‘Excavation: Evicted’ series, for which he assembled furniture from concrete cores mined beneath his studio. Here, the cores have been sourced from construction crews operating across the British Isles during the 2020 lockdown – a reminder of the essential activity that continued during the last year, while all inessential work was shut down and office workers were confined to their homes. Above, hangs a lighting fixture blown using the gaps between the cores as moulds.

With an irony not lost on the London-based designer, Cocksedge was unable to be there himself to direct the show’s installation in New York. Instead, he talked The Design Edit through its conception. “Making is very much part of the meaning of the show,” he explains. A multifarious designer, who has a special affinity with glass and light but works with many different materials, Cocksedge is frequently the bystander in his own production, watching skilled glassblowers and metalworkers realise his ideas.

“Because I am an observer, and so not completely involved in the process of making, I can see the technicians’ hands touching first wood, then metal; steel then concrete.” He wanted to bring this tactile immediacy to his audience. By reconfiguring the moulds after use, so it is not immediately obvious how the lights are made, Cocksedge also wants to involve the audience conceptually in the process: “You have to decode how the glass was made. The shapes are not literal, not obvious – they become very abstract. People get to appreciate the curves, the shadow play.”

Cocksedge explains he also loves the pairing of opposites – “the contrast between heavy objects and the floating, hanging objects; the dark steel and the pale concrete.” There is also the pleasing economy of means, creating furniture and lighting with minimal materials, without waste.

During the making of the show, Cocksedge recorded the sounds in his workshops – the roar of fire, the pouring of cement, the twisting of metal. “It is as exciting as the finished pieces,” he comments. The recording will play in the gallery for the duration of the exhibition. “It will allow people to connect with the pieces more deeply,” he says.