By Tiffany Lambert

Today’s designers are coming to terms with the existential conundrum of our late-capitalist age. In the 21st century, Europe and the United States have largely transitioned from industrial manufacturing economies into globally networked societies. New methods of work and social organization have replaced old hierarchies and 20th-century power structures as the last remnants of the industrial age begin to dissolve. Post-Internet irreverence towards established rules and tastes has fundamentally shifted the contents and context of our designed environments. While most large design companies grow ever more conservative, rarely taking chances on experimentation or less-established names, young designers are devising their own unconventional paths, forgoing the traditional mass-produced route for the customized, the niche, and the handmade. From scavenging among the vast amounts of waste produced by the present crisis comes what we might call “trash aesthetics.”

A number of relative newcomers to the design scene have begun to rejig design history, discovering new production possibilities and stylistic signification. Figures such as Anton Alvarez, Thomas Barger, Chen Chen & Kai Williams, Misha Kahn, Kueng Caputo, Max McInnis, Matthias Merkel Hess, Chris Schanck, and Katie Stout (as well as artists like Jillian Mayer and Jessi Reaves) can be seen moving away from the formalist aesthetics of Postmodernism, instead using what is more immediately at hand to question the validity of functionalism and industrialization. Their motto could be “form follows process,” as Brooklyn-based Chen & Williams have suggested in reference to their own approach to design practice. While all these designers maintain their own idiosyncratic methodologies, there are common elements to their practices when examined collectively.

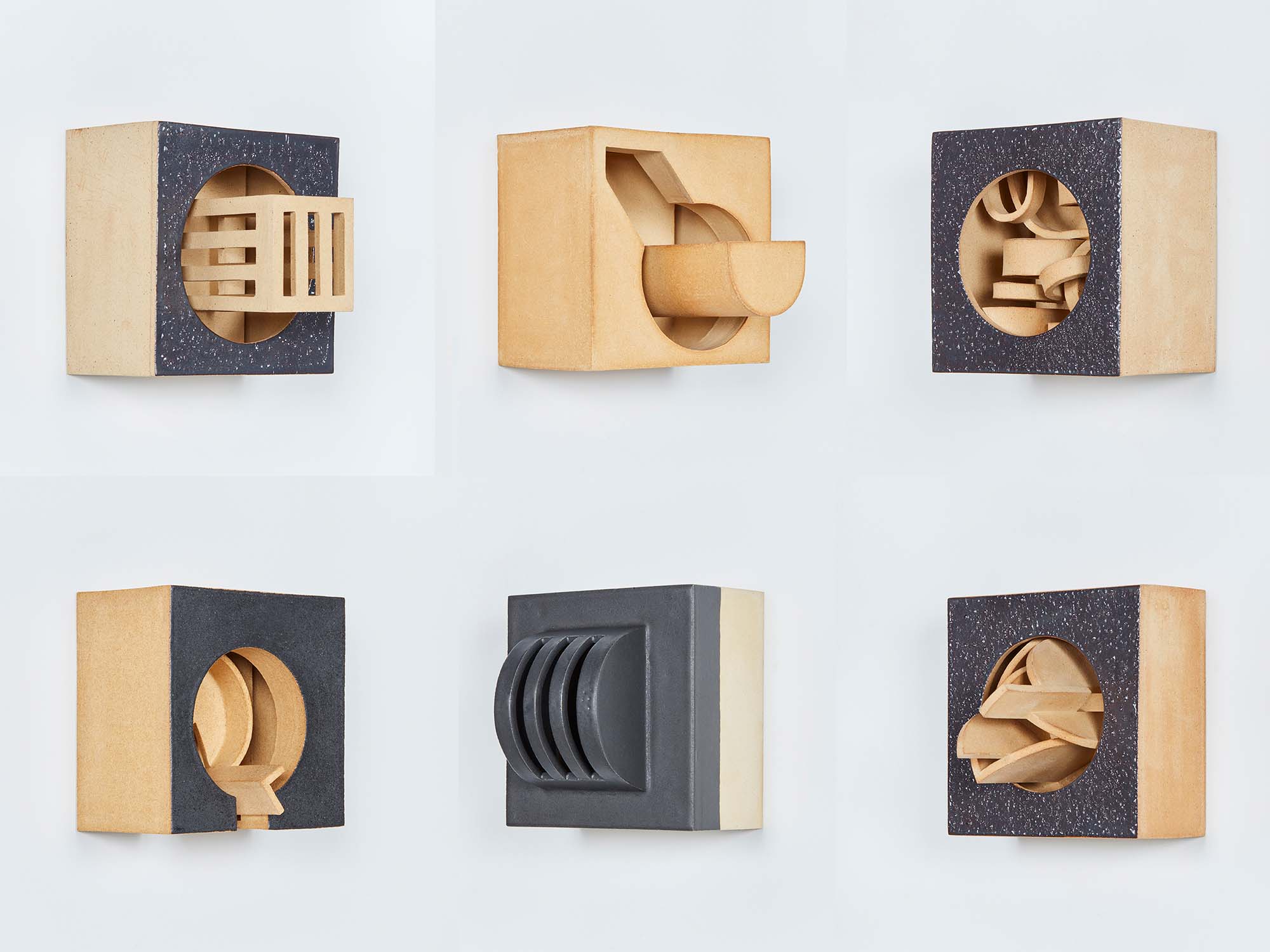

Each employs an improvised, process-driven approach that involves the deliberate removal of their work from the traditional methods of industrial mass production and heavy experimentation with materials, themes, and concepts, resulting in an emancipative assemblage that resists hierarchical preference. In their hands, machine-made forms are not favored over embroidery, nor are natural materials like clay privileged above manufactured resin. Their work evinces new strategies for creating meaning in design, mixing materials and methods: mass-produced with hand-made; patterned with plain; colorful with austere. This grab-bag approach frequently eschews perfection and, in its celebration of anti-beauty, overlaps with what’s been anointed “ugly design” — a term coined in recent articles published in Artsy and The New York Times in order to describe and make sense of a wider delight in the distasteful in both furniture and graphic design (as evidenced by the hugely popular Instagram account @uglydesign).

The output of contemporary trash-aesthetic designers is inseparably linked with the design of decades past. Just as conceptual Dutch design of the 1990s by the likes of Droog could not have existed without the pioneering work of Memphis or Studio Alchimia, or without the contributions of Postmodernists and punks, so too does this new group stand on the shoulders of intellectual pioneers of design history. Collectively, they spring from an understanding of both Modernism, where the aesthetic largely celebrated the possibilities of the machine and new industrial materials, and Postmodernism, where the object or piece of furniture became an intellectual pursuit — the form itself was the vehicle for cultural commentary. As with the fragmentation of culture over the last two decades — new communications technologies have splintered and segmented audiences and markets, radically dividing our political, economical, and social realities — so contemporary design discourse lacks a cohesive critical discussion about new mentalities emerging within the field. We find ourselves at a juncture in history when grand narratives appear to have fallen silent. Among this multiplicity of aesthetic cultures is a contemporary-design field so vast and diverse as to resist and frustrate historical summary. Nonetheless, while it may be too soon to fully historicize developments as recent as the last five or even ten years, it is perhaps not too soon to initiate a theory with respect to one particular thread in this multitude of realities.

Broadly, work that might be labeled trash aesthetics employs found, natural, and synthetic materials, pop-cultural references, and what seem like slapdash procedures to mock — and simultaneously exploit or ignore — previously glorified industrial processes. This new wave of design glamorizes the aesthetics of DIY, of the everyday, and of the haphazard homemade. Trash aesthetics is an experiment in producing alternative designs and alternative pedagogies. These practitioners seem to approach the design process in a way that renders the physical appearance somehow secondary, instead emphasizing the improvisational process. They are ideological revisionaries. It is not difficult to imagine their role as modern-day bricoleurs, sifting through the post-industrial debris and embracing techniques both old and new to serve as means to their ends.

Stout, for example, often distorts and erases the function of her designs: is this vibrant hot-green triangle with a light bulb stuck onto it a lamp? What about this pastel-pink mound? What makes a lamp a lamp anyway? Stout, whose studio is located in Brooklyn, makes no presumptions on the form of her outcomes. She’s motivated by her experience of the process and her latest projects are the result of experimental collaborations with artisans — a wicker weaver, a stone fabricator. Even when it’s not a strictly individual endeavor, this approach still privileges the personal experience and the narrative of an object’s creation. Her signature Girls (2017 onwards), molded from ceramic and resin, seem to sashay away any conventional ideas of functionality and purpose (more on this later).

Broader collective narratives are evident in the respective practices of Barger and McInnis. While their work differs in important and obvious ways — McInnis reconfigures kitsch Midwestern iconography; Barger crafts misshapen furniture from found objects — they both hail from the American Midwest (Iowa and Illinois respectively). In fact, many of the trash-aesthetic practitioners came of age in the sort of places characterized by identical suburban strip malls, big parking lots, and chain stores like Walmart and Home Depot, a landscape defined by the post-World War II American dream and accelerated economic expansion. But these are also the places where the demise of this dream is the most palpable, rust-belt towns that have suffered the most from the decline of traditional manufacturing industries. Now that it’s been revealed that this American dream is trash, these designers are conceptually trying to use its refuse to imagine something new, on a more personal scale.

And then, more literally, many of these designers have a practice of bricolage and incorporating found objects in their work. Chen and Williams, also based in Brooklyn, reclaim scraps from their own studio — resin, wood, epoxy, bone, rope — to discover novel and repurposed uses. In their ongoing Cold Cuts series, material leftovers are combined into a sausage-like form, hardened, and then sliced up into coasters. Their approach speaks to their ability to make meaning out of the discarded, a direct countermeasure to traditional industrial design. “When we started our studio, we didn’t have the money to buy slabs of stone or hire machinists to make highly accurate parts,” the duo admits. “Our hand skills were limited as well because our design education wasn’t craft-based, we were trained as generalists. We had to create value by taking common materials and combining them in an unconventional way where the sum was greater than the parts.”

Meanwhile recovering materials from the roadside, the beach, or recycling centers has also been central to Kahn’s practice, especially in his earlier work. The Duluth, Minnesota-native uses these orphaned parts to create new compositions. Kahn, now also based in Brooklyn, objectifies the original materials while simultaneously elevating them into their own nuanced evocative forms. Formulating a visual vocabulary based on intuition, Kahn’s works are exercises in experimentation — his objects embrace the unlikely aesthetic of the direct process from which they were born, often collapsing the hard industrial with the soft organic, the digital with the physically tangible. A sense of nostalgia is reimagined too: Kahn uses the ubiquitous inflatable furniture he saw while growing up to cast mirrors, stools, and tables in resin and concrete, lending a lightweight airy structure to permanent and weighted materials.

Another example is Detroit designer Schanck. In his Alufoil series, he revives mundane materials such as found wood and scavenged industrial parts through a transformative process of wrapping them in aluminum and applying resin to create assemblages. The deliberately improvised approach also nods to potential interpretations that might be discovered in existing objects. “All of my collective experiences as an artist and model maker taught me an important thing, that if you are committed to something ordinary, you may be able to create something extraordinary. I appreciate my life and built environment best when it has contrast. The historical and contemporary are the sweet and savory of life, there is room for all I think,” he offers by way of explanation. His approach is flexible and can take on almost any typology, and community is also critical to his practice — Schanck continuously invites students and local craftspeople into his studio to collaborate on projects.

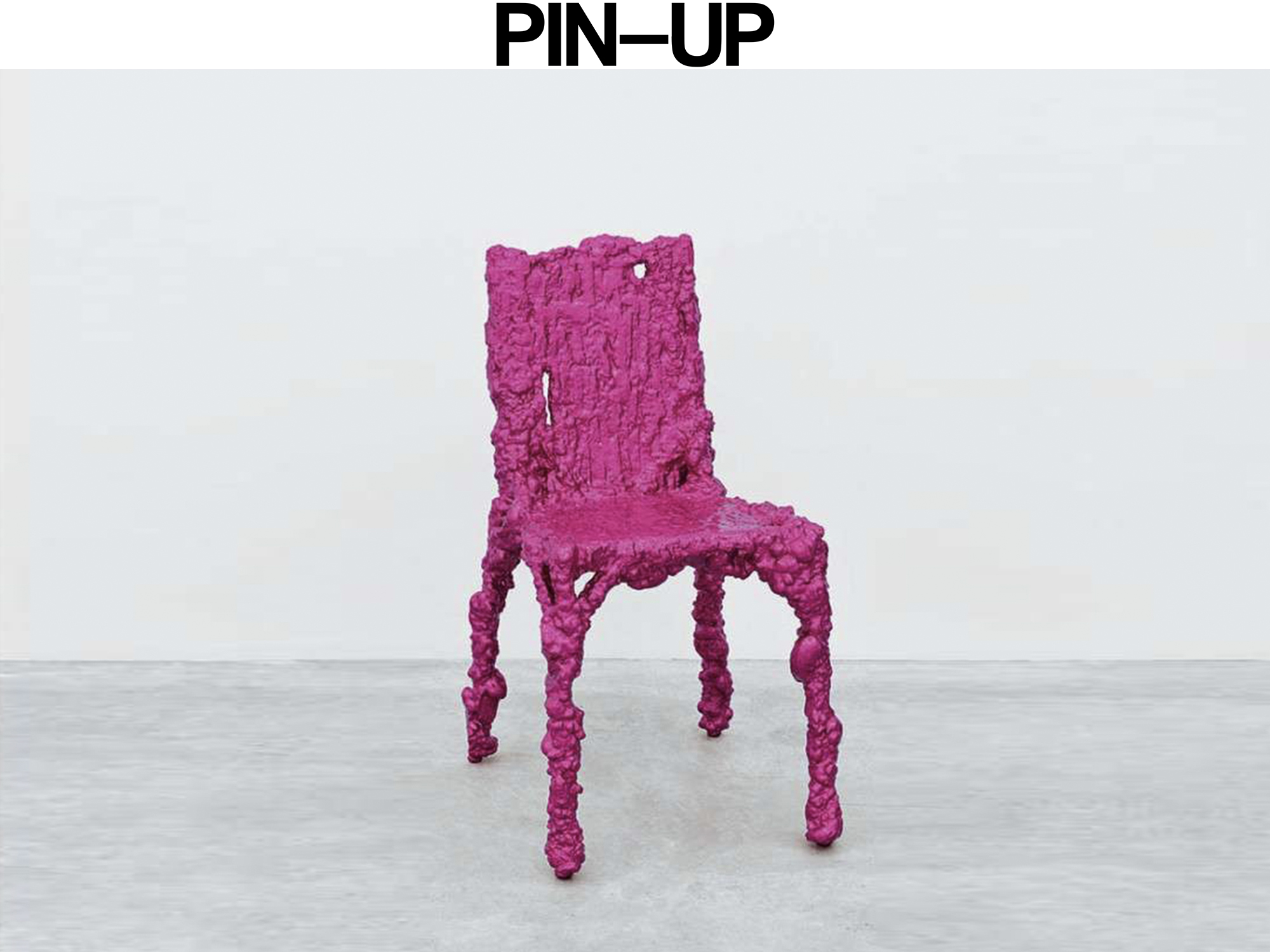

An overt questioning of the traditional role of the designer as independent creator is once again evident in the work of Chilean-Swedish Alvarez, whose creations include furniture and lamps that are made by machines of his own invention. Alvarez — like many others in this loosely affiliated group of trash-aesthetic practitioners — works in part to unseat the creator as the sole producer of a given work’s significance and meaning. In his Thread Wrapping series (2012 onwards), basic materials such as wood, electrical cords, and PVC tubes are woven together using only glue, thread, and pigment. Another project called The Extruder (2016) forces wet clay through molds into what resemble spontaneous ice-cream piles. The work reflects on its own chance methods of production and consumption, and highlights a tension between the role of the designer as both craftsman and engineer. It is noteworthy that among this group, Alvarez is the only non-American designer.

New York-based Reaves is also an exception in another way, self-identifying as an artist, not a designer, and showing in an art context. (Reaves originally studied furniture at the Rhode Island School of Design before graduating in the painting department.) Her Frankensteinian upholstered creations use the materials and processes of industrial design but subvert them to create assemblages that challenge the boundaries between furniture and sculpture. In one piece shown in Midtown, an exhibition co-produced by Salon 94 and Maccarone at New York’s Lever House in the summer of 2017, Reaves deconstructed and reconstructed an electric fan. Taking an existing object and adding to it, she reinvented its original form by combining sawdust and glue, a technique she exposes as an outright aesthetic, were furniture makers traditionally use it to cover up imperfections like dents and gaps in their wooden works. A more recent piece, Black Night Woman, created for her 2018 residency at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, consists of an unevenly shaped fiberboard shelf covered in a soft zip-up techno fabric with fin-shaped extrusions. Against the backdrop of one of the 20th century’s most revered architectural landmarks, placing a sculpture of low-cost, off-the-shelf industrial materials with fashion fabrics is nothing short of a provocation.

Another artist interested in functional sculpture is Miami-based Jillian Mayer. Her idiosyncratic path underscores both realities of collectability and the trash aesthetic’s post-Internet context. Mayer’s practice originally focused on new-media work and her first foray into functional sculpture was her Slumpies series (2016 onwards) — seating designed to support the body in a smartphone-induced hunchback position. While they share the same conceptual concerns as her digitally based work, these functional sculptures are much more collectible. And while many of the trash-aesthetic designers are not making work about the Internet in the same way as Mayer, the fetishization of the handmade in their haphazard, imperfect, slapdash, and self-consciously material design works does feel like a direct reaction to smartphone- and computer-driven lifestyles. Moreover, and on the other hand, nearly all of the design practices operating within the framework set out by trash aesthetics suggest a hyper-reality of oversaturated, vivid colors and an intensity of tangible materiality that references the overtly technological age from which it comes.

The decision to show functional furniture in an art context may be the exception, but it draws attention to the way that art and collectible-design markets intersect today and how new industry norms have played a role in the way the trash phenomenon has developed. (Without exception, all trash-aesthetic practitioners operate within the markets of collectible art and design.) Throughout the aughts, new markets were established within the realm of design. The inaugural Design Miami/Basel — following the Art Basel conglomerate of art fairs — first took place in 2005. The Istanbul Design Biennial was introduced separately from the art world’s Istanbul Biennial in 2012. The London Design Biennale started in 2016. Many smaller regional design fairs, biennials, and triennials, as well as auction houses that specialize in contemporary design, have proliferated. With the establishment of these events on the cultural calendar, straddling both the worlds of art and design, collectible design became a more commonly acknowledged commodity to a degree it was not before.

These new markets have had an impact on the value of one-off works. While the major movements that define post-war design prior to 2000 have in the common the ambition to see their work be industrially produced, the new movement’s central impulse is the creation of unique pieces; an irony given that trash aesthetics is a counterpoint to, or result of, the decline in traditional manufacturing and industries that placed America in its critical position at the forefront of global design from the 19th and 20th centuries. Not to mention the irony that most of the work is sold to members of the so-called one percent that are often held responsible for the demise of the very industrial-era economy whose aesthetic tropes trash practitioners now exploit for their work.

A particular strength to be found in the work of trash-aesthetic designers is that while it is frequently associated with kitsch, it goes beyond the irony and pastiche of Postmodernism (or the one-liners of conceptual Dutch design) through the inventive use of salvaged materials and a sensitivity to their specific process. Often, this process involves the narrative potential of the approach adopted. “There is another relationship beyond just seeing the finished object, but seeing the story of how it is made. This creates another level of understanding,” says Alvarez in discussing his work’s intended effects. Examples of trash aesthetics evidence a new strategy for the creation of meaning in design today. Rather than being simply about a renewed sense of craft in response to globalization, there is a shift in the understanding of what narrative structure a design can embody: trash-aesthetic objects focus on gesture and emotion, questioning the role of the object and sometimes also of the figure of the “designer.”

Some designers are able to go beyond their own methods and processes in order to articulate additional meaning — social, political, and critical. For too long the importance and historic contribution of women designers has gone understudied, unnoticed, or just been plain ignored. In response, Stout and Reaves, for example, address continued issues facing female sexuality and gender discrimination. Stout’s aforementioned Girls series consists of lumpy anatomically female clay figures that serve as mirrors, lamps, shelves, and even toilet-paper dispensers. They connect the handmade object to notions of the male gaze and gender stereotypes, commenting on how the female nude has been mistreated throughout art and design history. With Girls, Stout powerfully appropriates those forms and ideas, taking them back to serve her purposes. And then with Executive Wage Gap desk (2017), hot pink in color with a cracked surface, Stout nods to the broken system and inequality that women experience in the workplace. In a similar vein, Herman’s Dress by Reaves, shown during the 2017 Whitney Biennial (exhibited as a work of art but encouraged to be used as furniture), consisted of Herman Miller’s 1967 Eames Sofa slipcovered in translucent pink silk, a provocative alteration that lends an otherwise safe Modernist piece by two industry titans a sense of camp and eroticism.

Taken together, trash aesthetic practitioners create their own versions of a fantasy where private mythologies become radical realities, and individualism is favored over communal ideals. In an increasingly pluralistic world, this new generation of designers is borrowing from the past in order to find the new in the present. The clash of high-low, of the urban and suburban, of the kitsch and the banal, of the natural and the artificial, and their embrace of both chance and a singular, excessively individualistic perspective, shrug off stylistic idioms and create a deliberately heterogeneous aesthetic. Their unabashed faith in the amorphous, the fragmentary, and the hybrid reflects the chaos and multi-layered contingencies of post-industrial, late-capitalist society. Such unhindered experimentation opens doors to new and real values of self-authorization.

There exists an unresolved tension between aesthetic aspiration and sociopolitical reality; a tension between collectible design being what the name suggests (i.e. profitable, has an established market) and the economic contexts within which the work is realized (the shortcomings of Western industrialized culture). Trash aesthetics are a radical opposition to former conventions, working to upend the idea of polished mass-produced work and its corresponding values. Its practitioners are now rummaging through the remnants of a failed vision of society. In proposing — through design — their own paradigm within the present neoliberal crisis, the practitioners of trash aesthetics are the contemporary avant-garde. Their work is an exercise in self-preservation through adaptation.