By Evan Nicole Brown

The monomyth, or hero’s journey, is a classic storytelling arc: A person is called to action and challenged by adventure, ultimately emerging transformed. Ini Archibong, the Nigerian-American artist and designer, is on a hero’s journey of his own these days, as he presents a constellation of new projects, pieces, and collections around the world. Each one is an exercise in place-making, carving out space for a Black aesthetic universe that has previously been underexplored by the mainstream.

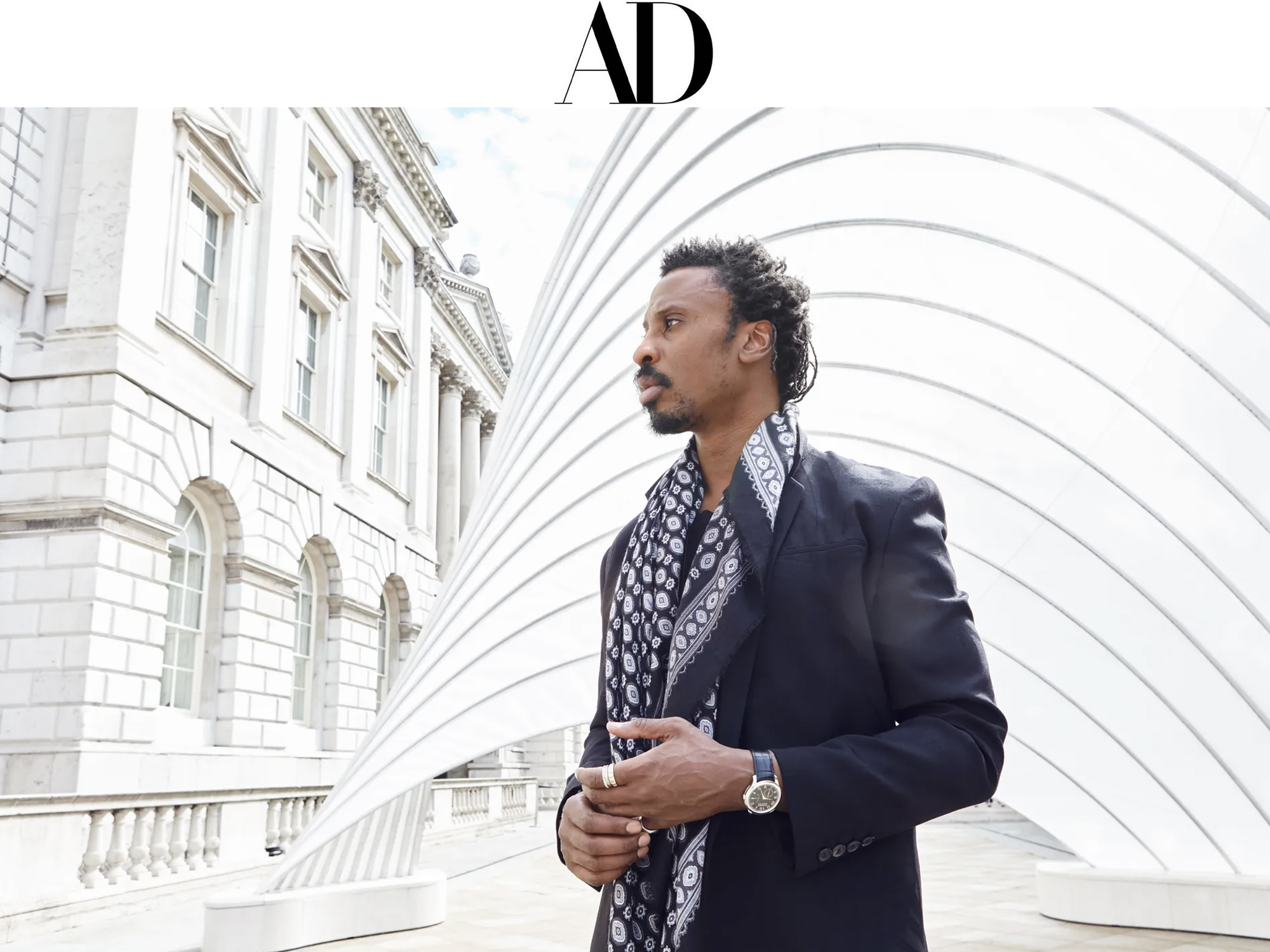

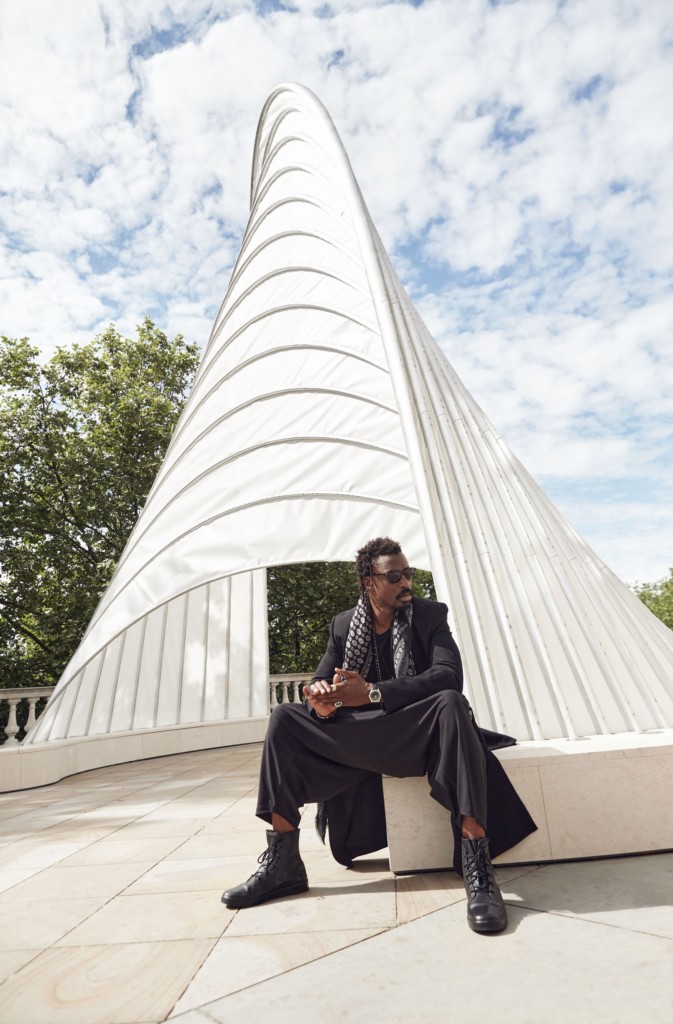

At the London Design Biennale this past June, Archibong debuted the Pavilion of the African Diaspora, the first of three architectural follies—part-sculpture, part-temporary monument—called The Sail, The Wave, and The Shell. (The latter two will be unveiled in New York and Miami, respectively, later this year.) Realized with the help of project manager, Tamara N. Houston and architectural oversight from Perkins&Will, the swooping structure, made of aluminum, sail fabric, and stone, won this year’s best-design medal. A gathering space and forum for cultural programming on the River Terrace at Somerset House, it builds on Archibong’s interest in how Black people have been displaced around the globe—the Middle Passage as a shared odyssey. It’s a topic that dovetails with resonance, the theme of this year’s Biennale. “I thought about the reverberations that our creative voices have around the world,” notes Archibong, speaking by phone from Switzerland, where he has lived and worked since 2014. “Every time a reverberation comes from any corner of the globe, from a member of the diaspora, it affects the world. It’s almost like a rallying call.”

Archibong grew up in Pasadena, California, and studied environmental design at ArtCenter College of Design. As he recalls, “The furniture I was making wasn’t understood at first, because it was art as furniture.” Jerry Helling, the president and creative director of Bernhardt Design, who was teaching a studio course at ArtCenter, became an early champion. Bernhardt eventually put the table that Archibong made with two classmates (he was behind the sculptural legs) into production. In the decade since, more commissions and collaborations have taken shape, among them a watch for French luxury brand Hermès and an array of pieces for the London-based furniture maker Sé.

Three years ago, Knoll, the renowned American brand, tapped Archibong to create new furniture for them, set to launch in January. Mass production hadn’t been Archibong’s primary focus, but he was excited by the opportunity to design for a new scale—taking cues from Scandinavian modernism and midcentury icons like the molded-plywood Eames lounge chair. “I’m drawing from all those things to make a singular, monolithic representation within the chair,” Archibong notes of his new collection, which includes an indoor-outdoor table and café chairs. Following AD 100 architect Sir David Adjaye, he is the second Black designer to join Knoll’s legendary roster.

Still, it’s Archibong’s sculptural approach to form-making (and the medium’s capacity for storytelling) that sets him apart. Four years after Marc Benda, of the New York gallery Friedman Benda, began working with Archibong on a glass-and-brass chandelier, their collaboration has evolved into a solo show of Archibong’s most experimental pieces to date. “The gallery work is the most personal part of my work,” he says of the new exhibition, on view October 7–November 2. “There’s no brief; it’s just me expressing myself and my feelings through objects and the messages that I want to convey.”

Allowing his personal evolution to inspire the results, Archibong has created a collection that is the manifestation of different points along his parallel creative journey. Materials like marble, glass, brass, and obsidian wink at the heaviness and lightness of life, their coexistence inevitable. The Manna chandelier is a dynamic arrangement of glass orbs whose oblong forms are mirrored in a console of the same name. And the colors that seem based on ones found in nature (a vermilion sunset, a navy sky) appear all the more saturated as light filters through the glass. Two illuminated stone obelisks—one black granite, the other white marble—emanate a stable, smoky glow while nodding to the reverential monuments of Ancient Egypt.

Though Archibong’s projects may differ in scale and scope, his endgame remains the same: to design his way into history, while giving form to the limitless abstraction of the Black experience. In a sense, he is like a visual griot—a storyteller in West African culture who uses language to build worlds and preserve history. “Because there isn’t a canon of what the diaspora is, as a unified entity, it gives me the opportunity to invent it,” reflects Archibong. “With a certain part of my work I’m creating mythology for the diaspora that can stand on its own.”