By Pilar Viladas

When it opened in October 1969 at what is now the Smithsonian American Art Museum, in Washington, D.C., the groundbreaking exhibition “Objects: USA” introduced American audiences to the studio craft movement. Organized by the farsighted New York art dealer Lee Nordness and Paul J. Smith, then the director of the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts and Design) in New York, it presented more than 500 pieces by 308 American artists working with traditional craft materials like ceramics, glass, wood, fiber, and metal, but often using them in a way that was much more connected to contemporary art movements like Abstract Expressionism, Pop, and California Funk.

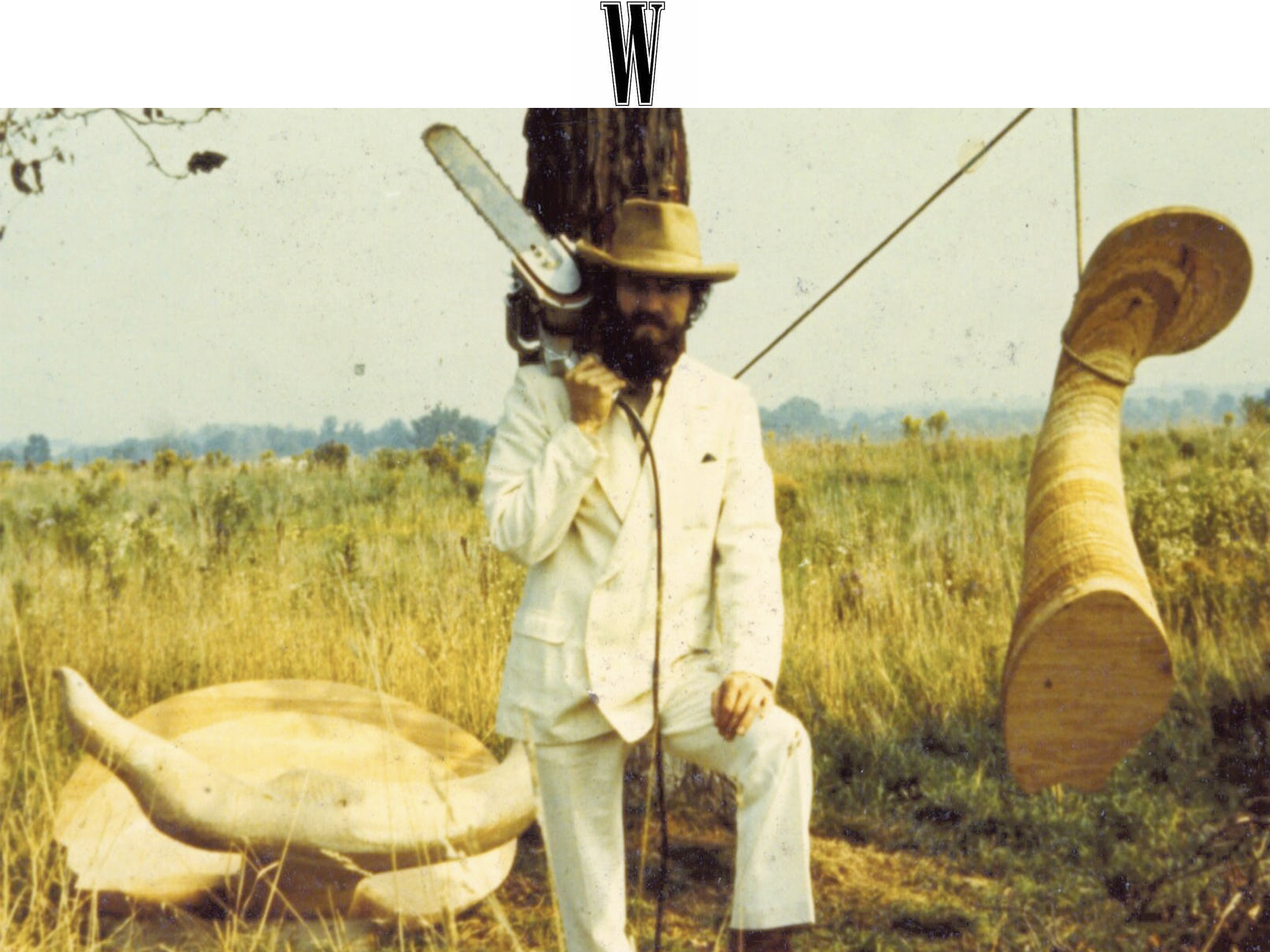

“Objects: USA” was notable for its unusual diversity of geography, gender, race, and ethnicity, and it included works by established masters (the furniture designers Wharton Esherick and George Nakashima; the glass artist Harvey Littleton; the ceramicists Gertrud and Otto Natzler), contemporary mavericks (the ceramic artists Peter Voulkos, Ron Nagle, and Doyle Lane; the furniture designer Wendell Castle; the fiber artist Sheila Hicks), and those, like the multimedia artist Michele Oka Doner and the glass artist Richard Marquis, who were just starting their careers. There was even a nun, Sister Mary Remy Revor, whose woven and printed textiles won her many awards and a Fulbright scholarship. The array of works later traveled to 33 venues in the U.S. and Europe.

Over the subsequent decades, the studio craft movement gradually lost its momentum, but the show and its accompanying 360-page book, also titled Objects: USA, were not forgotten. In fact, they have taken on a new relevance. Just ask Evan Snyderman, a cofounder, with Zesty Meyers, of R & Company, the New York gallery known for celebrating the work of both 20th-century modernist and contemporary makers. “Objects: USA 2020”—featuring 50 of the artists from the original show and 50 contemporary artists—opens on February 16 at R & Company and runs through July. “I’ve had the catalog for ‘Objects: USA’ on my bookshelf for as long as I can remember,” Snyderman says, adding that today it “seems more relevant than ever,” as the lines between craft and art are blurring once again. “Craft media are now represented by art galleries, so the idea of a 50th-anniversary exhibition and book [published by the Monacelli Press and R & Company], and a resoundingly American project, was very appealing, as it was back then,” he says. (The gallery chose 1970, the year the original book was released, as its 50th-anniversary jumping-off point.) The current group of artists includes well-known names like Daniel Arsham, David Wiseman, Nancy Lorenz, Adam Silverman, Jeff Zimmerman, the Haas Brothers, Rogan Gregory, Dana Barnes, and Tanya Aguiñiga, as well as up-and-coming ones like Katie Stout, Misha Kahn, Tiff Massey, Green River Project LLC, John Souter, Woody De Othello, and Joyce Lin, who, at 26, is the youngest member of the group.

“Objects: USA 2020” is curated by Glenn Adamson, who also wrote the main essay for the book; James Zemaitis, the gallery’s director of museum relations, who wrote an essay that unpacks the 1969 show; Abby Bangser, the founder and creative director of the art and design fair Object & Thing; and Snyderman. Adamson and Zemaitis chose the historical objects, while Snyderman and Bangser joined them in choosing the contemporary pieces.

In his essay, Adamson notes that while the original exhibition’s “enthusiastic mixture of functional objects and abstract sculpture, of the novel and traditional, of high modernism and low Funk, feels utterly contemporary,” the digital revolution, with its dematerialization of everyday life, did not exist in 1969, and our awareness of the effects of overconsumption on the environment was less acute. But the contemporary artists that Adamson and the other curators gathered, he says, “work intensely with materials, though not necessarily in the manner of 50 years ago; they think deeply about the space their objects take up in the world.” Adamson also points out that while most of the artists in the 1969 group focused on a single material, “mixed media is the order of the day” for many of the current artists. And craft, he adds, “is no longer treated as a separate field; rather, it has come to be seen as a competency that can be applied to any creative endeavor.”

This is a result of factors like the rise of digital design and fabrication, and the limited-edition Design Art model of the late 1990s and early 2000s, which, Adamson said in a recent interview, “made ambitious objects possible, because of up-front investment; you couldn’t make just one.” He adds that artists like Stout and Kahn “look at that model, but their strategies are much more digital-influenced. One of the distinguishing features is a multiform, flexible approach. There’s no manifesto behind it; in some ways, it’s very liberating.” And while much of this generation has what he calls a “swipe aesthetic,” Adamson writes that, “whatever they make, they make with total determination. They are all in. This is the flip side of their browserlike relationship to content,” adding that “this sense of conviction is a strong point of connection” between the work in the original show and that of today’s.

That sense of conviction certainly characterizes the work of the two youngest artists in the original exhibition. Oka Doner, who is now known for her nature-inspired objects and installations in bronze, wax, ceramics, and other media, was a graduate student at the University of Michigan when Nordness saw her ceramics. “I was the only woman in the program,” she recalls. “I was doing dolls at the time,” some of which, with their tattoo-like impressions, were chosen for “Objects: USA.” Of her approach, Oka Doner says, “It was organic, fragmented—what washed up on the beach… I’m not engaged in a dialogue about materials but about process, the cycle of life.” Nordness, who wanted Oka Doner to make more dolls, offered her a show in New York, the artist recalled. She declined. “I didn’t want to allow the market to dictate what I was going to be,” she says.

Marquis started studying ceramics at the University of California, Berkeley, at age 18, working with both Voulkos and Nagle, but then switched to glass. Frustrated by American glassmaking in general and the program’s limitations, he later received a Fulbright and went to Venice, where he worked at the Venini factory, with its far larger palette of glass colors. There he learned to make the murrine, or mosaic glass, that is a hallmark of his work. “It was like free play,” he said of the pieces he made there, which include Stars and Stripes Acid Capsule. The term “acid capsule” certainly evoked the times. As Marquis adds, “It was Berkeley in the ’60s; a lot of time was spent protesting.” The exhibition opened while Marquis was in Venice, but, he says, “just being in a show with people like Ron Nagle was enough to fill my heart.”

And, as Adamson writes, the current artists in “Objects: USA 2020” have strong convictions of their own, even if their aesthetics are shaped by our fragmented world. Stout’s pieces are colorful and playful, yet often convey a sharply feminist message. Massey’s work addresses themes like African-American body ornamentation. Green River Project LLC’s sculptural approach to wood furniture is akin to that of J.B. Blunk, who was included in the original iteration. Robert Arneson’s California Funk aesthetic influences the ceramics of De Othello and Souter (whose work also incorporates unexpected materials). And Lin, who did a dual degree program—majoring in geology and biology at Brown, and furniture design at RISD—creates furniture that expresses the complexities and anxieties of the Anthropocene. Although the expression might look radically different, the work of these artists makes it clear that today, craft is not just alive, but thriving.