By Julie Baumgardner

There’s lots of discourse at present about the big, behemoth institutions needing to change, adapt and confront their checkered pasts. Today, the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its latest installation, “Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room.” Could this curatorial undertaking—and investment—be a signal or redirect in the house of art?

The new period room is a visual exploration of “the boundaries of what period room can be, acknowledges the fiction of every period room and embraces it as a reconstructive historical interpretative act,” explains curator in charge of the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Sarah Lawrence. “With that as a starting point, it would allow us to tell the stories of period rooms otherwise omitted from what we have in place.”

Period Rooms are a tradition that stems from white European aristocratic convention but they also are inherently a work of fiction. As Ian Alteveer, curator of contemporary art at the Met who also collaborated on the project, explains, “The artifice of the period room is the idea that you can quite enter but you project yourself into the space as a viewer.” The rooms ask, as he says, “‘Who lives here? Do I live here? Who do I have to be to live here?’”

Visitors to the Met are accustomed to peering into the domestic spaces of rich, white people, perhaps a French monarch or an American robber baron. Instead, “Before Yesterday We Could Fly” presents a space for a Black matriarch from Seneca Village. Despite historical attempts to slander it otherwise, Seneca Village was a thriving middle-class Black-owned, integrated neighborhood, ultimately razed by the City of New York to make way for Central Park. Located at what is now West 82nd to 89th Streets, its property lines ended about 200 yards away from where the Met currently sits.

Lawrence explains that the curators “felt strongly that the Met has an opportunity and responsibility by proximity,” to Seneca Village to engage with the horrors of history. Here was a chance of “imagining if the Seneca community had continued to thrive in its place, with a resident who still lives in a historical house, what would she be in that space and then retaining the 19th century character and extending it into the future” she says. “There’s this collapse between past/present/future and a notion of diasporic time, which is itself a critique of the period room.”

That imagining led to a fascinating structural outcome as much as it offered the second part of this “new mode” for the Met, as well. Both white, Lawrence and Alteveer stress that the opportunity, which centers the Black experience, “isn’t our story to tell,” and so they called upon “Black Panther” production designer Hannah Beachler as the artistic lead on the project. Though the curators thought it might be a moonshot, Beachler felt the opposite and told Lawrence she’d been thinking about the concept prior to being approached. “Hannah knew what the potential was, and it led us in directions we hadn’t anticipated, which is very much her vision,” adds Lawrence.

Part of the exhibition-building process was to host a “convening,” where filmmakers, writers, designers and scholars, including consulting curator Dr. Michelle Commander and Seneca Village archaeologist Cynthia Copeland, were brought together to exchange ideas and discuss how this project should be produced and unveiled. But it wasn’t just consulting outside voices who were integrally involved. “It was a really special mechanism of our project,” says Alteveer. “For the first time, we convened colleagues around our museum. This was inspired by our colleague in our education department, Suhaly Bautista-Carolina, and that prompted us to say, which we rarely do, ‘let’s include input from staff.’”

This community-oriented participation marks a signal shift within the institution. As Lawrence says, “The idea was: let’s propose a different model.”

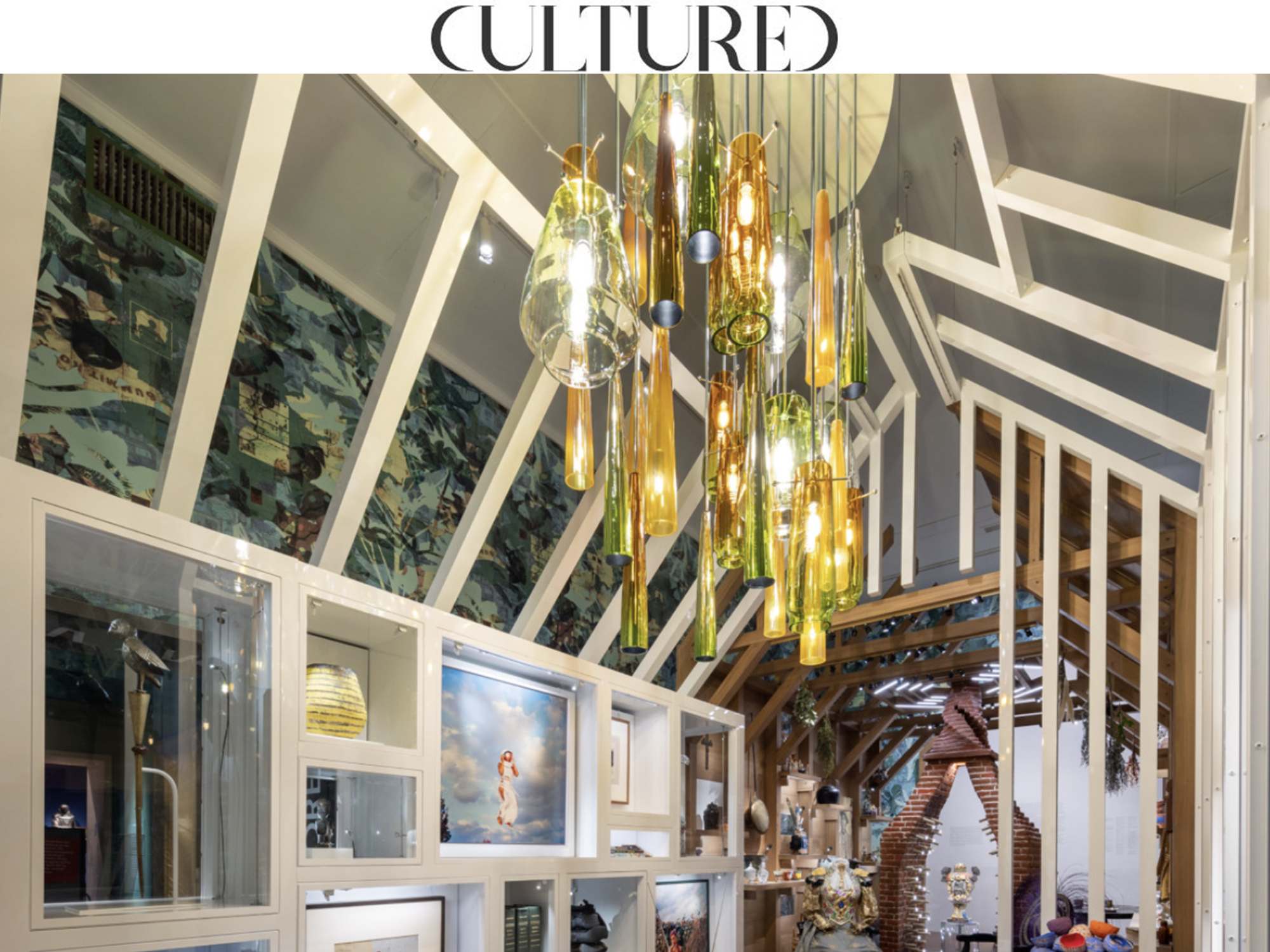

The exhibit itself presents a 19th-century house turned open plan with a contemporary extension and filled with both historical and contemporary art and objects. “From the future, you can look back into the past, and from the past look into the future,” says Alteveer.

The house is decorated with period pottery by free African American Thomas W. Commeraw and other objects that would have been found in Seneca Village, alongside contemporary ceramics by Roberto Lugo (including a gorgeous centerpiece inside the French chimney). A chandelier by Nigerian American designer Ini Archibong hangs inside and the project sought guidance from South Africa’s Southern Guild gallery, which provided seating by Atang Tshikare and Chuma Maweni.

In addition, the Met commissioned four artists to create new works for the exhibition. Njideka Akunyili Crosby created a wallpaper that is a layered patchwork of Black diasporic cultural artifacts, including the map of Seneca Village. Jenn Nkiru’s video piece sits in the extension almost like a television (one can’t help but think of Gil Scott-Heron’s anthem, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”). Fabiola Jean-Louis designed a dress of paper gilded with gold, in the style of mid-19th-century formal wear, both a reference to the European women of period rooms and the Seneca Village matriarch. And illustrator John Jennings created an Afrofuturist graphic novella about the room to be published in the museum’s Bulletin, as one cannot discuss Afrofuturism without Octavia Butler’s speculative world-building or comic books.

The period room, which will be open for two years, is both a proposal for the museum to rethink its own internal practices, as well as a new proposition for curatorial impact. “This room is very accessible,” says Lawrence. “I’m hoping there’s an experiential punch to that recognition even if it’s not fully articulated, our visitors might go back to our other period rooms and think more critically.” For those who may remain skeptical that this occasion is a foreshadowing of true structural change, take a look at other large institutions and how they’re handling their approaches to producing equitable and engaging exhibitions.