By Julie K. Hanus

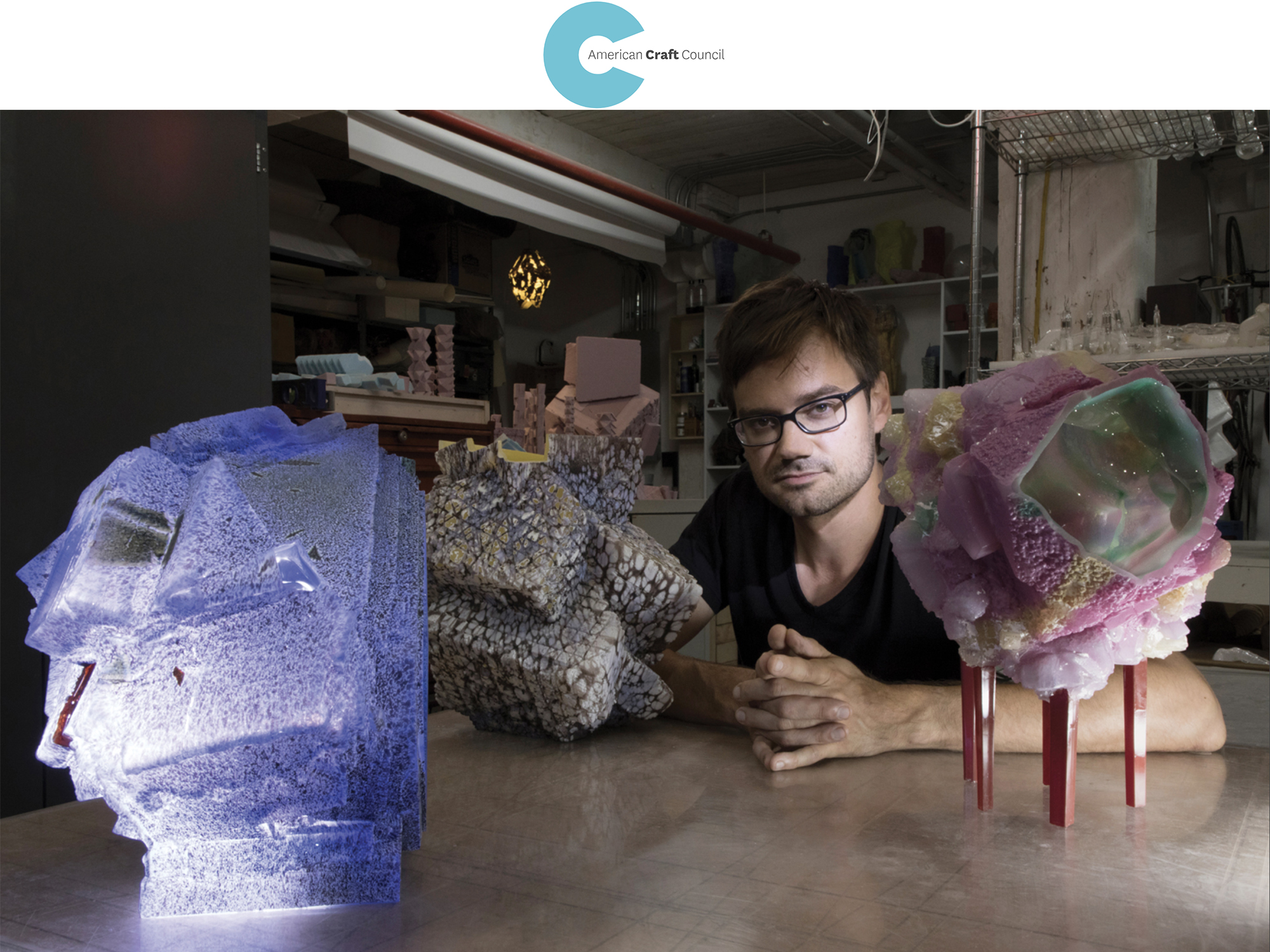

Thaddeus Wolfe is not your typical glass artist. For one thing, he doesn’t spend much time blowing glass. “Even when I’m working intensely, making a lot of pieces, it’s like two days a month,” the 38-year-old says. And the method he’s known for – a time-consuming process of creating Styrofoam positives and casting them to create glassblowing molds, which ultimately must be broken to reveal (and cold-work) the object within? “I didn’t invent this technique,” he points out.

At the same time, it’s also part of what makes Wolfe’s work special, says Susie J. Silbert, curator of modern and contemporary glass at the Corning Museum of Glass. “At this time, when artists in traditional materials are pushing into new media and installation art, and expanding their practice that way, Thaddeus is taking this very traditional technique – glassblowing and moldblowing, which has existed since the Roman Empire – and is using it to make something that is unlike anything I’ve seen in glass before.”

Wolfe’s work is simply different. It is the product of precision but also improvisation, of ancient technique but also contemporary innovation. And 10 years after he began making his moldblown Assemblage series, Wolfe seems to be just now hitting his stride. “Some artists really have a clear ending point or concept before they even start, and some people, like me, work more intuitively,” he says cheerfully. “I learn by doing. And it makes it a bit of a slower process to get to the final result.”

Wolfe was born and raised in Toledo, Ohio, birthplace of the American studio glass movement. It’s tempting to imagine that glass, then, was his destiny – but that’s another yes-and-no answer. “I think maybe growing up in Toledo did give me the idea that I wanted to try it,” Wolfe offers, undoubtedly having been asked this before. What he did know was that art was his path.

In 1997, Wolfe enrolled at the Cleveland Institute of Art, intending to study painting. During his second year of foundation courses, spanning painting, sculpture, drawing, and design, he took glass as an elective. The physicality and teamwork of the medium drew him in, as did the dedication required to master the skills. But perhaps most of all, glass seemed to offer opportunity: a less crowded field for someone interested in charting his own course.

After graduation, Wolfe moved to New York. A crucible for many young artists, the city also extracts a toll. But along with financial struggles, there were positives – and progress. In recounting those early years, during which he played with sculpture before moving on to experiment with vessels and lamp designs, Wolfe points to the generosity and influence of others. Michiko Sakano, a former professor, let him take care of her studio in exchange for time to blow glass on Monday nights. Eventually, he started working for Jeff Zimmerman, whom he credits with teaching him how to avoid overthinking the medium, how to let mistakes guide the process. In 2006, he began working a few days a week for Josiah McElheny, whose respect for his assistants is something Wolfe admires and emulates to this day.

Wolfe made his first moldblown pieces in 2007, during a winter residency at WheatonArts in New Jersey. His earliest Assemblages were solid black objects, with some surfaces ground to a near-mirror finish. Compelled by the technique but not wholly satisfied with the results, Wolfe boxed them up and stashed them in his apartment when he returned to the city.

Had he stored them somewhere else, had he not hung on to them at all, who knows what work Wolfe would be making today? But about a year and a half later, the proto- Assemblages caught the eye of Jamie Gray, of the design shop Matter. “That was the beginning,” Wolfe recalls. While he had never lost interest in his moldblown pieces, the expense of renting a glass studio to blow them had held him back. “[Jamie] gave me the push to really try it.”

Wolfe took the leap. Experimenting with ways to infuse more color into the process, he created five new Assemblage pieces for Gray’s store. In a typical story, this might be the moment where the artist rockets to stardom, turns a corner in his career. “It took a really long time,” Wolfe recalls. “Nobody wanted them at first.”

“But,” he adds in his amiable, laid-back way, “it always takes a while.”

That slow burn, the ability to see the long game even when the progression isn’t linear, seems to be a kind of Wolfe signature. It’s reflected even in the way he makes each object, investing in its creation. His work is a reminder that art is as much about endurance as inspiration.

Each of Wolfe’s pieces starts with a Styrofoam positive. At first, the material was a practical choice. Clay, his original modeling medium, didn’t offer the planar surfaces he was looking for. Abundant, accessible Styrofoam, on the other hand, allowed him to create angular, crystalline constructions with the tiniest of nooks and crannies.

Over time, his modeling has evolved. Lightweight Styrofoam is easy to manipulate and eventually helped him increase the scale of the work, Wolfe says. Today, it’s not uncommon for him to have four or five positives going in his studio, as he cuts, carves, and reassembles them in a meticulous yet improvisational pursuit of form. “I spend a lot of time constructing them and then just thinking about them as they are,” he says. He sketches to record ideas of what to make – but those sketches often bear little resemblance to the finished works.

“I have to figure out what I want by doing it,” Wolfe says. “Figure it out through making.”

Recently, Wolfe has begun using color bars – thin rods of pigmented glass, which most artists roll onto a molten base – to draw directly on the surface of the glass before blowing it into the mold. “I’m trying to use the color more as paint,” he explains. The effect is nearly encaustic, a matte saturation rarely coaxed from the material. The pieces cool for four days in a kiln, after which Wolfe might grind away surface colors, polish parts, or cut openings. The result is sculpture that looks like no other – and certainly not like glass. “I think that’s what is surprising and appealing to people,” Wolfe says.

Silbert remembers that off balance feeling when she first saw his work in person in 2013. At the time, she was a freelance curator, and Wolfe was in his first group show at R & Co., the New York gallery that today is his primary dealer. She found herself fascinated by the way Wolfe uses color and transforms an art form that is concentric into something so angular: “It is impressive and quixotic – and attention demanding.”

In early 2016, Silbert began her tenure at Corning and later that year chose Wolfe for her first – and the museum’s 31st – Rakow Commission. The annual prize supports the development of a new work by an artist not yet in the collection. As Silbert explains, it’s about building the collection, but it’s just as much about investing in the future of glass, “and I see Thaddeus as an important person in building that future.” For Wolfe, the commission was a welcome opportunity to further develop his work. His Stacked Grid Structure is his first Assemblage with bronze inclusions, protruding like tiny stilts or scaffolding. “It’s moving further from the vessel,” he says, “and more into an experimental architecture of form.”

He pushed further down this path this summer with a solo show at Pierre Marie Giraud in Brussels. A half-dozen of his newest sculptures perch on tiny bronze supports – familiar and alien, ancient and futuristic all at once. They’re perplexingly attractive – demanding attention, as Silbert says. “There are parts of them that I really like,” Wolfe says, which – however it sounds – is high praise.

“I’m never really 100 percent satisfied,” Wolfe explains, embracing contradiction at his core. However planned, however polished, no piece is ever quite complete. Instead, each is a stepping-stone to the next – an opportunity to revisit, revise, and evolve.