By Rebecca Sherman

A DALLAS NATIVE, HIS WORK BLURS THE LINES BETWEEN ART AND FURNITURE, FANTASY AND REALITY. A RETROSPECTIVE AT THE MUSEUM OF ARTS AND DESIGN IN NEW YORK SPOTLIGHTS CHRIS SCHANCK’S TALENT FOR TRANSFORMING MUNDANE MATERIALS INTO LAVISH OBJECTS LAYERED WITH PERSONAL MEANING. IN A REVEALING INTERVIEW, HE SHARES HIS ROAD TO ADDICTION RECOVERY — AND HOW ART SAVED HIM.

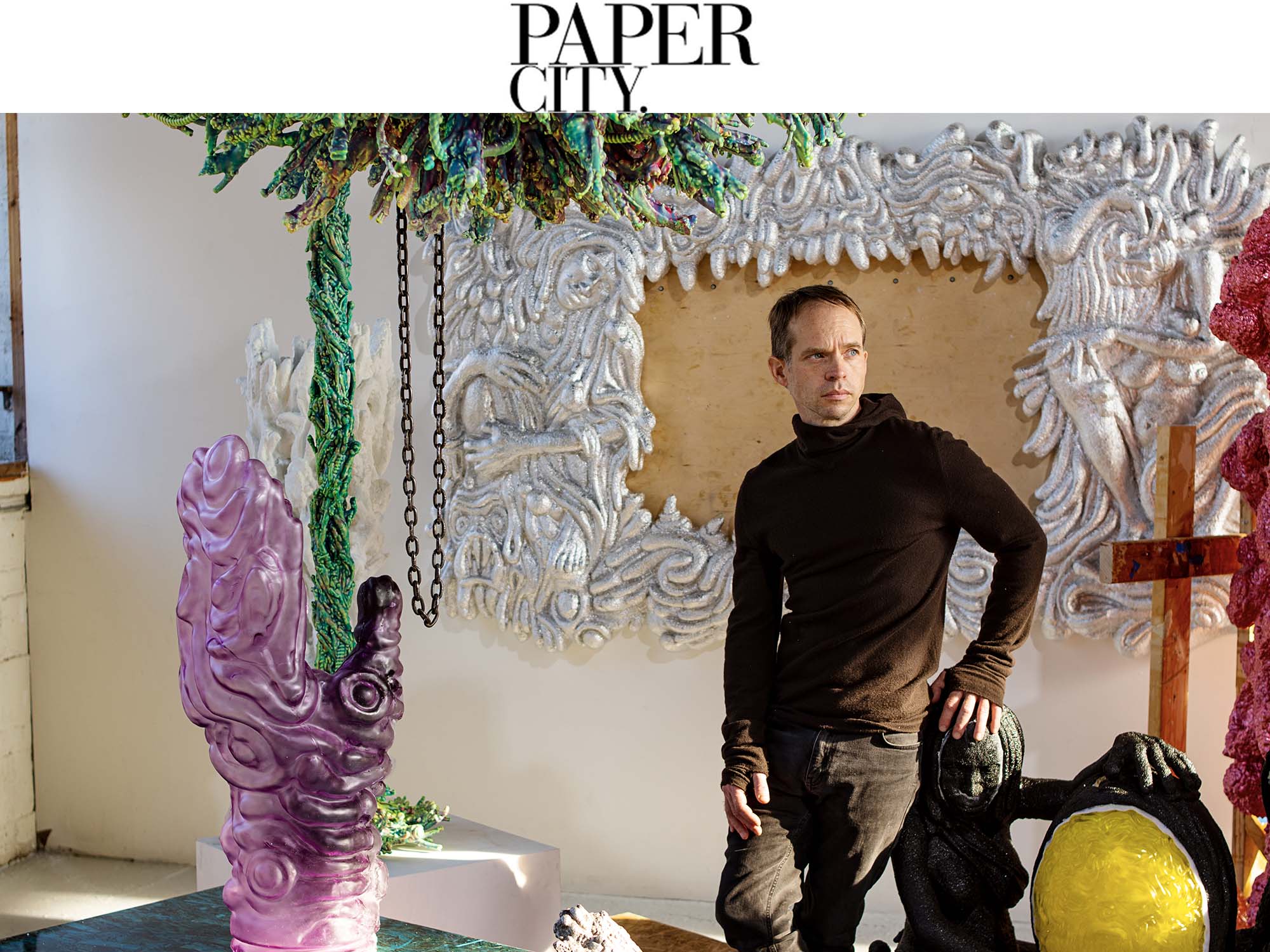

Is it furniture or art? Chris Schanck gets asked that a lot, and the answer is a bit of both. “In my heart I’m an artist — designing furniture is how I’ve found my way,” he says. Schanck, 47, toils in the netherworld where art and design converge, his work assembled from found materials and covered in shimmering resin and aluminum foil. A Dallas native now living in Detroit, Schanck studied painting and sculpture in the 1990s at Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, which he credits as a sanctuary for art amid a home life roiled with addiction and instability. Now an international star in the world of contemporary design, the artist’s furniture is highly sought after, ranging between $30,000 and $150,000. Designer William Sofield furnished the Tom Ford flagship on Madison Avenue with a chair and console, and architect Peter Marino commissioned Schanck to create benches for a dozen Dior boutiques. Bottega Veneta installed several of Schanck’s pieces at a Detroit popup shop, and his works are held in private and public collections around the country, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Dallas Museum of Art.

The Museum of Arts and Design (MAD) in New York has mounted a retrospective of his work, “Chris Schanck: Off-World” (through January 8, 2023), supported by Friedman Benda, the elite New York gallery that also represents Schanck’s work stateside. “Chris is one of the most exciting artists working in contemporary furniture today,” says the show’s guest curator, Andrew Blauvelt, director of Cranbrook Art Museum, which owns two of Schanck’s works. “As an artist, he adopts a conceptually rich approach to his work, and as a designer he pushes expectations of what furniture can be.”

Twenty-four of his elaborately carved and colorful furniture forms are featured, including Mum, a chandelier made in collaboration with his mother, with whom he once had a strained relationship. “I wanted to make peace with her, to reconnect in some way,” Schanck says. His mother sculpted the chandelier from twigs and sticks collected from vacant lots and the beach near her Florida home; Schanck organized it with an armature of steel pipes, applied color through layers of tinted resin, and made it into a working lamp. Shuddering Cabinet — a tall chest of drawers that looks as if it’s being devoured by pink foam — has drawers and cabinets made from OSB (oriented strand board), an inexpensive plywood-like material ubiquitous throughout Detroit’s poorest areas, and often used to board up foreclosed or abandoned buildings, especially in the Banglatown neighborhood of immigrants where Schanck has lived and worked for a decade.

Alley Vanity was inspired by the late-19th-century Martelé dressing table in the Dallas Museum of Art’s collection and debuted at the DMA in “Curbed Vanity” in 2021, his first museum solo show. Made of found objects from his Detroit neighborhood, the dressing table is coated in resin and aluminum foil, a reference to the Dallas-area aluminum factory where Schanck’s father worked. Chronically unemployed, his father moved the family a dozen times before landing work at the factory, Schanck says. He and his brother also worked there for a time. “Aluminum foil is more than just a material, in the sense that it represents our family’s first taste of stability,” he says. The retrospective also includes the artist’s newest figurative creations, including Eye of the Little God, a bas-relief mirror inspired by Sylvia Plath’s poem “Mirror.”Schanck came across the poem — a meditation on aging and the end of life — while researching the history of mirrors for the Alley Vanity piece.

His works might be unconventional, but Schanck can design and build furniture with the best of them — he has a Master’s of Fine Arts in design from Cranbrook Academy of Art, which produced legends Charles and Ray Eames, Harry Bertoia, and Florence Knoll. Prior, he trained at New York’s School of Visual Arts, where he earned a BFA in sculpture — an opportunity he almost scuttled while still at Booker T, when a recruiter offered him a full scholarship that he initially turned down. “I was dealing with some hardcore addictions and depression, flirting with suicide,” Schanck says. One day, he put a pistol to his head, not knowing if it was loaded or not. “What crossed my mind at that moment was: ‘Well, you could end it all, or you could give it all to your work and see what happens,” he says. He put the pistol down. “I dug up the recruiter’s card — the deadline for college had already passed — and I pleaded with him to give me another chance.” He did, along with a full ride to the college.

Later at Cranbrook, Schanck thrived under the school’s “thinking through making” focus on studio work and experimentation, where he was introduced to the institution’s legacy of radical, avant-garde furniture design. Rigorous group critiques taught him to think critically about his own work, and the inherent boundaries that designing furniture presented were liberating. “It gave me freedom to dig as deep as I wanted within that space and explore it,” he says. After Cranbrook, Schanck toyed with the idea of becoming an industrial designer “who made useful things … But my natural instincts kicked in, and the sculptor in me came back.” He’s never strayed far from the practical, though, so making complex sculptures that are also furniture has advantages. “It’s familiar, and people can relate to the work, which isn’t always the case with art,” he says. “I can bring somebody over to the Mum chandelier and say, ‘What are we looking at? Are we looking at a sofa? Are we looking at a mirror?’ We’re obviously looking at a light, and everybody’s on the same page, no matter how bizarre it is or what I’m intending with the narrative. It’s an entry point that can ease people into it.”

Schanck works out of a studio in a converted 1920s machine shop in Banglatown, employing artists, students, and craftspeople from the neighborhood, which is mostly populated by immigrants. His art is expensive — the prices reflect intense production costs and a living wage paid for seven people, including himself — so he’s looking for ways to make other art that’s affordable. He’s in the early stages of a collaboration with a friend, Detroit artist Wesley Taylor, that might involve limited-edition clothing and music, which they’ll kick off at a low-key underground show in New York that circumvents the commercial art world. Most recently, he’s joined the roster at the prestigious David Gill Gallery in London — which represents the Campana Brothers, the late Dame Zaha Hadid, and Daniel Libeskind — and is feverishly working on pieces for a Fall 2023 solo show.

The significance of making a big mark in the rarefied world of art and design isn’t lost on Schanck, who started out with all the chips stacked against him. “I’m not the kind of person who’s supposed to make it in this world,” he says. “Art is like love — it’s a total leap of faith. It can crumble under your feet, or it can sustain you.” madmuseum.org.