By Kathleen Langjah

A revelatory presentation of the experimental designer Gaetano Pesce is on view at Friedman Benda through December 14. Titled Age of Contaminations, the carefully selected historical sweep provides a close reading of the idiosyncratic designer’s practice over 27 crucial years of his career, beginning with the asymmetrical, modular Yeti Armchairs (1968) and concluding with the otherworldly Ghost Lamps (1995), where recycled paper and polyurethane has been molded into a vaguely figural silhouette. Referencing an early peak of Pesce’s career, the title Age of Contaminations is borrowed from the artist’s installation in The Museum of Modern Art’s historic 1972 exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, where the designer conceived works for a post-apocalyptic future where humans have settled into subterranean cities to escape an unidentified fallout on the surface. The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated e-catalog available for free on the gallery’s website, wherein leading authority on craft and design history Glenn Adamson provides a chronological survey and impassioned critique of Pesce’s career.

Perhaps the most interesting designs on view are the least aesthetically pleasing: Dacron-filled fiberglass cloth chairs— Golgotha (1972)—resemble the functional version of a Piero Manzoni painting, and the garish, slick palette of his Golgotha Table (1972) provides a visually grating yet conceptually transcendent testament to Pesce’s Roman Catholic upbringing. The designer’s relentless openness to experimentation and earnest resistance to a consistent style is manifest in one of the more striking works in the exhibition is the monumental Moloch Lamp (1971), deftly placed behind one of the gallery space’s pillars, allowing it to make an even more powerful impact once visitors are confronted with it in closer proximity. Pesce’s most famous design, the Up5 (Donna) chair and Up6 footstool make a requisite appearance just beneath the lamp’s intense metallic glow. The chair, which resembles the breasts or buttocks of the female body, is tethered to its spherical footstool, mimicking a prisoner’s ball and chain. A recent demonstration by the feminist group Non Una Di Meno during Milan design week expressed explicit opposition to the design, yet Pesce insists that the work was intended to emphasize the restrictions of femininity in order to spur debate, rather than uphold traditional values pertaining to gender.

While Pesce’s designs clearly coincide with the major evolutions in 20th century art—Germano Celant has identified the designer as an affiliate of the Arte Povera movement that dominated avant-garde circles throughout Italy in the 1960s and ’70s—he has consistently embraced materials and practices that blur the distinctions separating genre and discipline. Indeed, as Adamson notes in his essay, it is the material expression of Pesce’s sincere belief in the potential for art to change the way one sees the world that constitutes the most contiguous through-line of his oeuvre. Although the exhibition reveals that only a few patrons and collectors have been adventurous enough to live with his designs, the designer’s drive to imbue his objects with a unique mixture of pathos and material innovation is apparent in each work in the exhibition. As Celant observed in his 1990 survey of modern Italian design, Pesce’s works seek to “give form to the form of life.”

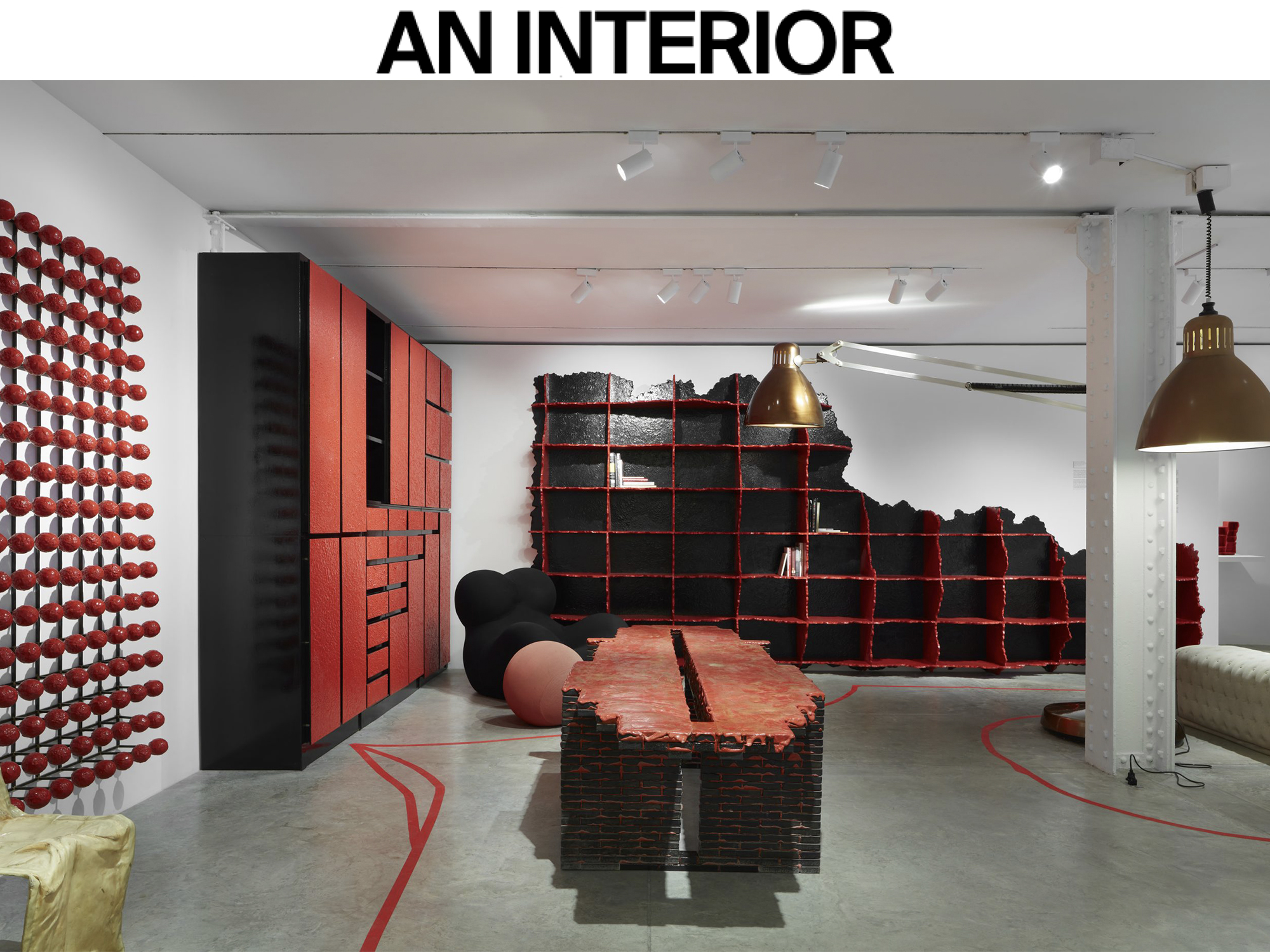

Never one to hang up his tools and retire, Pesce is making waves on the New York art and design scene at the moment. Coinciding with the Friedman Benda show, the revered talent has also moved a large part of his studio into Salon 94’s new 86th street gallery space for a unique exhibition. Visitors are able to witness the artist in action; pouring resin and producing new work. Workingallery runs through to the end of this week.