By Glenn Adamson, Co-Curator, Postmodernism

Of all movements in art and design history, postmodernism is perhaps the most controversial. As a phenomenon it defies definition, but it is a perfect subject for an exhibition. Postmodernism was visually thrilling, a multifaceted style that ranged from the colourful to the ruinous, the ludicrous to the luxurious. What it always maintained was a drastic departure from modernism’s utopian visions, which had been based on clarity and simplicity. The modernists wanted to open a window onto a new world. Postmodernism, by contrast, was more like a broken mirror, a reflecting surface made of many fragments. Its key principles were complexity and contradiction. It was meant to resist authority, yet over the course of two decades, from about 1970 to 1990, it became enmeshed in the very circuits of money and influence that it had initially sought to dismantle.

Our exhibition falls into three broad sections, each of which looks at a stage of postmodernism’s passage from a fringe radical style to the dominant visual language of 1980s corporate culture.

The first section examines the exploration of the past, and of cultural difference, by architects and designers in the 1960s and 1970s. The sources of inspiration at this moment were broad: Ettore Sottsass, perhaps Italy’s most prominent designer, travelled to India and California and took equal inspiration from mysticism and pop culture. The exhibition’s first room features two ceramic ‘totems,’ fanciful objects that were not really fucntional, but which Sottsass suggested might be useful for storing contraceptive pills or halluciongenic drugs. This displacement of the designer’s job description into the counter-cultural imagination was outsized in its influence. The same could be said of the ‘research’ conducted by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown in Las Vegas in the late 1960s. Embracing pop vernacular and the logic of the ‘Strip’ with cheerful exuberance, they helped inspire a whole generation of architects to look away from modernist strictures and embrace the possibilities of contextualism and communication.

In the 1970s, postmodernism acquired its name. It was bestowed by the theorist and architect Charles Jencks, whose 1977 book The Language of Post-Modern Architecture put the term on the critical map. Though he is mainly known for his many writings, we reproduce a building by Jencks at full scale in the exhibition: the Garagia Rotunda, an inexpensive but wildly inventive house that he built for himself in Cape Cod. It was built entirely from store-bought millwork, using as its core a pre-fab garage. The exhibition also features another major reconstruction: Hans Hollein’s fa9ade for the Venice Biennale in 1980, which had as its centrepiece a ‘street of styles’ named the Strada Novissima. Hollein designed a set of columns that reprise the history of architecture, from the primitive garden through classical ruin to a modernist skyscraper. This extraordinary set piece is again recreated in the V&A exhibition at full scale.

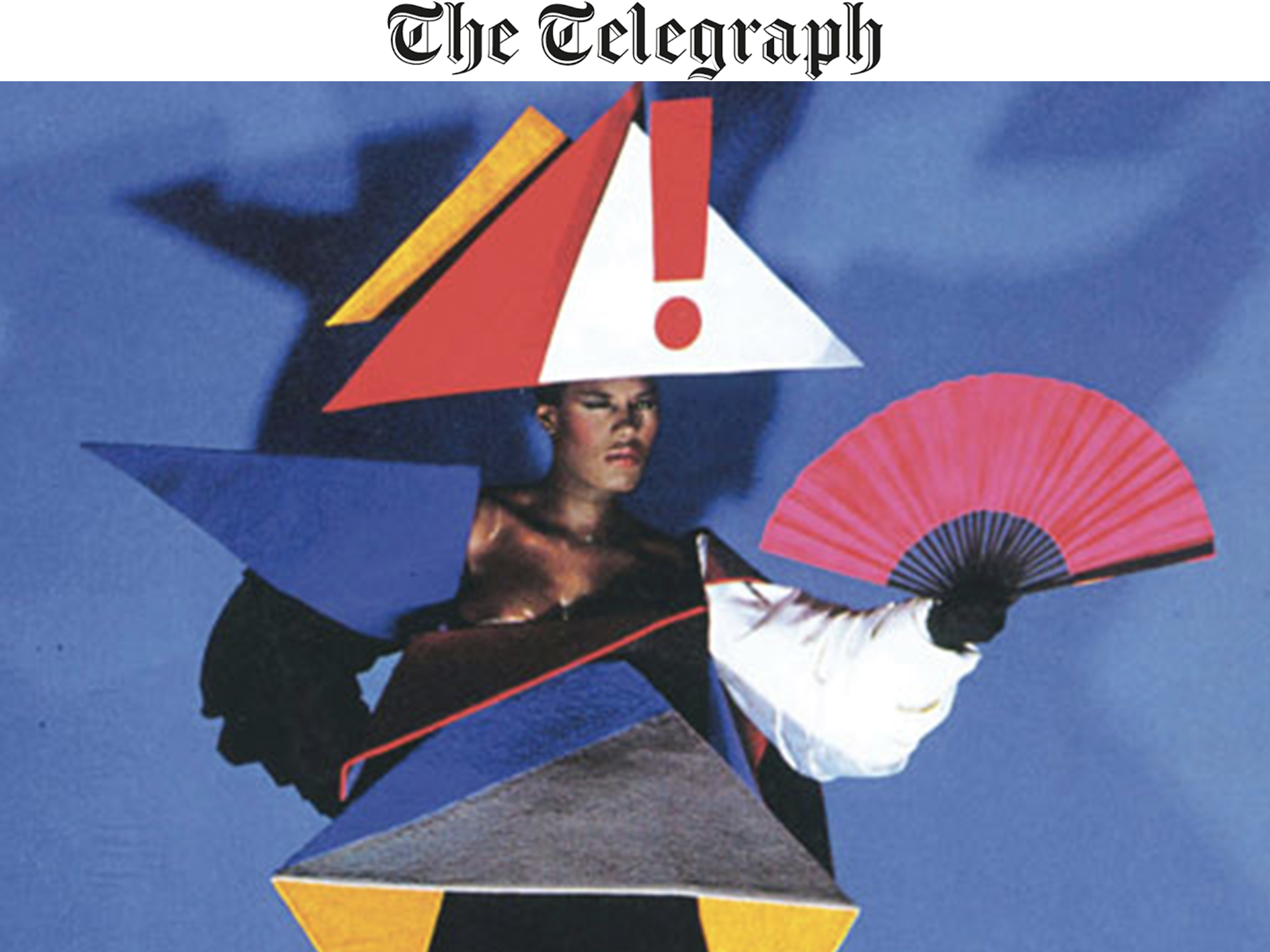

As the 1980s approached, postmodernism went into high gear, and our second section examines the inception of what came to be known as the ‘designer decade’. Vivid colour, theatricality and exaggeration: everything was a style statement. Whether surfaces were glossy, faked or deliberately distressed, they reflected the desire to combine subversive statements with commercial appeal. The most important delivery systems for this new phase in postmodernism were magazines and music. The work of Italian designers – especially the groups Studio Alchymia and Memphis – travelled round the world through publications like Demus. Meanwhile, the energy of post-punk subculture was broadcast far and wide through music videos and cutting-edge graphics.

Finally, our last section ‘Money’ examines the rise of corporate postmodernism and the reflection of artists and designers on the commodity status of their own work. As the ’80s wore on and the world economy boomed, postmodernism became the preferred style of consumerism and corporate culture. Japan entered the years of the so-called ‘bubble economy,’ allowing architects such as Philippe Starck to realise trophy-like buildings. In Europe and America, ‘design editing’ firms like Alessi and Swid Powell turned the name brand value of architects to the selling of luxury silver and designer tableware.

Ultimately this moment of commercialisation was the undoing of postmodernism; it collapsed under the weight of its own success. Yet looking back, we can learn a lot from postmodernism’s fatal encounter with money. Today, when the marketplace has again had its way with us, it is useful to ask: do we still live in a postmodern era? Yes and no. It’s best perhaps to think of postmodernism as a warning system, alerting us well in advance to the dynamics of the 21st century. In the permissive, fluid and hyper-commodified situation of today, we have a lot to learn from these provocative, uncertain objects.