By Emma Crichton-Miller

RAPHAEL NAVOT IS determinedly not an industrial designer. Instead, he reinterprets, from a distinct, 21st century perspective, a decorative arts tradition rooted in skilled hand-craftsmanship and fine materials. Drawn to organic shapes and colours, with contrasting raw and refined textures, his inspiration is mainly derived from nature and the materials themselves.

Born in 1977 in Jerusalem, Navot graduated from the Design Academy Eindhoven with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Conceptual Design in 2003. He founded his own design and interior architecture studio in Paris. Among notable projects are David Lynch’s Paris Club Silencio (2011), the design of Hotel National des Arts et Métiers in Paris (2017), and the library and art gallery at the Domaine des Etangs estate in Massignac, France (2018). Navot has collaborated with brands such as Alessi, Cappellini, Venini, and Roche Bobois for which he won the 2020 ELLE DECO International Design award.

The Design Edit spoke to him as he opened ‘Raphael Navot: On the Same Subject’, his first solo exhibition at Friedman Benda Gallery in New York.

Emma Crichton-Miller: This is your first solo show at the gallery (Friedman Benda). I am curious to know how this project emerged?

Raphael Navot: My collaboration started four years ago, when I was working on more commission-based pieces. This project is so different – there’s no client, no specific budget, no context – and it made me realise that as designers we are normally associated with service. We do furniture, we do restaurants, we do hospitality projects, we are partly an ‘artist-at-service’. This project, by contrast, was quite free. Suddenly there were no boundaries. Working on a solo show, it was interesting for me to stop for a second and to choose to focus on one subject.

Normally in a design process there is an evolution. You work towards something and all the designs that were happening on the way die out, and only one wins: the one that answers the brief best. But for this exhibition I could have several winners. There was no linear process. So I started on a project, came up with several designs and then I went back to the stem, and started again on another branch. This was a real privilege – to stay for a while and go deeper into one field.

Emma Crichton-Miller: So when you are given freedom to make what you like, what is your overriding motive? What is your ambition in producing an object?

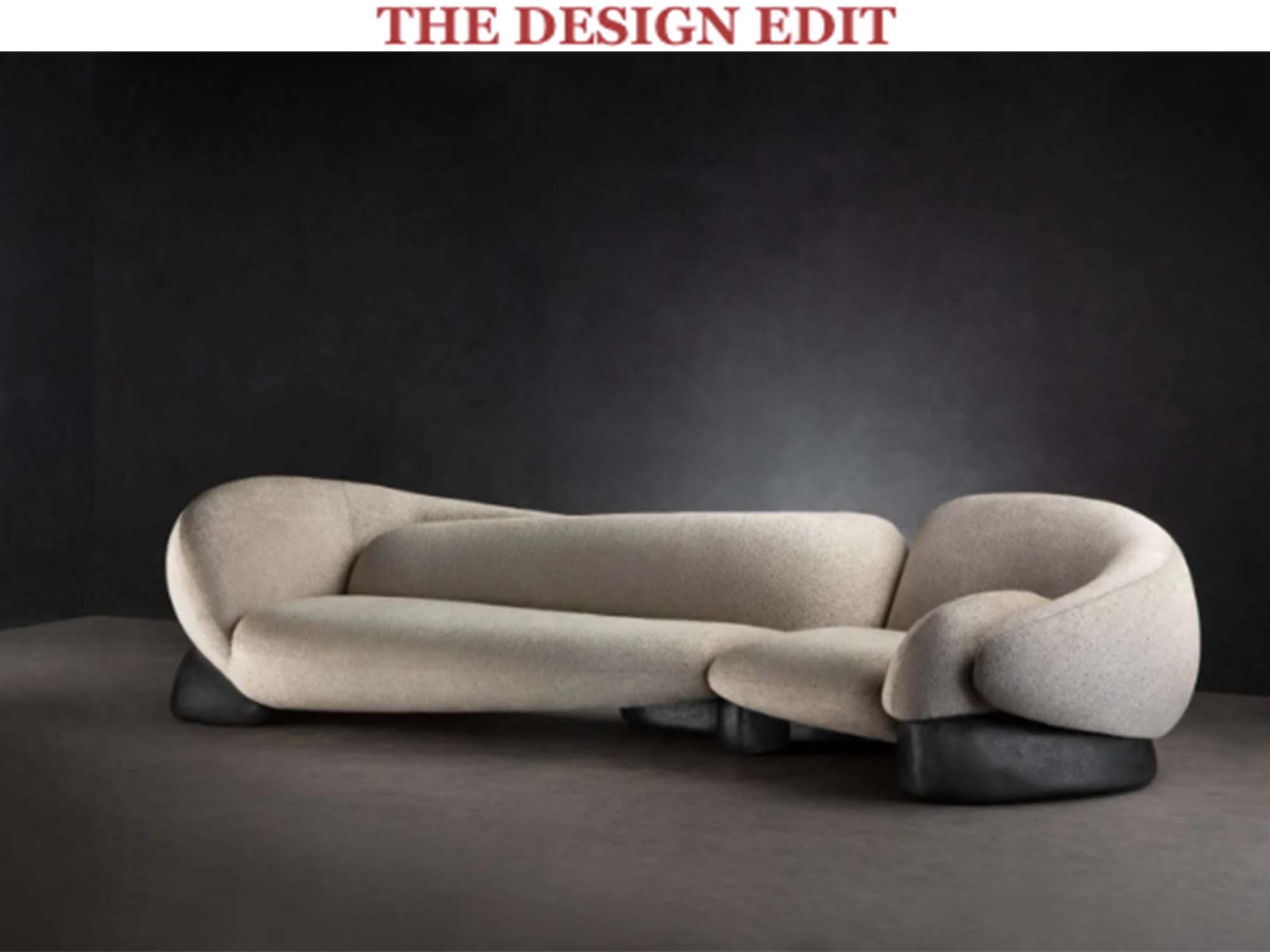

Raphael Navot: My work is definitely corporal. It relates to the body. This is how I see furniture. This is my field. My pieces are not intellectual or academic in design, but they can be in terms of craft, in terms of knowledge, in terms of heritage, transmission and materiality. But I always opt for something that’s somewhat timeless. Our body hasn’t changed for thousands of years, why would anything relating to it? And I love the idea of comfort.

Emma Crichton-Miller: Well I think that’s so important, particularly after the pandemic obviously, but I think now we feel more able to express our need for comfort.

Raphael Navot: Yes, and I would even say ‘mental’ comfort even more. Sometimes when I go round the fairs I’m like “Wow, this world of ours today is very afraid of beauty.” Beauty is natural and it’s in us. But sometimes now it is as if the frontal cortex is winning – everything is so rational. The body is losing in this era. Design is almost a primordial exercise – it really started with choosing a rock to sit on – and that’s why I chose to do these very simple assemblies of volume.

What is furniture but just aligning with our ergonomical needs? I don’t want to lose that. And the more I work with hotels and restaurants and hospitality, the more I learn a lot about all sorts of crafts, and their role in creating beauty and comfort. Why wood? Why these kinds of springs? Why this kind of horsehair, or feathers, or cashmere, or wool, or linen? But this tradition is slowly losing to quick solutions, it’s losing to practicality.

Emma Crichton-Miller: In your work, there is the sense that everything matters. The way that furniture gives to our body, or the way it feels to our hand is as important as what it tells our intellect.

Raphael Navot: I don’t take comfort in nostalgia, but my work is about similar values that I think are eternal. There’s wood, there’s stone, there’s glass, there’s metal. The range is beautiful and it’s really, really sufficient. I’m not on the lookout for the new, the eccentric, for its own sake.

Emma Crichton-Miller: There’s a wide range of materials, however, in this small collection. Were you led by your own instinct for comfort? Or was it led by what people want?

Raphael Navot: I’m not afraid of the principle of service. I think it’s beautiful. It’s where you decide to align your talents to the act of giving. It’s a case of “These are my talents, what can I do for you?” It makes me feel like I belong. I’m not an artist, I’m a designer. There’s a lot of ways, however, to get there and at this specific time, with this show, I pushed the possibilities a bit further than I would normally. For instance, I would normally cast bronze with a traditional foundry, but this time we didn’t. Instead we did 3D printing, which makes the pieces as noble in terms of visual impact and touch, but it’s lighter and it’s using today’s technology.

Emma Crichton-Miller: So you were interested in the chance to experiment with these very high tech processes and materials, but also with these traditional craft technologies.

Raphael Navot: Yes, but not just for the sake of it, but because of the context. I think it is very important nowadays, especially as the whole idea of collectible design/decorative art – or whatever you want to call it – is expanding, and is so confusing – for me to make a piece that is not easy for a manufacturer to create, but is possible for a gallery. So this was the opportunity to say “Alright, that project will be costly, it needs to be made by hand. We can’t do it more than x amount of times, as there is one ebonist who is able to make this desk.”

There was a challenge not only in the forms and the eccentricity of the pieces, but in the actual craft – finding people who could make the pieces. A big part of the show was to search for artisans and specialised processes.

Emma Crichton-Miller: In a sense that is also returning to the great tradition of les arts décoratifs.

Raphael Navot: Oh, it’s incredible. That’s why I live in Paris!

Emma Crichton-Miller: I understand that drawing is fundamental to your practice. I wondered how that operated in this case, whether that’s the way you evolve forms or ideas?

Raphael Navot: First, I’m very technological, I’m a little bit of a computer geek in that sense. So the concept is very digital. I think that drawings help me to step back. Usually I would start with a particular drawing, mostly liquid charcoal, or watercolour, to understand volumes. When you have a knowledge of computer programmes nowadays you can get lost in them quite quickly and lose the physical touch, the corporal understanding of proportion and beauty. So, in order to search for a certain balance, I start with drawings. It’s a bit of an abstract way for me to approach the content, or the intention, or the values that I wish to express. Later on, when I know my values, I can use the software. Drawing helps me to keep a certain type of physical sanity.

Emma Crichton-Miller: Because drawing is a physical act and in a sense your body comes into it …

Raphael Navot: Yes, it’s so different from any screen. And there are errors … These errors can unveil a new path.

Emma Crichton-Miller: I want to look at this fundamental understanding that all our ideas about furniture derive from nature. I wondered about the role of nature in your work?

Raphael Navot: I’m not living in nature. I’m very urban and I like that too. Most of the time I read about nature through geology, biology, ecology or even philosophy. I don’t really consult design magazines. I’m not really knowledgeable about design history. It’s almost about drawing your design ideas directly from the source.

In addition, I come from Jerusalem, which is embedded in hills and nature, and also in history – you can travel across centuries in 20 minutes in Jerusalem. My dad is from Morocco, my mum is from Poland. I studied in Holland and live in Paris. The view I have of the world is from afar – from different perspectives.

Emma Crichton-Miller: Can you offer two examples of pieces in that show that represent an exciting, creative breakthrough or a particularly interesting process of decision-making?

Raphael Navot: It is almost true for all the pieces! It was certainly more challenging than anything that I’ve done so far in terms of assembly and craft. The ‘Admix’ desk for instance has so many languages of form in one piece and still I hope it retains a certain humility and emotional resonance. It was important for me, in terms of design, to achieve a form that is non-intimidating, not overwhelming, yet is very remarkable. That was a difficult balance to achieve – and also to find a carpenter who can make a desk that has nothing about it that is stable in form. I was lucky enough to find an amazing guy called Casimir Ateliers.

In terms of Friedman Benda specifically, they embraced comfort when I said that I didn’t want to create a piece that was visually stunning, but uncomfortable. I want it to be used. I want it to be misused. I want it to be worn out, to age gracefully. It’s very important for me.

Emma Crichton-Miller: Where do you think your interest in comfort comes from?

Raphael Navot: Just being in a body. But I’m interested in both mental and physical comfort, and the link between those. I worked flat out for one decade, taking on almost anything, and then I had a burnout. I just stopped and asked myself: What are the values that I care to stand for as a designer? What is my responsibility when it comes to having a talent? What is my skill? So, yes, I started to focus on what I missed most.