By Wendy Goodman

Great Rooms: A visual diary by Design Editor Wendy Goodman.

Misha Kahn’s Sunset Park studio is next to a big transformer grid in a squat, still thoroughly industrial part of the city where he moved his operation two years ago from Bushwick. A broker “showed me a bunch of cool spaces and then he said he’d show me a sort of curveball, but it was really cheap,” he says. There’s no AT&T mobile service inside, so I had to knock forcefully to get his attention to let me in.

Kahn spent much of the pandemic “at home in Minnesota on my parents’ deck losing my mind,” he says. So rehabbing the new space was something to throw himself into. He opened bricked-up windows, fixed broken doors, and hauled out 20,000 pounds of trash. “I think something nefarious happened here,” he says, laughing at the disastrous state it was in. But he also took the time to experiment with new technologies useful in both the conception of and execution of his ideas.

Kahn graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2011 and was featured in the Museum of Arts and Design’s biennial in 2014. The next year, he collaborated with Gone Rural, a group of women who are weavers and based in Eswatini, for a show, “Scrappy.” His 2017 exhibition at Friedman Benda, “Midden Heap,” was a phantasmagorical journey of design objects, incorporating detritus washed up on the shores of Rockaway beaches — including, in one memorable case, a toilet seat scrubbed clean by the sea.

Right now, his works include glass tondi: circular sculptures he refers to as “portals.” He is also working a lot in clay and has some very out-of-this-world, comfy-looking upholstered pieces.

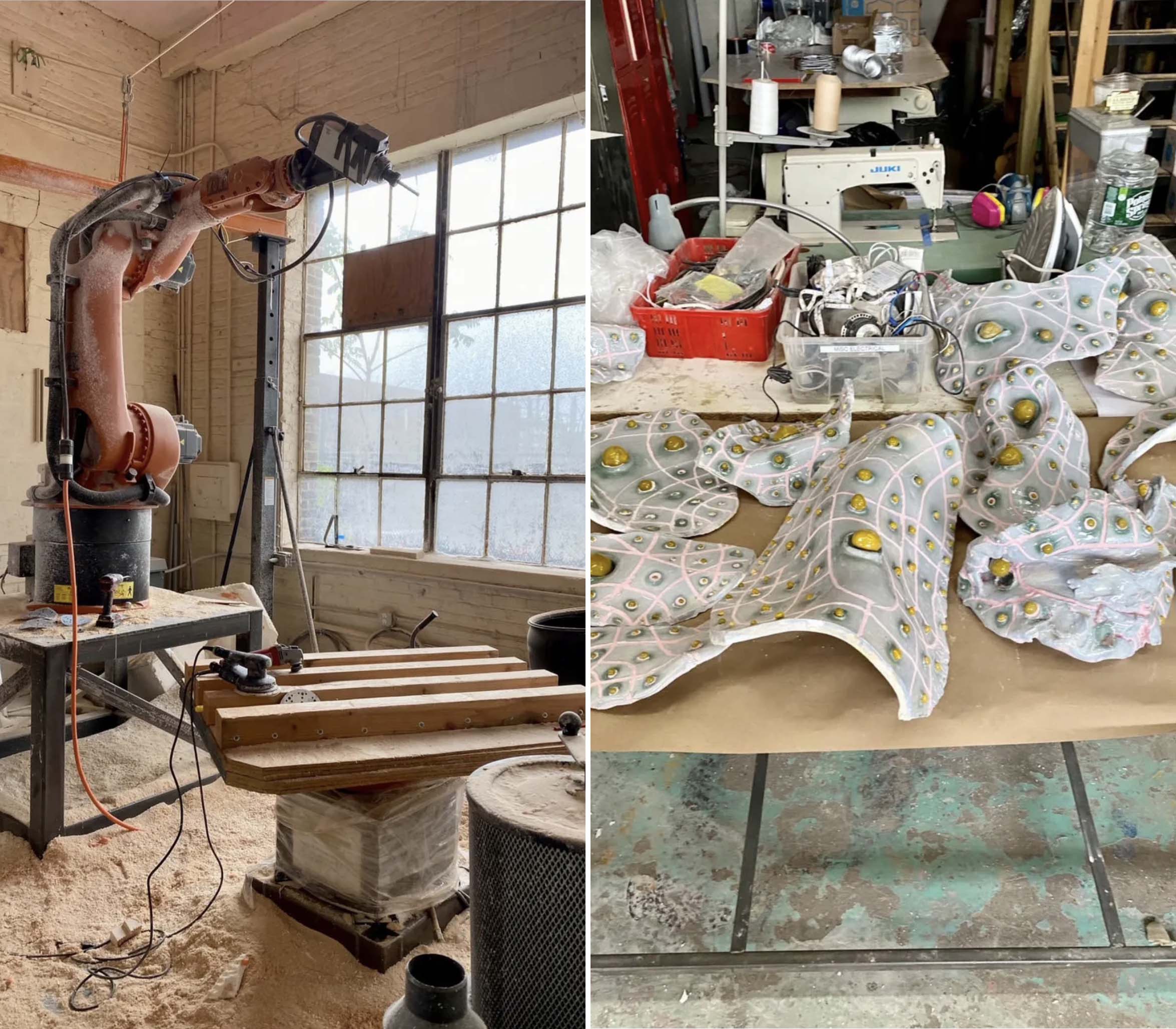

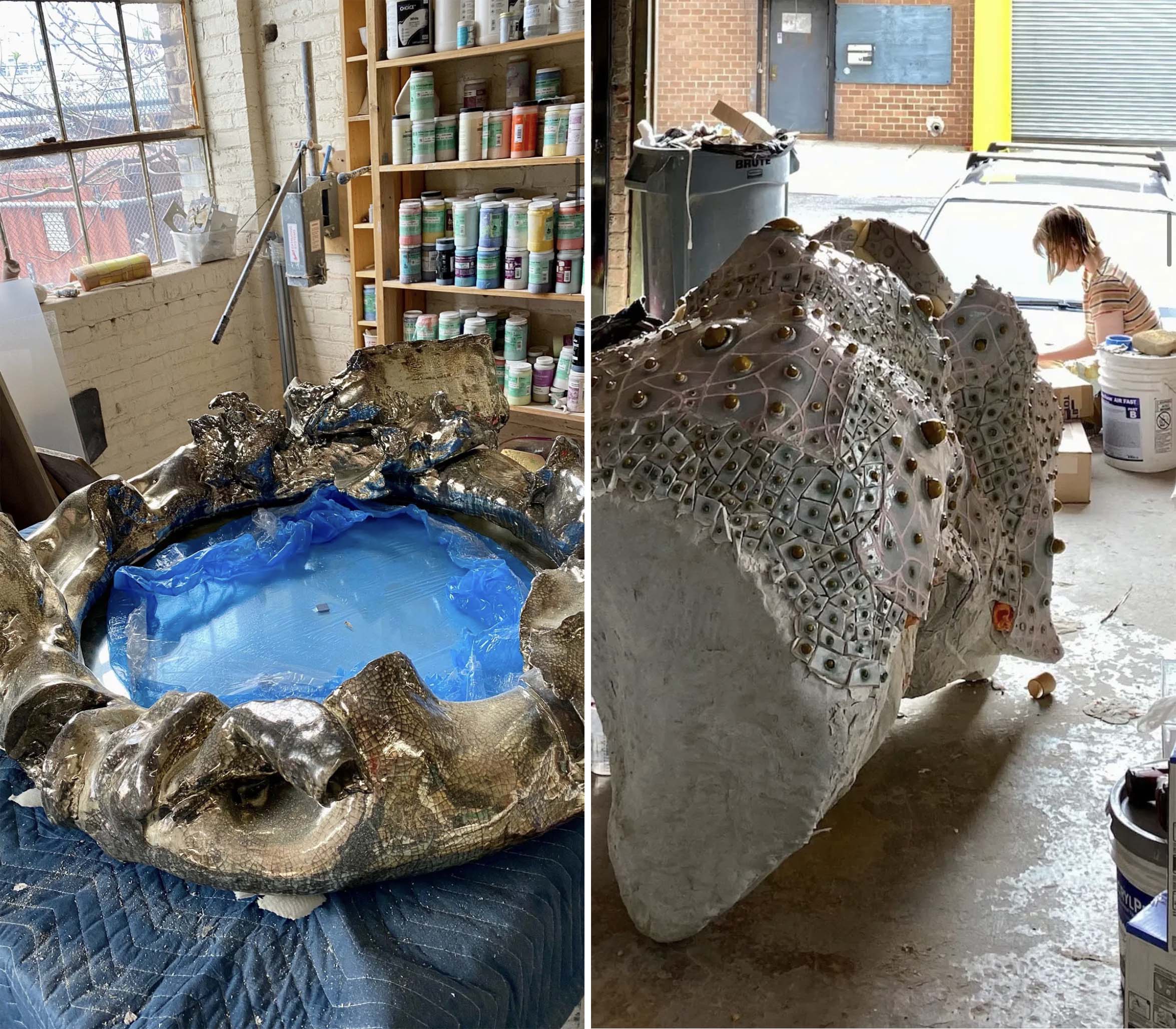

Kahn introduced me to his “clay-tile insanity,” starting with a table covered in fired clay tiles that will be the skin of one of the ceramic pieces in the show. The grout connecting the pieces is a key feature: “It lets us put the tiles together in segments, then conjoin them, and it’s very forgiving; if a tile doesn’t work, you can cut out the grout line and figure out something else.”

Over in one corner, there is a mirror frame that Kahn explains is ceramic and chrome, “another forgiving ceramic process; the chrome is like a silver-nitrate finish that we do afterward, so you can put stuff together and you can’t tell. So it doesn’t have to be in one piece.”

“This thing over here is really psycho; it’s in progress,” Kahn says. It looks like a hulking sea monster that crawled out of the harbor and found refuge in the studio. He created the form in VR, then the robot carved it, then they draped it with clay. “So in the end, I think, it will read as all mosaic when we finish grouting all of it.” What’s it going to be for? “Although I am dabbling in dark arts of nonfunctional things, this one is going to be a dresser, so there are drawers in it. But I think when it’s done, you won’t be able to see where the drawers are.”

Kahn’s work is no longer totally handmade — at least by human hands. I met a giant dinosaurlike robot helper that had a room of its own, surrounded by mounds of fine, sand-colored sawdust shavings. “This is robot No. 1,” he says of the machine poised for action. “I have a second one that is working around the clock in Germany painting. This is just kind of like the carving room.”

The machine has expedited the execution of Kahn’s designs. “It’s made the process very fluid,” he says. “I can draw something and then it carves it..”

This process lays the foundation for the larger pieces. “I made the form digitally,” he says, and the robot milled it, “but then there is obviously the ceramic process made with fingers.” The human touch is still essential.

The robot was acquired from a “used-robot conglomerate” and, Kahn guesses, might have been used in something like a car factory. “We are reprogramming it to do lots of things, which has been like a wild new adventure,” he says. “I feel like the studio now is half-and-half — some people are really computer-y, and some people are really tactile, and I think it’s a nice blend.”

We next step into a room with a sunken dining and work area below, with a large window overlooking the maze of the transformer.

“It’s wild when it rains because you hear all the transformers hissing and popping. But I got kind of lucky with the plants,” he says of the free-form wisteria entwined in the chain-link fence cordoning off the transformers. He then gets to work unwrapping two upholstered pieces that had just been delivered that day: a large sofa and a chair.

“The upholstery has definitely gotten more complex,” he says, unwrapping plastic cellophane from the pieces. He is working with two upholsterers, one of which he has partnered with for years. “It’s run by a guy from Oaxaca,” he says. “It’s all hand-stitching, and the draping and sewing is, I feel, an activity of patience and skill.”

Kahn is making another version of the sofa in Italy. “It’s a tour de force,” he says. “It’s kind of the opposite of this. This one is so hands-on, and the one in Italy is all done on the computer … The whole thing fits together without any hardware.”

He then re-covers the pieces as he tells me they discovered that a possum liked to come in at night for cozy spot to bed down. “We had a studio couch in here,” he tells me, “and [the possum] would always come in and sleep in the same spot; you could see the dent that he made.” How did he know it was a possum? “We saw him on the security camera!” he says, laughing.

As we head toward the stairs to the second floor, you can hear the mechanical humming and clicking of machines talking to one another — and, sure enough, once at the top, there are 15 3-D printers whirring away in a language of their own. “They are busy making chair-leg parts,” Kahn says. “You need talented people and talented machines.”

Beyond this room is Kahn’s office with his bulletin board and trove of objects plus drawings and samples of the 24 new pieces he is making for Art Basel, which opens on June 14. The show at Friedman Benda opens on June 2. “This is harvest time,” he says with a big grin. “And then I’m going back to planting seeds.”

Kahn’s office.

All photographs: Wendy Goodman.

“Style Without Substance” is on view at Friedman Benda from June 2 through July 1.