By Eliza Jordan

Last summer at Nomad St. Moritz, the French multidisciplinary designer Raphael Navot presented an armchair created in collaboration with Loro Piana Interiors named The Palm Duet. Created amid the global pandemic from afar, the soft chair was regarded for its sinuous shape — a take on the shape of the palm of a hand—and its use of a luxurious material named Cashfur from the Italian maison.

“What we have immediately loved from Raphael’s work is his incredible taste, his love for neatness, elegance, for what is essential and perfectly crafted,” said Francesco Pergamo, Director of Loro Piana Interiors. “We knew he had a passion for natural materials, for excellence, for creating timeless objects, not caring too much for trends. Well, it is exactly what has always inspired Loro Piana and what we inject into our solutions for interior decoration. Raphael’s creativity and our materials just came naturally together.”

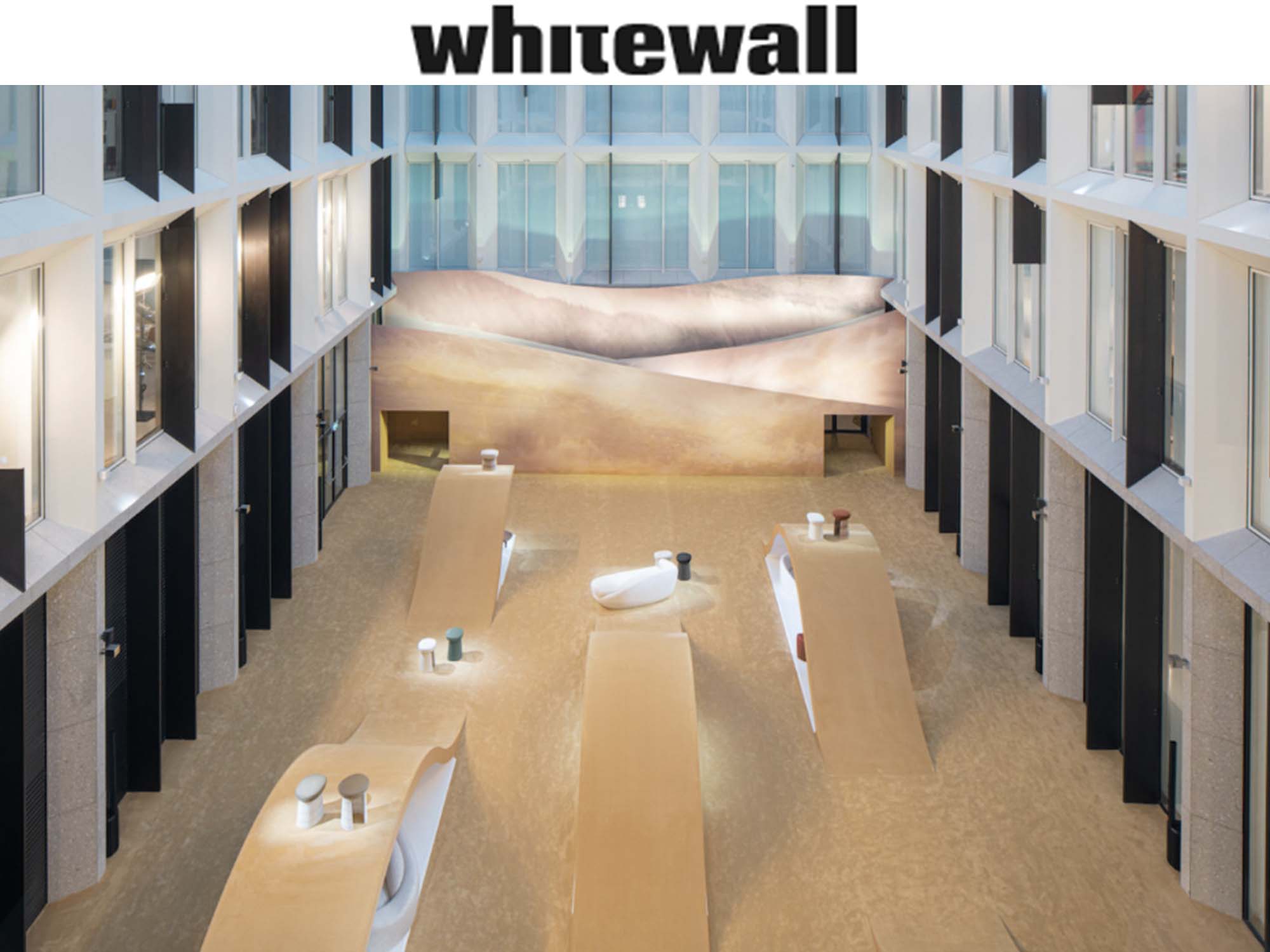

Today, in celebration of Milan Design Week 2022, the designer returns with Loro Piana Interiors for an elaboration of The Palm Duet with several new styles. In “A Portrait of Comfort” at the brand’s headquarters at Via della Moscova 33 in the Brera district, a soothing installation of dunes made of atmospheric images and materials hosted sofas, méridiennes, armchairs, stools, side and coffee tables, and the reimagined Palm Duet chaise lounge with an ottoman. This time, too, new pieces were created with an array of fabrics aside from Cashfur, including linen and cashmere, and special details—like removable tops of stools acting as trays, and elongated attached armrests used as a shared seat—were incorporated.

“There’s something about the whole collection that is about the fabric, about the sensorial effect. When you pass by, you’ll see so many people touching the edges, the fabric. They’re really drawn to the touch,” he shared with Whitewall at the presentation. “So, the forms are really about that and about these dynamics. More than anything, it’s about changing the typology of furniture—and the idea of how it carries you. That’s the hand that holds you. That’s why it’s called the Palm, because it’s about how it can hold you and engage you.”

To hear more about his second collaboration with Loro Piana Interiors and what he’s presenting at Friedman Benda later this year, Navot spoke with Whitewall.

WHITEWALL: When you created your first pieces for Loro Piana Interiors, what was your starting point with The Palm Duet? Were you seeking comfort?

RAPHAEL NAVOT: It was really Covid. We wanted to do a chaise that is not a chaise longue or an armchair but about this idea of travel. It was really an association with first class. When we say that, we talk about ergonomy with furniture but not really with sofas; we don’t really associate them the same way. But that’s what the chaise longue was about in the French culture—the archetypology of furniture. For me, this is an armchair that’s meant to be shared. The armrest is treated as a seat, which is why it’s called a “Duet.” It’s about how you can use it at home, and it was an idea of making forms that talk about time and intimacy. It happened during Covid, so it evoked that, and the forms really became about that.

WW: What was the collaborative process like to make these pieces, if you were designing during Covid? Were you talking with Francesco Pergamo on Zoom or WhatsApp, and sharing ideas and pictures virtually?

RN: Yes, both. I was traveling through empty airports, too. It was a design I was working on, and I showed Loro Piana what I was working on, but it was a rendition of The Palm Duet, so it was born from that. You can see the same features, so it’s all a language that was born from the first piece.

WW: You were drawn to Loro Piana’s Cashfur material, and have since worked with it many times. Why?

RN: It’s a great alternative to fur. Morally, it’s amazing. You’re not killing an animal to use the fur. There’s a moment where you push craft to its end and you end with moral questions: Is there a way to do it? At what cost? Not only is Cashfur an amazing solution because you have pure cashmere and amazing quality, but it’s monitored and fabricated by Loro Piana with a touch of silk on a flexible mesh. It’s like a dream. You can do anything with it and still with integrity. We’re not talking about crocodile skin. That’s not so interesting. The idea that you can work in a circular system and not a linear one, it’s amazing. And you can feel more comfortable with the craft.

I did a Moon sofa for Loro Piana for an event and they thought I was crazy to do it, but it’s such a strong fabric. And I do a bunch of furniture for Friedman Benda like that, too. With it, I can push the craft. It’s much stronger than what you think—in terms of fiber, aging of the color, friction. It was a big surprise. And the temperature, when you’re wearing cashmere, is regulated. There’s something about Loro Piana fabrics, as a fashion brand, and using them to translate as overlap stories—whether about the stitch or type of technicality.

WW: Franceso mentioned you shared many values—and one of those is creating things by hand. How do you embed that into your practice, especially with the rise in technology?

RN: I build a lot of the shapes, or sculpt them for the galleries. A lot of the time, I work with high technology and model things in 3-D. I like the mix between high technology and handmade. We can’t take tradition into the future without knowing what we can do now that we couldn’t do before. So, some of the ways that I calculate shapes, and calculate comfort, I am using technological tools to get the best form in order to protect the design. A lot of times, they’ll print the form that I made and work around it, instead of interpreting it. We use similar traditions the way upholstery is being made, but we use technology when we need it—and not just to have it. A lot of things are stitched by hand, and a lot of details can’t be done otherwise, like these fabrics. I’m generally obsessed with anything that has some integrity around craft and history—almost any material. This time, it was fabric.

I’m very much into craft, but not so much in a traditional way. For conception, I absolutely endorse the idea of what we can do today with technology that we couldn’t. But the actual making of the pieces, you feel it in the material. When you feel a material that hasn’t been touched by someone, it doesn’t feel the same.

WW: In October, you’re presenting a show with Friedman Benda. What can we expect to see?

RN: It’s going to be my first solo show. It will be important in terms of the craft we emplore, so it’s going to be very diverse. A lot of woodwork and bronze, new materials, oceanic plastic. Taling about craft in an actual way, instead of going back in time and trying to keep it there. Being in France, and Italy, there’s so much craft and knowledge and people who understand that. You can find artisans everywhere. But a lot of the times, there is a decorative element. In order ot brign that craft into the future, we don’t want so much of the decortive conotation of architecture and furniture. We like it to be detatched somehow, but we like it to be festive and dynamic. So the show will very much be about that. And of course, about comfort. In the Loro Piana content, it has to be within this understated, beautiful frequenece of the brand. At Friedman Benda, we’ll push that to the edge of where it can go.