By William Yardley

Lebbeus Woods, an architect whose works were rarely built but who influenced colleagues and students with defiantly imaginative drawings and installations that questioned convention and commercialism, died on Tuesday in Manhattan. He was 72.

His death was confirmed by a longtime colleague, the architect Steven Holl. Details were not immediately available.

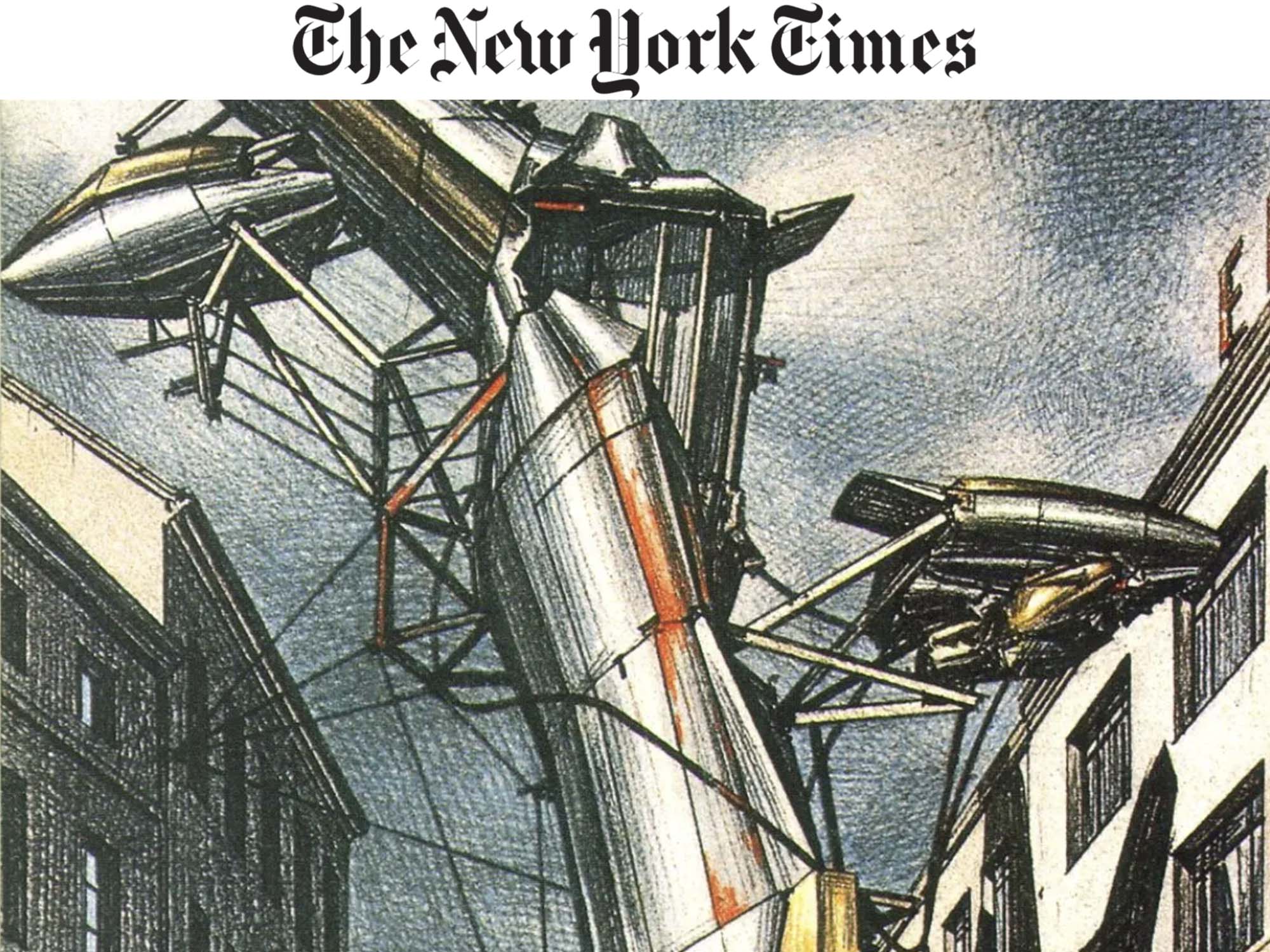

In an era when many architecture stars earned healthy commissions designing high-rise condominiums or corporate headquarters, Mr. Woods conceived of a radically different environment, one intended for a world in conflict.

He conceived a post-earthquake San Francisco that emphasized its seismic vulnerability. He flew to Sarajevo in the 1990s and proposed a postwar city in which destruction and resurgence coexisted. He imagined a future for Lower Manhattan in which dams would hold back the Hudson and East Rivers to create a vast gorge around the island, exposing its rock foundation.

“It’s about the relationship of the relatively small human scratchings on the surface of the earth compared to the earth itself,” Mr. Woods said of his Manhattan drawing in an interview several years ago with the architectural Web site Building Blog. “I think that comes across in the drawing. It’s not geologically correct, I’m sure, but the idea is there.”

Mr. Woods’s work was often described as fantasy and compared to science-fiction imagery. But he made clear that while he may not have expected his designs to be built, he wished they would be — and believed they could be.

“I’m not interested in living in a fantasy world,” Mr. Woods told The New York Times in 2008. “All my work is still meant to evoke real architectural spaces. But what interests me is what the world would be like if we were free of conventional limits. Maybe I can show what could happen if we lived by a different set of rules.”

He spread his message from many platforms. He was a professor at Cooper Union, spoke at symposiums around the world and built sprawling temporary installations in Austria, Italy, Southern California and elsewhere. He also wrote a well-read blog.

Earlier this year, in a post explaining why he chose to become an architect, he said winning commissions was not a major motivation.

“The arts have not been merely ornamental, but central to people’s struggle to ‘find themselves’ in a world without clarity, or certainty, or meaning,” he wrote.

Mr. Woods often criticized what he saw as a complacent and distracted status quo in his field. But his colleagues said his commitment to creating an alternative showed that he had hope.

“If he really felt as cynical and skeptical as he sometimes would say, then why the hell draw this stuff?” Eric Owen Moss, an architect and longtime friend, said in an interview on Wednesday. “There’s an incredible amount of power just in the draftsmanship. He’s like Durer — you know, woodcuts, 15th-century stuff. There’s content — intellectual content, social content, artistic content, political content — but the very act of making these sort of remarkable things and his drawing capacity made a kind of new language.”

Christoph A. Kumpusch, a longtime friend and colleague who, like Mr. Woods, taught at the Cooper Union in New York, said Mr. Woods “wanted life and architecture to be a challenge” and “always wanted us to feel a little uncomfortable in order to make things change.”

Mr. Kumpusch collaborated with Mr. Woods on the only permanent structure he built, a pavilion for a housing complex in Chengdu, China, designed by Mr. Holl. Called the Light Pavilion, and completed in October, the pavilion is reached by several glass and steel bridges and ramps.

Lebbeus Woods was born on May 31, 1940, in Lansing, Mich. His father, an engineer in the military, died when he was a teenager. His survivors include his wife, Aleksandra Wagner; their daughter, Victoria; and a son, Lebbeus, and daughter, Angela Bechtel Woods, both from a previous marriage, and seven grandchildren.

An exhibition of work by Mr. Woods will be on display at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art beginning in February.

“Outside-the-box” thinking has become a cliché used in advertising, corporate strategy and politics, Mr. Moss said, but Mr. Woods took it to another level.

“There’s another box, and he’s outside it,” he said, “He’s outside all the boxes.”