By Jonathan Goodman

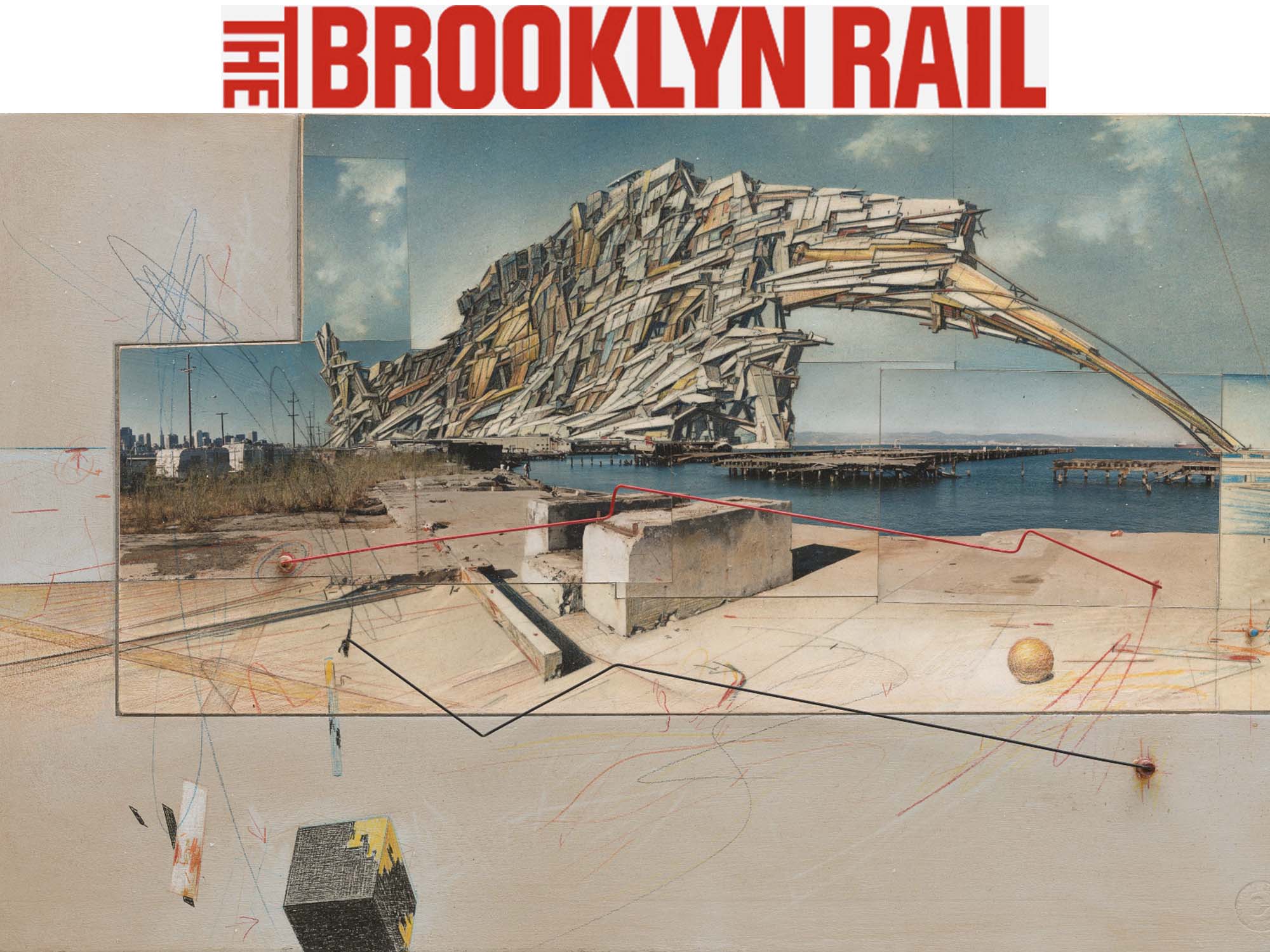

Lebbeus Woods’s death in 2012 was a considerable loss to the architectural world, as the fine new show of his drawings and maquettes at The Drawing Center demonstrates. Woods’s capacity as a gifted technician and radical theorist of contemporary architecture resulted in a singular body of work that undermined current notions of how to successfully create places in which to live and work. He never formally practiced architecture and thus had scant experience in building actual structures. He was interested in the rewards of making buildings, but his real contribution to the field lies more in his attention to expanding the field’s horizons by imagining structures in contrast with the world of conventional architecture.

As a draftsman of real power, Woods created drawings and models that indicate a sharply critical mind; his designs refuse to play along with tradition, enabling his images to call attention to themselves or to float free of the structures with which they interact. A key facet of his achievement is his amazing facility with the genre of pen-and-ink drawings. The drawings themselves, some of them single works and others done in small sequences, are remarkably complex and beautiful, particularly because of the astonishingly intricate cross-hatching. The artist’s sense of detail is so fine it often tricks the eye into thinking it is looking at an engraving, as occurs in “Photon Kite” (1988), a highly meticulous drawing of a futuristic construction suspended in space.

There is a powerful sense of monumentality in the works. The drawings feel like visionary studies of architecture’s conceptual dimensions, which include the recognition of loss and the treatment of buildings badly harmed by conflict. The structures that Woods imagined attach themselves to other damaged buildings in historically traumatized cities such as Berlin and Zagreb. His bodies of work also include general improvisations on a theme, such as the War and Architecturebook, in which his imagination looks to keep memory alive rather than destroying all traces of conflict. Additionally, there is an especially strong series of drawings named Einstein Tomb (1980) that pays tribute to the great physicistand explores how architecture might fulfill the demand for memorial. Consisting of graphite and ink on board, the four pictures seem to depict dark matter, a space that holds immensities. One image consists of tower-like structures: cones and rectangular constructions that suggest the landscape of a major metropolis. Another offers a cross-shaped structure, with organic forms on the left side pushing out of the edifice and cutting into space. The background is completely dark, except for a single white line set behind the central axis. A maquette of this simple frame stands nearby, realizing an image that is otherwise terrifyingly intangible, left out in the endless emptiness of space.

“Berlin Free-Zone 3-2” (1990) addresses the problem facing the post-war architect—namely, how does new architecture advance a sense of history when conventionally its goal has been to remove any trace of conflict by building anew? In one drawing, we see an insect-like construction jammed into an open space between buildings. It appears to be climbing the wall of the nearest structure, one of its limbs grasping onto a second building’s façade. Both compelling and strange, the hybrid building/contraption/monster presents structural complexities that could hardly find footing in the real world. Over the course of his lifetime, Woods became known for such idiosyncratic building forms, embodying a creative ethos not dissimilar to Frank Gehry. Yet Woods belonged to no real movement except the one generated by his own creativity, in part because his art was too extreme to be actualized.

The Sarajevo series (1993 – 96), part of a larger grouping called War and Architecture, continues Woods’s attention to buildings and neighborhoods damaged by strife. Through these works, one begins to understand how Woods sought for an architectural order that aligns both with memory and social morality. One of the drawings from High Houses (1997), another subset of War and Architecture, shows two dwellings lifted up several stories by long poles. Wires connect the two homes to lower buildings, while a massive structural façade presents more than a few odd formations embellishing its exterior. The high houses look less like buildings than mechanical monsters—creatures from the Jurassic age. Woods’s obsession with a pure architecture, one constrained neither by convention nor by the accommodation of historical legacy, reminds us that visionary drawings hold a place in the future creation of structures which may not be capable of being built (yet). His ideas have and will continue to function as brilliant constructions for our time.