By Deyan Sudjic

What makes the work of the Chilean collective GT2P stand out is its deft ability to play at opposite ends of the design spectrum at the same time. They are rooted in the specifics of a very particular place, but equally part of the global conversation. They are fascinated by digital techniques, but also by craft skills. They share a communal identity, but they each make a different contribution to it.

GT2P are based in Santiago, which is about as far from the conventional centres of the design world as you can get, but they have shown in New York, with Friedman Benda gallery, in Melbourne at the National Gallery of Victoria, at Milan Design Week, and in London, where the Design Museum has their ‘Suple’ bench in its garden. ‘Suple’ is Chilean slang for ‘workaround’, or makeshift and patched up. The core of the bench is a cast bronze five-way joint that connects three vertical and two horizontal timber beams, one of them supported by a piece of rock, to create a stable seat with a mix of rough and smooth, formal and informal.

Their studio is in a residential building in a low-rise modernist suburb, built in the 1950s. It’s a long way from Santiago’s city centre, where art deco towers and the Museum of Fine Arts, with its glass roof prefabricated in Belgium, sum up the sense of an early 20th century European city exiled at the edge of the world. The studio is equipped with computers and 3D printers as well as kilns.

In all its messy splendour, GT2P’s Catenary Pottery Printer stands dripping liquid clay onto the floor. It’s a contraption that Antoni Gaudí would have recognised from his plans for creating complex curves for the vaults of La Sagrada Familia. It has a homemade timber frame construction that somehow suggests a puppet theatre, which supports an adjustable muslin sheet to give the studio an analogue, hands-on version of parametric geometry software. The complex curves of the muslin surface can be adjusted by moving weights back and forth along the x or y axis, just as a computer programme would. But here the form is created by pouring layers of liquid clay, known as ‘slip’, over the muslin, and allowing the clay to set. It has been used to design a range of small domestic objects.

GT2P’s tongue-twister of a name stands for Good Things To People. But it also contains the names of two of the group’s founders, Guillermo Parada and Tamara Pérez who met while they were architecture students. The group also includes Victor Imperiale, Eduardo Arancibia and Sebastián Rozas. Parada does the talking, Pérez is chief maker, Rozas leads on their architectural projects, Imperiale ensures that they are all digitally literate. Arancibia studied civil engineering and has an MBA. They have designed restaurants, installations, playgrounds, and furniture.

Working with Marc Benda of Friedman Benda, they have invested a lot of time working out how to use one of Chile’s most abundant raw materials: lava. With scores of active volcanoes to choose from, they have collected material from four in particular: Osorno, a 2562-metre-high volcano with its pure conical form and snow-topped peak rising high over the shores of Lake Llanquihue, is particularly beautiful. It has a difficult nature that must be treated with respect. Osorno is a stratovolcano, a species made up of alternate layers of lava, pumice and ash that is liable to violent eruptions on a massive scale without warning. Calbuco, another of the volcanoes that they worked with, last erupted five years ago throwing up an ash cloud 15 km high and threatening settlements as far away as Argentina. They have also worked with material from the Chaitén caldera and from Villarrica, one of the few volcanoes in the world with a permanent lava lake.

After months of experiments they came up with a laborious technique that involves grinding up blocks of lava into a powder, then cold moulding it in stamped powder moulds made from materials such as aluminium or graphite, which will not melt at temperatures that turn lava molten. These in turn are placed in stoneware boxes and fired in a kiln where the lava powder melts, replicating a lava flow in a controlled eruption.

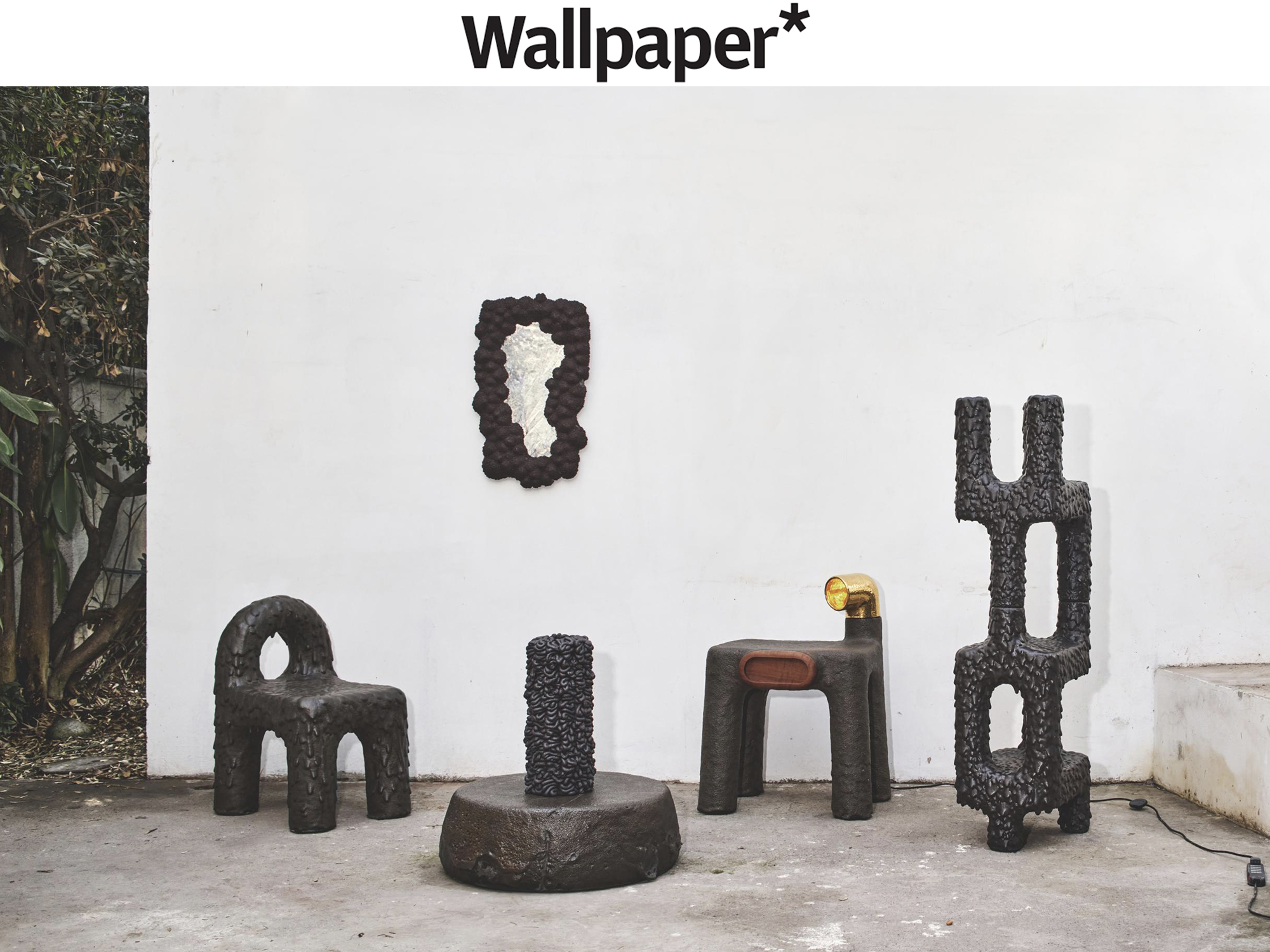

The heat of the kiln determines the strength and colour of the final piece. Lava starts to melt at 1,180 degrees Centigrade, resulting in a red colour. Go up to 1,200 degrees and the material turns grey-black. At 1,300 degrees, which you need to get the viscosity inside the kiln to make more complicated shapes, the colour is brown. Some of their pieces are 3D-printed before they are fired in the kiln. GT2P call this technique ‘paracrafting’. It’s their way of combining physical craft with the discipline of the contemporary technologies of parametric manufacturing.

As GT2P put it, it’s a way to ‘manufacture a landscape’, an expression that reflects the tension between the rigour of mathematically derived formulae that shape a pure form, and the acceptance of the accidents of production processes.

The most recent result is a complete chair, the ‘Monolita’ chair, an extraordinary object made to celebrate the studio’s 10 years in practice. It is the first time they have pushed the material this far. The fundamental form, created in the mould, is a chair reduced to its graphic essentials. But the surface bubbles and drips, a version of the molten lava that the chair once was, seemingly made into a frozen solid. GT2P have used the same techniques to create a range of other objects, a side table, with built-in light as well as screens and room dividers. The functional alibis are straightforward, but the way that these simple utilitarian objects are made, and the material that they are made from, asks wider questions about the meaning of creativity in the midst of a tidal wave of disruptive technologies that is transforming both design and art.