By Anna Sansom

LATIN AMERICAN DESIGN may have long been overshadowed by that of Europe and North America, but in recent years it has claimed centre stage at art fairs and auctions. The important role of twentieth, mid-century Brazilian Modernists is increasingly recognised by collectors, while contemporary Brazilian designers are enjoying the limelight in international galleries.

Piasa’s Brazilian Design sale on December 10th 2020 underscored the growing demand for works that leading modernists José Zanine Caldas, Joaquim Tenreiro, Oscar Niemeyer, Jorge Zalszupin and Sergio Rodrigues created in Brazil from the 1950s to the 1970s. It illustrated the designers’ predilection for rounded lines, organic forms and wood as a material.

Standouts included pieces that Caldas made from pequi wood in 1977: a large dining-room table fetched €123,500, and a sculptural sofa carved from a tree trunk reached €97,500. Other highlights were Zalszupin’s octagonal low table, ‘Mésa Petala’ (1959-1965), which reached €18,200, as well as Niemeyer’s ‘Chaise Rio’ (1977), a rocking chair that exemplifies the elegant curves and sinuous forms of Niemeyer’s renowned architecture, and J. D. Decoracoes’s delightful dessert trolley on wheels (circa 1950s) – both of which sold for €16,900.

Brazilian Modernism emerged as a synthesis of ideas brought over from Europe and their assimilation by Brazil’s own designers. A pivotal event was the Modern Art Week in São Paulo in 1922; six years later, the first Modernist house, Casa Modernista, by Ukrainian-born architect Gregori Warchavchik was constructed. Portuguese-born Tenreiro, Polish-born Zalszupin, Italian-born Lina Bo Bardi, and Carlo Hauner and Martin Eisler, who were Italian and Austrian respectively, all immigrated to Brazil, encountered local designers and embraced the use of natural materials, such as wood and caning. The furniture pieces that Tenreiro made for Hotel Cataguases, designed by Niemeyer, exemplify his contribution to Brazilian interior design. Moreover, Niemeyer’s architectural design of Brasília, Brazil’s federal capital – for which Lúcio Costa was the urban planner – helped shape the modernist vision.

It would not be until 2005 that some of the pieces first appeared at auction in New York, when Tenreiro’s lacquered rosewood ‘Chaise Longue’ flew past its $15,000-$20,000 estimate to $48,000. According to Florent Jeanniard, Sotheby’s co-worldwide head of design, within the space of 15 years Brazilian Modernism has attracted collectors worldwide – particularly from Hong Kong, Los Angeles and Paris. “It’s a recent market, with furniture and objects from the 1950s and 60s to contemporary design, with much more yet waiting to be discovered,” Jeanniard says. He cites a three-legged table by Tenreiro that fetched €112,000 at Sotheby’s in June, as a record.

An early proponent of Brazilian Modernism is Mercado Moderno, co-founded by Alberto Vicente and Marcelo Vasconcellos in Rio de Janeiro in 2001. Back then, Vicente and Vasconcello owned an antique shop and became interested in the furniture collection of a Brazilian publishing company that had gone bankrupt. “We realised that the level of the pieces was excellent; they were sold in large lots at very low prices as there was little appreciation and understanding of their real value, historical or otherwise,” they say. Intuitively, they seized the opportunity to snap up the lots. “We were faced with real treasures – the woodworking craftsmanship especially fascinated us,” they add.

Mercado Moderno was founded 16 years after Brazil emerged from the military dictatorship that had ruled the country from 1964-1985. Of the gallery’s early days, Vicente and Vasconcello recall, “Initially, Brazilian modernist furniture didn’t arouse the interest of collectors – in fact it was despised, donated and considered something of low value.” They recount how the economic boom of the years that followed attracted more foreigners to Brazil, which helped to nurture a market.

R & Company in New York has championed Brazilian Modernism since its co-founder Zesty Meyers first became passionate about Niemeyer’s architecture, staging Vintage Brazilian Design, the first of several exhibitions, in Geneva, Switzerland, in 2013. In Europe, Nilufar in Milan staged a large solo show dedicated to Bo Bardi during Milan design week in 2018, focussing on the works of Estúdio d’Arte Palma, which Bo Bardi co-founded with Italian architect Giancarlo Palanti. Galerie Chastel-Maréchal in Paris put on a group show on Brazilian Modernists in 2018. And Side Gallery in Barcelona has long been selling works by Brazilian Modernists, as well as by several upcoming Latin American designers.

THE PIONEERING CAMPANA brothers have put Brazilian contemporary design firmly on the global design map over the last few decades. Against the backdrop of the military dictatorship’s twilight years, the São Paulo-based duo established their studio in 1984 and founded an institute in 2009 to preserve their legacy and launch social and educational programmes.

Often collaborating with local communities and craftsmen, Estudio Campana’s prolific production incorporates assemblage and the imaginative use of everyday, inexpensive materials whilst evoking Brazil’s bright colours, street culture and the vernacular of favelas. The exhibition ‘Projects 66: Campana/Ingo Maurer’ at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1999 brought them international recognition. This placed the innovative lamps of the renowned German lighting designer in juxtaposition with the the Campanas’ low-tech pieces, including the ‘Vermela Chair’ (1993), edited by Edra, which is created from 500 metres of red rope looped abundantly over an aluminium frame.

Vibrant, tactile and humorous, the Campanas are also driven by an ethic of sustainability and the desire to rescue and preserve artisanal technologies. This is seen with the ‘Favela’ chair (circa 2003) haphazardly made from small, narrow pieces of Brazilian Pinus wood, one of which sold at Sotheby’s New York in 2013 for $10,000. Think, too, of the chairs and sofas made from soft stuffed animals, such as the ‘Dolphins and Sharks’ (2002) chair, and the ‘Sushi’ and ‘Harumaki’ (2002-2014) furniture collections made from carpet-and-rubber rings.

More recently, their ‘Hybridism’ exhibition at Friedman Benda in New York in 2017 reflected “on the Amazon devastation, the political situation in Brazil and the rest of the world [and] was a sort of catharsis,” Humberto Campana has said. Found sticks and tree bark are cast in bronze into the bases of ‘Branches Sofa’ (2017) in a meditation on the ecological situation.

The work of the Campanas can be found in the collections of the Centre Pompidou and Musée Des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Germany, and the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo. The brothers are represented by Firma Casa in São Paulo, Giustini/Stagetti in Rome, Carpenters Workshop Gallery and Friedman Benda, after being initially supported by Moss Gallery, and pieces also appear at auction. Last February at Phillips auction house in London, a KAWS Chair Black, from a collaboration in 2018 with the artist KAWS, sold for £118,750 against an estimate of £70,000 – £90,000.

“The Campana brothers are pioneers of Brazilian contemporary design and their wide breadth of creative output is unparalleled,” Loïc Le Gaillard, co-founder of Carpenters Workshop Gallery, says. “Moving between the boundaries of art and design, their evocative and humorous work achieves some notably Brazilian characteristics – bright colours, creative chaos and the triumph of simple solutions.”

Equally, Marc Benda from Friedman Benda, remarks: “I would credit the Campanas’ studio for having almost single-handedly rekindled interest in South American design while forcing the world to reconsider the region for its ability to innovate and substantially expand the dialogue.”

NATURAL MATERIALS AND sustainability are common interests shared by several other Brazilian designers today. Hugo França has been sculpting furniture since the 1980s from pequi, oiticica, barauna and ipê fallen woods left behind from the rampant deforestation of the Atlantic Forest in southern Bahia. Seeking a singular harmony between proportions, volume and cuts, França allows himself to be guided by the grains and shapes of the wood itself. “All of the sculptural furniture and sculptures that I create preserve the existing design found in the natural shape or texture of the wood,” França says. “I simply unveil what has already been determined by nature.”

His first “action” was to produce furniture pieces from old canoes made by Pataxos Indians, which were no longer used for fishing. He considers a chaise longue made from the stern and bow of a canoe to be his first significant piece. The removal of trunks followed, França enlisting a team to transport them to a large forestry-waste storage area in his studio. His current challenge is removing a monumental Pequi Vinagreiro tree from the forest – an operation which, despite a special reinforcement being made on the truck, is still incomplete three months later. In the meantime, França is making his largest-ever monumental sculpture from the remains of chainsaw cuts that will be placed at the front of his atelier in Trancoso, Bahia.

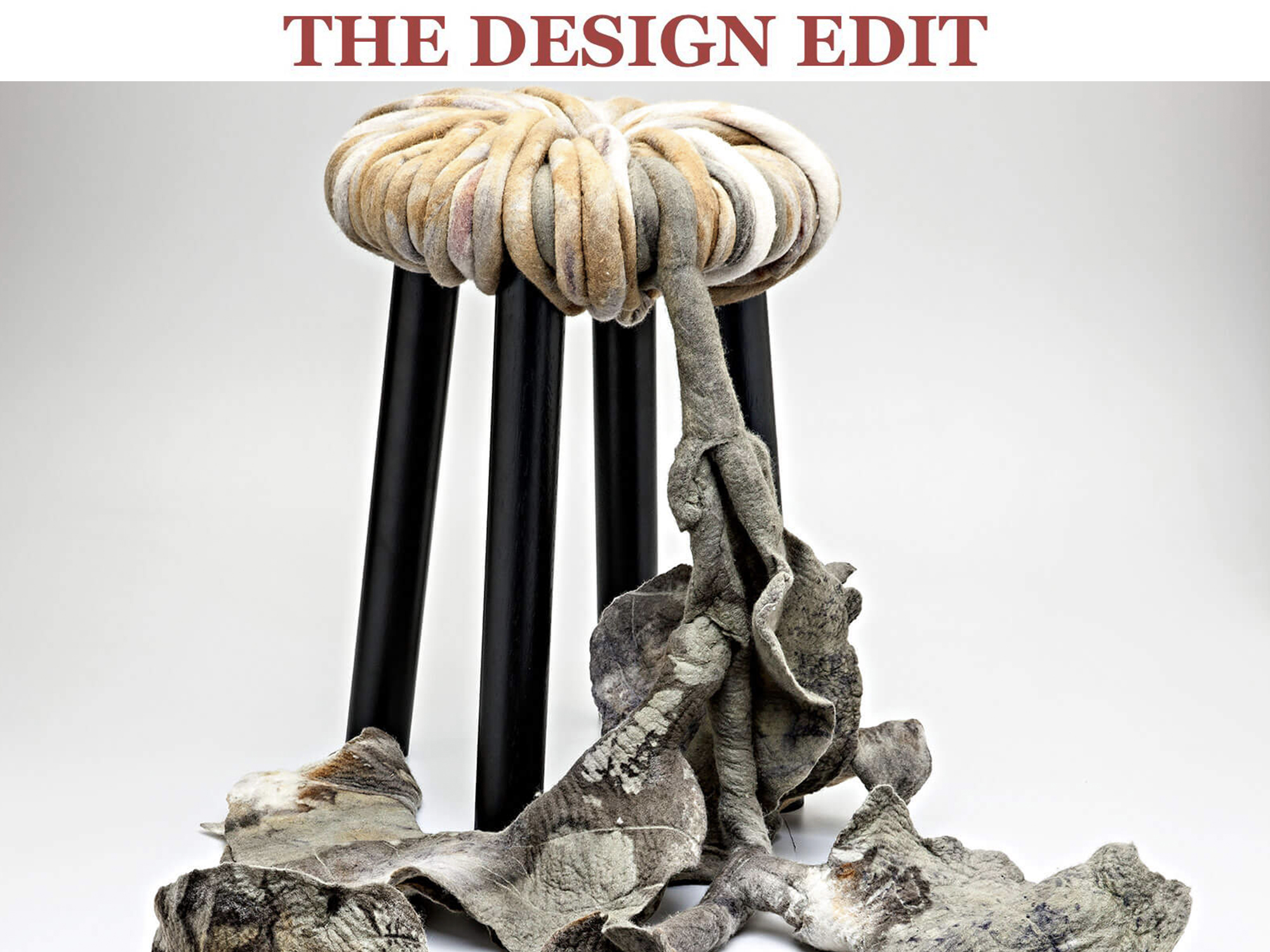

Meanwhile, in the south of Brazil, Inês Schertel makes elegant furniture and vases from the wool sheared off the sheep on her husband’s farm, her production partly determined by the cycles of nature. With her hands, she felts the raw material of wool and also uses wood, leaves, tree bark and botanical dyes. “I call my process ‘slow design’, not so much because of how long it takes for the pieces to be finished but because of the way I relate to the time that is necessary for each step to be completed,” Schertel explains. Her latest creations, including vases, acoustic panels and stools, are made from Australian merino wool, to which she is drawn for its aesthetic and functional qualities.

The younger generation of designers is adopting a different, more conceptual approach in their work. Vicente and Vasconcello from Mercado Moderno refer to how Mameluca Studio (founded in Rio de Janeiro in 2010) “manages to create pieces with a clear influence of the works by [the artist] Lygia Clark but at the same time absolutely innovative.” For instance, for the ‘Uiurar’ (2014) series of multi-functional furniture, the studio bound and tied pieces of wood using ratchets, drawing inspiration from the mooring method used by Brazilian indigenous tribes.

ELSEWHERE IN LATIN America, a rich diversity of studios is gaining international acclaim. Among these is the Chilean studio gt2p (Great Things To People). For Design Miami/ Podium earlier this month, gt2p was commissioned to make a temporary, outdoor installation, ‘Conscious Actions’: a turquoise structure with three swing seats and overhead red wings that rippled with each swing’s movement.

The installation was designed in response to the curatorial brief by Anava Projects to reflect on the energy consumption of human beings. “The project addresses a global issue and is not related to a Latin American identity, but to formal, material studies by our studio … in order to create an experience for transmitting a message,” Guillermo Parada, gt2p’s founder, explains.

Research being crucial to gt2p’s practice, an earlier project, ‘Remolten’ (2017), which was exhibited at London’s Design Museum in 2018, developed from research into volcanic lava. Lava from four of Chile’s 2,000 volcanoes underwent various processes of being granulated, remelted and cooled in order to create stoneware objects. “Although the project was born from research in a particular region of Chile, the knowledge produced there is universal in investigating a raw material found in many parts of the world,” Parada says.

While gt2p is contributing to Chile’s contemporary visual culture, the transdisciplinary Pedro Reyes is a major figure in Mexico. Having trained as an architect before becoming an artist, Reyes proposes playful solutions to societal problems. He has created musical instruments from dismantled weapons seized by the Mexican army from drug cartels and has been commissioned to make an interactive sculpture, ‘Leverage’, combining a see-saw and a roundabout, for the Fundación Malba in Buenos Aires. Design-wise, Reyes has made a series of furniture, ‘Tripod’ (2018), from volcanic stone, inspired by Mexican tribal objects and by the fact that most pottery and stone artefacts from Pre-Columbian times had three legs.

Numerous other talents are helping to define Latin America’s contemporary design scenes. Count in the Santiago-based Rodrigo Pinto, who makes startling concrete-and-ceramic furniture in unusual forms; Bogota-born, Brooklyn-based Ana Buitrago who sculpts ceramics, such as vases and lamps, that draw inspiration from pre-Columbian objects, and Mexico’s Platalea Studio (Lilia Corona and Rodrigo Lobato) who make richly coloured dinnerware and lighting in partnership with local craftsmen.

Regarding the plurality of visions, Benda comments: “The global design dialogue has expanded in scope and ambition over the past couple of decades and Latin American design has allowed for very diverse expressions that are hard to characterise with just a single point of view.”

The exciting breadth of discovery can only become amplified as Latin American designers gain greater international exposure.