By Gay Gassmann

Though it was disappointing at the time, perhaps not getting into the architecture school at the Cooper Union in New York City was a blessing in disguise for prolific multimedia artist Daniel Arsham. Instead, he enrolled in the college’s equally famous art school and so, rather than making buildings, he pivoted to making art. But, ever since, he has explored issues of architecture, engineering, and a fictional sort of archaeology in work that always evokes a poetic conversation between past and future.

Upon graduating in 2003, Arsham returned to his hometown, Miami, where he and a group of friends rented a 1930s bungalow-style house, gutted it, and opened a gallery space called, fittingly, The House. Here, the group exhibited every kind of art imaginable, from paintings to film and performance. Arsham also continued pursuing his own art practice. At around the same time, Art Basel launched its yearly Miami edition, and there was increasing interest in local artists among the international art-world grandees who descended on the city for the fair. French art dealer Emmanuel Perrotin paid a visit and “offered us a group show in Paris,” Arsham relates. “I had my first solo show with him in 2005, and from then he began representing me on a larger scale. We’ve grown together.” (In fact, his latest show at Perrotin’s Paris space opens next month.)

A few years later, Arsham cofounded Snarkitecture with Alex Mustonen, a friend from school. It was a way for Arsham to execute projects that were closer to architecture. “My work often manipulates architectural surfaces, and sometimes I need architects and engineers to help me work out the language. Snarkitecture has taken on a life of its own, and now people might not even know I’m associated with it.”

Arsham’s practice has grown to include editions he calls Future Relics (everyday objects treated as archaeological finds), large architectural installations, fashion collaborations with the likes of Kim Jones for Dior Men and streetwear brand Kith, and several years of collaborating with the late master choreographer Merce Cunningham, doing set, lighting, and costume design.

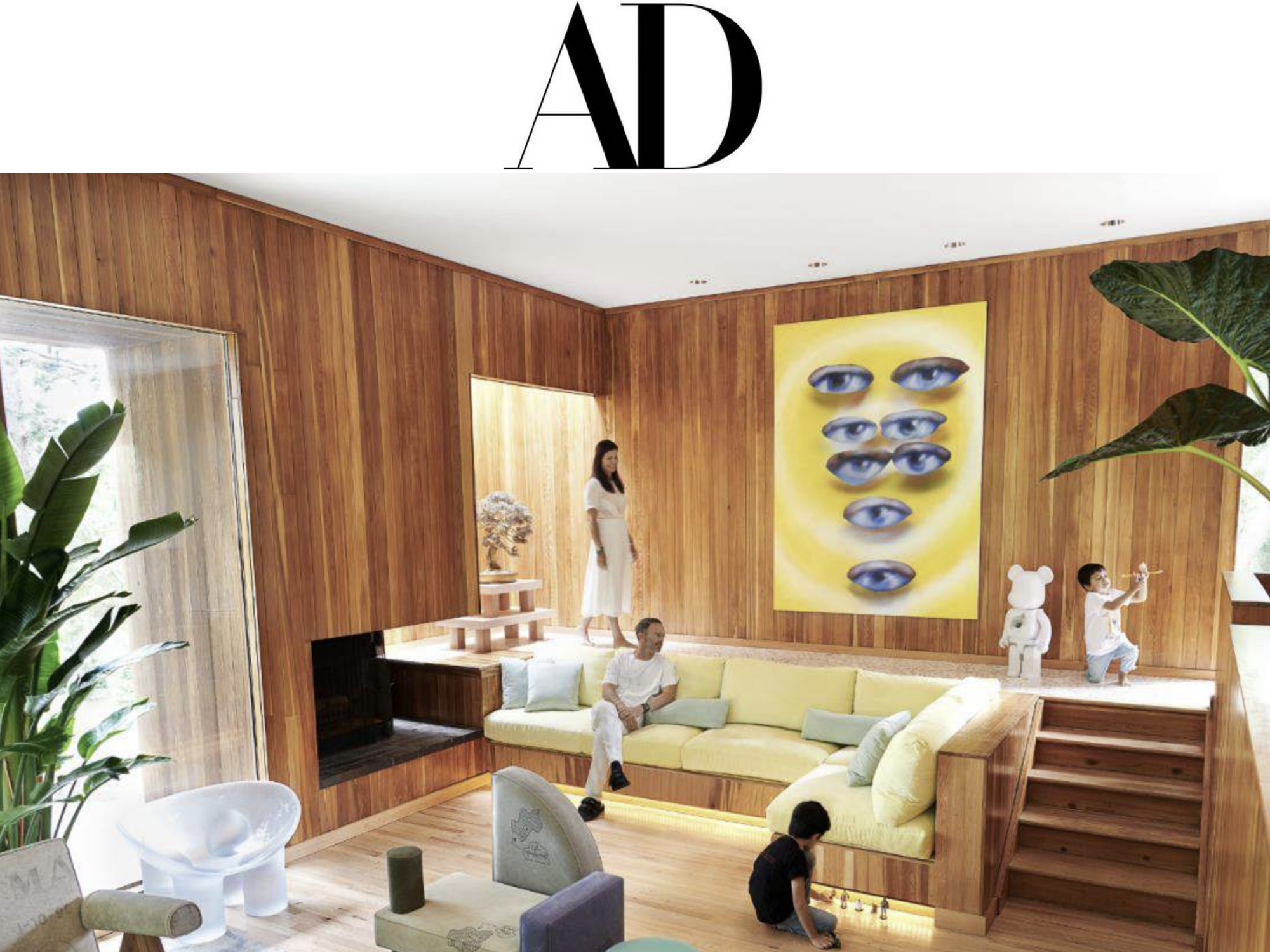

Given that architecture has always played such a prominent role in Arsham’s life and work, it appears seamless that his own private living space is a 1971 masterpiece by New York Five architect Norman Jaffe. Arsham’s search for a place outside New York City began a few years ago. He explains, “My wife, Stephanie, and I have two young boys [Casper, six, and Phoenix, three] and wanted a place to escape to. We had been going out to the Hamptons and loved being near the water, but I was originally looking for a piece of land that Snarkitecture would build on.”

Nothing came up, so Arsham created a Google alert for a few architects, including Jaffe. Shortly thereafter, Arsham received an alert for this house—one of Jaffe’s earliest—and drove out to see it the next day. About an hour from New York City, the compact house of approximately 2,200 square feet sits on a peninsula on the outskirts of a historic village on Long Island. “As I walked up the bridge to the entrance, I immediately knew how special this place was,” he says.

“When you look at it in the context of his larger body of work,” Arsham explains, “you can see how he was thinking and how his work evolved.” Jaffe would go on to build multiple residences on Long Island and his masterpiece, the Gates of the Grove synagogue in East Hampton.

There was tons of work to be done, and the project was driven to conserve as much as possible. Luckily, somehow all the original documents, photographs, drawings, and even personal notes by Jaffe about the finishes had managed to survive over the decades. The entire cedar interior was sanded to bring the wood back to its lighter surface and then sealed. Arsham did modify a few things: He replaced the slate tile in the kitchen and elevated walkway in the living room with a vintage-style terrazzo. He also redesigned the sofa in the sunken living room to make it deeper; as he explains, “My family wanted to use this space much more for lounging, so we created more depth and lowered it two inches . . . and we also added a movable ottoman so that all four of us can lie on it and watch Star Wars.”

The majority of the redesign focused on the master-bedroom suite. Arsham removed two bathrooms, a laundry room, and a bedroom to create a larger master bath and an office/gym. He points out that “Jaffe spent a lot of time in Japan after World War II, and this was a big influence on his entire practice. Stephanie is Japanese/French, and we incorporated many Japanese design elements and materials.”

Walking around the house, one is met with several pieces designed by Arsham and also in collaboration with Snarkitecture, which was involved at every level of detail of the renovation. The design stage took about five months and overlapped with the restoration, which lasted nine months from start to finish. Despite the demanding schedule of a global art star, Arsham and his family get out to the house most weekends and during the summer.

The house has even become something of a muse for Arsham. At Art Basel Miami Beach this month he will exhibit a project with Friedman Benda in which his recent work will be shown in a space that re-creates a combination of his living room and office. Reflecting on the house and the work that’s been done, Arsham wonders what Jaffe would think. “I think if he saw the house today, he would be pleased. Even though we’ve changed some things, we’ve stayed true to him.” Not an easy feat, two strong, singleminded talents collaborating together across time to conserve and bring new life to an iconic house.