By Kadish Morris

The designer on furniture, heritage and his new Pavilion of the African Diaspora at the London Design Biennale

Ini Archibong often begins work not with shapes but with sounds — homemade hiphop, to be precise. “Sometimes I don’t even sketch,” he says. “I’ll make an hour’s worth of beats and close my eyes. Those shapes I imagine become furniture pieces.”

Archibong seems to relish mixing things up. Since graduating in 2015, he has created a curvaceous watch for Hermès, a hand-sculpted table mirror for watch brand Vacheron Constantin and an interactive sound installation in Dallas. Still just 37, he has the kind of CV that many more established makers would envy. His poetic, mystical designs reference everything from his Nigerian heritage to philosophy, fantasy stories, mathematics and music.

For a while, he juggled music-making and design, but he decided to put his energy into the latter. “I knew that I could always make music, even if I didn’t have an audience,” he says, speaking via Zoom on a train to Geneva from Neuchâtel, where he is based.

The project now occupying his attention is arguably his most ambitious yet. It begins with a commission for this month’s London Design Biennale, the Pavilion of the African Diaspora, a temporary “folly” created in collaboration with architect Zena Howard from Perkins+Will. Sail-like in shape, the billowing structure evokes the ships that carried enslaved African people to America and the Caribbean. Installed on the terrace of Somerset House, it will act as a stage for talks and events celebrating African identity.

The pavilion will tell “the story of our people”, Archibong says: a “monument” to those from the African diaspora, as well as a testament to their global influence: “[It’s] a place that represents them. It’s also a physical space for them to express themselves to each other and for other people to bear witness to our dialogues.”

Project organiser Tamara Houston compares Archibong’s creativity with the Africandiaspora itself, “layered and complex with no single form of language”. His vision and work “always elevate the spirit”, she says.

Those supporting and advising on the project include musician Nile Rodgers,choreographer Robert Battle and museum directors Monetta White and Franklin Sirmans — a wide spread of talent from different disciplines and different places, all of whom have roots in Africa.

After the biennale, the pavilion will travel this autumn to New York, where it is scheduled to go on display alongside another new piece, “The Wave”. The project willcome to a climax in Miami at Art Basel in December, when these structures will be. joined by a third, this time in the shape of a conch shell. The horn-like shape of the conch is a central metaphor for the project, Archibong explains: the idea is to summon people from across the African diaspora to assemble, as well as amplifying and broadcasting the creativity of people of African descent. “This particular project is thinking about resonance and voices,” he says.

Archibong’s engineer father and computer-scientist mother emigrated from Nigeria to the US before he was born but, growing up in Pasadena in suburban southern California, he was immersed in a strong Nigerian community. “Both of my grandmothers came from our village and lived with us the entire time I was growingup,” he says. “My house was full of Nigerian artefacts. On the weekends, we’d go to church and dress in traditional clothes. We kind of led this double life as Nigerians. and as black American kids.”

A design career wasn’t exactly on the cards: his family expected him to get a solid education, then a steady job. “I’m Nigerian. I’m supposed to be an engineer or a doctor,” he laughs.

He started at business school before dropping out and applying for a scholarship to Pasadena’s ArtCenter College. It wasn’t until he graduated that his parents came round to his career choice: “When they saw how other people reacted to my work,they were like, ‘Wow, this is really something.’

A stint in Singapore with Tim Kobe’s collective Eight Inc, perhaps best known for developing the original concept for the Apple Store, came next, followed by a masters in luxury design in Lausanne.

Switzerland is now home — Archibong’s studio is here, and it’s where his daughter was born in 2017. “It never crossed my mind growing up that I would ever live on a lake with mountains behind me and trees at my window,” he says. “It’s like a postcard.”

His breakthrough was the collection he debuted at Milan Design Week in 2016. It was sponsored by the actor Terry Crews, who first met Archibong while the designer was working in a menswear store in his twenties and who has kept a close eye on his career.

The collection, created in collaboration with Crews’ Amen & Amen design house, was entitled “In the Secret Garden”. It looked both luxurious and alluringly futuristic, consisting of slender, hand-carved marble tables balancing on pink-and-blue glass legs, a glittering chandelier of crystalline lampshades resembling flowers and a brilliant white sofa whose underside was covered in vibrant west African batik print.

But it was the stories behind these pieces that made them stand out: the Galilee table. “represented the belief in self as a conduit of the power of God”, Archibong explains, while the chandelier was inspired by CS Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and the sofa by the Cheshire Cat in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. (Squint and you can see that it’s in the shape of a grin, with the backrests two large eyes.)

“When I design and create, I do it in a natural way. I don’t overly plan. I try to do it from my gut”

More recent projects have included the equally experimental “Below the Heavens” collection for the furniture brand Sé in 2018, which featured pastel-hued sculptural furniture inspired by the monolithic shapes of standing stones, crafted from marble and brass. Another collection, showcased at last year’s London Design Festival, references the post-volcanic landscape of the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland, with a wooden table and benches painted emerald green; they were supported by blocky hexagonal structures resembling columns of basalt.

Yoruba belief systems, which developed in what is now Nigeria, have been a powerful wellspring for Archibong. His curving white “Oshun” sofa is named after the orisha (guiding spirit) of fertility; a wallpaper design coloured the serene blue of Lake Neuchâtel near his home is called “Yemoja”, after a water spirit who is the patron saint of rivers. “I’m trying to capture [the orishas’] spirit and their energy,” he says.

Sometimes his mystical, kaleidoscopic pieces seem more like art or sculpture than homeware. As he points out, “In luxury, the function of an object is important, but it’s not more important than how it makes you feel.”

He prefers to follow instinct, creating forms that are then drafted on paper by his design team, before doing virtual 3D modelling himself (a skill he developed as a teenager). “When I design and create, I do it in a natural way. I don’t overly plan. I try to do it from my gut,” he says. Final fabrication in marble and glass is done by skilled craftspeople.

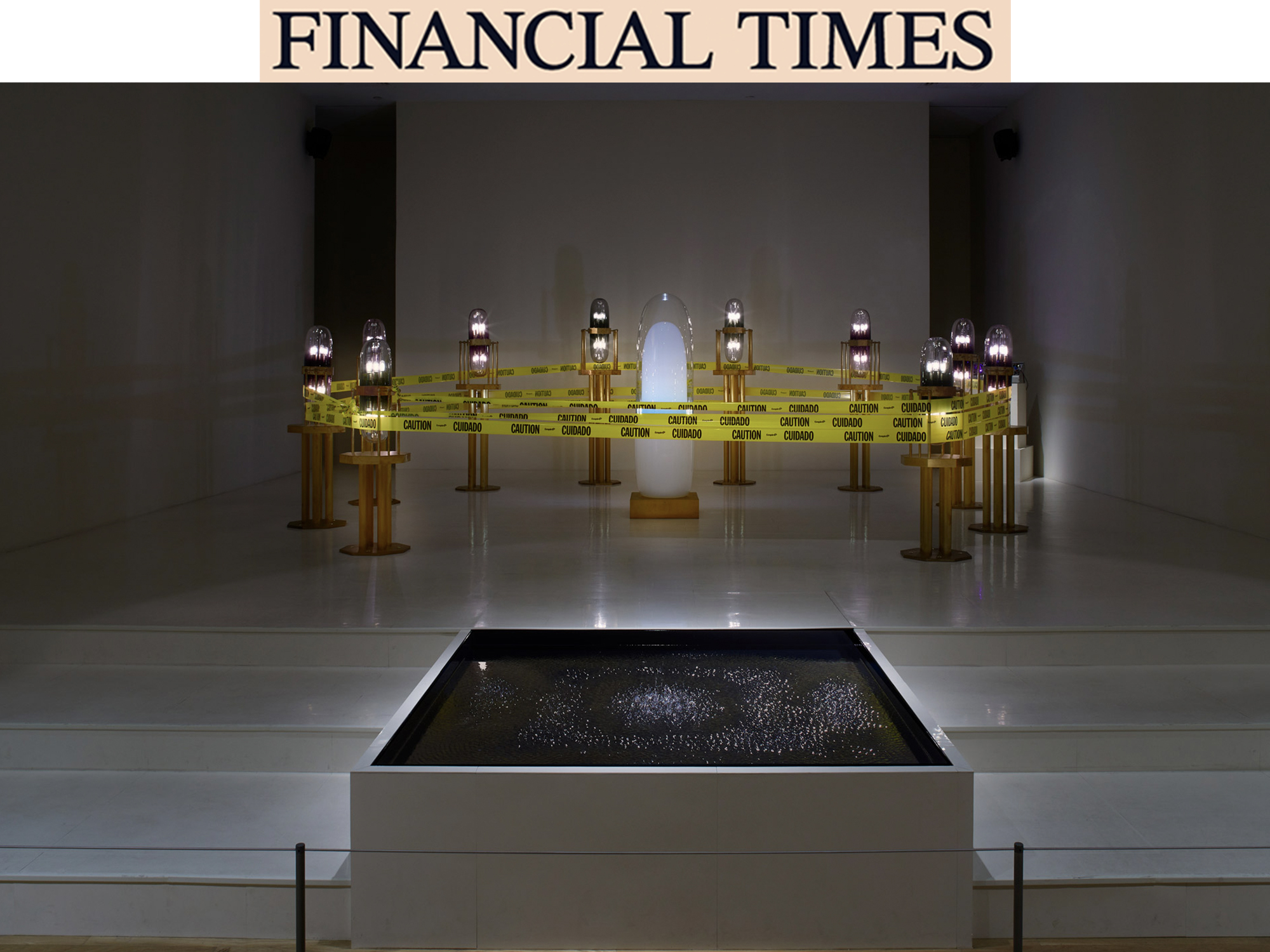

In November 2019, he installed a piece called “Theoracle” at Dallas Art Museum — a celestial installation made up of 10 capsule-shaped glass bulbs encircling a curved white obelisk, all set behind a black pool filled with water. In the original design, visitors were encouraged to interact: if you placed your hands on the bulbs, they turned out to be synthesisers that created sounds, which in turn made the surface of the water vibrate and shimmer.

After the Black Lives Matter protests last summer, Archibong “updated” the piece to protest violence against black people, covering it with yellow caution tape that prevented visitors from getting too close.

“It’s my only work that’s directly about what we experienced in America,” he says. “Putting the caution tape is basically saying: no one’s allowed to touch it until further notice. If you guys aren’t going to play fair, I’m going to take my ball and go home.” It is now in the museum’s permanent collection.

He feels no desire to return to the US: “People that didn’t grow up having a black experience in America, they underestimate what that does to somebody’s psyche,” he says. “I was 29 years old when I moved to Singapore, and within a matter of three to six months I woke up and I realised that I didn’t really have any imminent threat.”

He is keenly aware of his own status as an expatriate African-American designer working in an industry that, for all its global reach, remains overwhelmingly white. Research done in 2020 shows that among 4,417 furniture collections from leading brands such as Ligne Roset, Knoll and Cappellini, only 14 collaborations were with black designers. Although names such as Stephen Burks, Kesha Franklin and Jomo Tariku are becoming better known, there is intense pressure among the black

designers who have developed profiles to create a certain kind of career, says Archibong. “Can I be a black designer that’s not a celebrity?” he asks. “It’s never really been looked at as a place for us,” he says. “I didn’t have people to necessarily reference or model myself after that looked like me in the design industry. So, because of that, I created my own version of success. I want to lead by example.” But it’s also important for him simply to be himself, he adds: “As a black man in design, it’s important for me to show up as me.”

Archibong’s next big project is his first solo show at New York gallery Friedman Benda this autumn, where he will debut a dozen or so original pieces. “There’s also a bunch of secret stuff that we can’t talk about yet,” he says.

Then we’re back to music. Archibong is talking about his plans to have a DJ at the London opening of the Pavilion of the African Diaspora. “There’s going to be a lot of sounds,” he says. Maybe some pieces of his own music too? “No, no, no,” he says, suddenly shy. “I keep those under wraps.”

The Pavilion of the African Diaspora is part of London Design Biennale at Somerset House, London, from June 1-27; londondesignbiennale.com

This article has been updated to reflect that Nile Rodgers, Robert Battle, Monetta White and Franklin Sirmans are supporting the pavilion, not appearing at it; that the Below the Heavens collection referred to came out in 2018, not 2019; and that Archibong’s masters came after his time with Eight Inc, not before.

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first.