Designer Simone Farresin discusses SuperWire, his studio’s lighting collection for Flos, as well as an upcoming show at Friedman Benda Gallery.

By Eric Mutrie

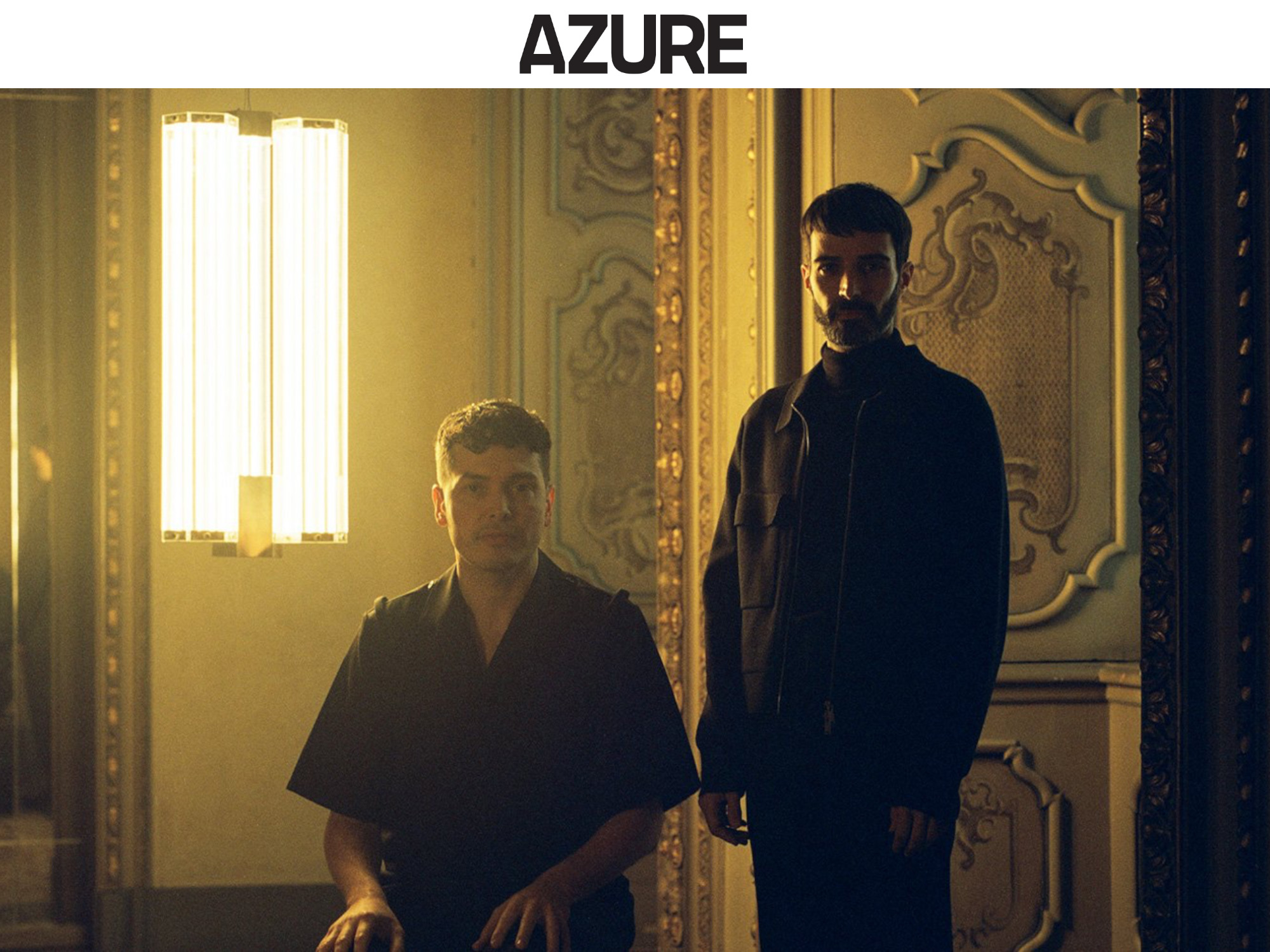

It is rare that we get to congratulate a designer in person for earning a spot on our annual Best Products of the Year list. But when I walked into the collector’s lounge at Design Miami last Thursday, I came face to face with Simone Farresin — one half (alongside Andrea Trimarchi) of Formafantasma, the prolific Italian design duo behind Flos’s new SuperWire lighting. After debuting the collection during Milan Design Week this April, Flos was previewing it at Design Miami ahead of an upcoming North American launch next year. In return, I gave Farresin a preview, too — letting him know that the collection would be announced as one of AZURE’s 2024 favourites on our website the day after we spoke.

Once he’d shared his gratitude for this accolade (the latest in a long list of achievements), I was eager to hear more about how exactly the lighting had come to be. SuperWire also struck me as an especially appropriate collection to be displaying at Design Miami, since it’s a family of designs that felt every bit as daring as much of what was being shown by the fair’s gallery exhibitors. And much like an original Flos Arco lamp from the 1960s, a 2024 edition of the SuperWire chandelier seems destined to one day fetch a pretty penny on 1stDibs (especially since the collection’s replaceable LEDs ensures that it is here for a long time, not just a good time).

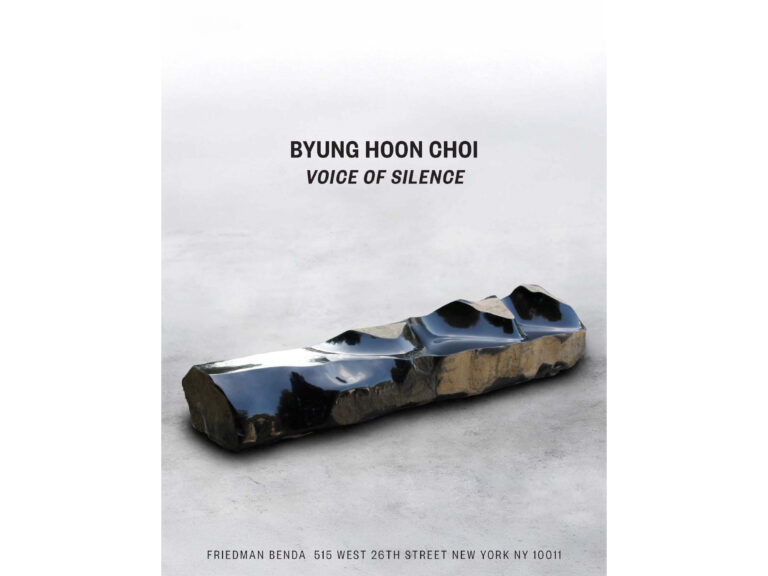

Formafantasma knows a thing about the collectible market, too: At the end of November, the New York design gallery Friedman Benda announced that it was now representing the studio. At its Design Miami booth, the gallery showcased Robo Lamp: a Z-shaped ash wood light that riffs on office lighting archetypes. More limited-edition conceptual works are set to follow, with Formafantasma slated to lead a solo show at Friedman Benda in 2025.

Below, Simone Farresin [SF] shares his perspective on both of these recent Formafantasma lighting designs — and where the core design industry and collectible design market intersect and diverge.

SuperWire for Flos

Photo by Robert Rieger

SuperWire is your third collaboration with Flos after WireRing and Wireline. How important was it that “wire” be part of the name of this product, too?

SF: I think it was important, actually, because it’s the continuation of a lineage. At one point, we had been thinking about a completely different name, but then we realized that these lights are also made of wires, in a way: The LED strips inside are extremely wire-like. So we thought, ok, let’s go with SuperWire.

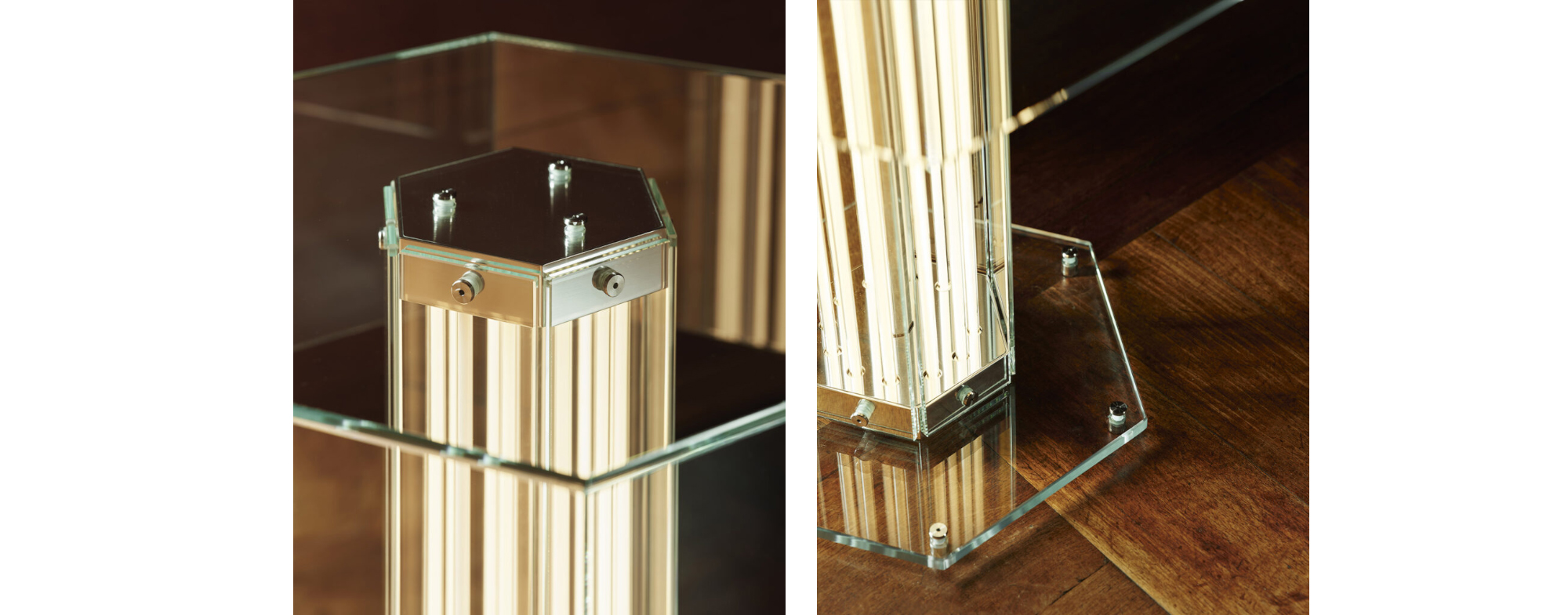

The collection’s core module is a glass hexagon with six thin LED strips suspended vertically within. What was the eureka moment where you came up with that configuration?

With LED light bulbs, we see a new technology being used to imitate something else. We thought, here’s a chance to design a new light bulb of our own — a new kind of light module. Back when we had been developing the glass element for WireLine, we had tried different ways of illuminating it to see if the glass would become more or less interesting. During that process, we were testing out LED filaments and became completely fascinated by them. Sometimes you just see something that you are intuitively attracted to. In SuperWire, the filament is enclosed within glass tubes, but when you have it in hand, it’s really spaghetti-like, so we felt there was great potential in it.

There is a lot of technical beauty in the construction of the lamps, and the design really showcases that. But how did you work to also balance that technical beauty with aesthetic beauty?

There’s several things that contribute to the design of something. The development of the module is really based on technology. But we are also admirers of the beautiful combinations of glass and lighting — thinking back to historical works of Max Ingrand in the early part of the century in particular. We thought that the dynamic between new technology and beautiful glass still felt very relevant, so we combined the two things. I like that people might not know all this, and just look at it and see that it’s good looking and has a lot of personality, but at the same time appreciate that it is carefully conceived.

Part of the care that you’ve taken in developing the lamp is working to ensure that it can be easily repaired if it breaks or when its LEDs reach the end of their lifespan. You’ve always been concerned with sustainability. What role does repairability need to play in that conversation?

LED waste is horrible. We recognize that, even with some of the pieces that we have designed, it’s impossible to get them repaired. So the problem of electronic waste recycling has been in the back of our mind. I also hate the idea that having certain kinds of ethics means needing to look like a hippie. So we were already doing more research-based projects into this, but Flos was determined to actually apply it to the industry. They really drove that push for repairability and replacement parts. And along with being able to replace the LEDs, it was also important to still use the right materials. We worked with clear glass because it is the most easily recyclable glass, as well as aluminum, because it is the most recyclable metal.

Do you think that the issue of LED modules that can’t be easily serviced or replaced is something that consumers are becoming more aware of?

Once something breaks, people are pissed. If they can repair it, they are happy. If they can’t, then they are even more pissed. So I don’t think people will necessarily buy this light because it can be fixed, but when it breaks and the instructions tell them to remove the glass and just buy a new filament, they’ll be a happy customer. We all know that it is problematic when things are not repairable. As more people realize that, I think that there will probably be a resurgence of designs that use LED light bulbs, because that format is easy to replace. But this is our way of proving that you can do something else and still make it repairable, too.

Photo by Robert Rieger

The design showcases its screws very prominently (and elegantly). Is that a way of reflecting that the design is user-serviceable?

Yes, it’s all part of the same concept. You have screws because you can open it, and so we wanted to show them to communicate that. Once when we were working with a Scandinavian company, they pushed us to try to remove as much as possible to make the design “clean.” The iPhone is like that — it’s this extremely mysterious object that looks like the monolith from 2001 — A Space Odyssey. It’s supposed to convince you that it’s extremely intelligent. But for me, there is a pleasure in understanding the construction of something. It’s a certain type of clarity — a philosophical transparency — that comes when the object in front of you is explaining how it is made in an intuitive way.

Once you had the design of the core module in place, how did you go about adapting it for the different types of lights in the collection? Tell me about the symbolic shade around the table lamp, for instance.

Actually, we tried it without that, but it felt too radical. I keep mentioning the iPhone, but when it was first invented, Steve Jobs — and I’m not saying we’re like Steve Jobs — said that it needed a button, because otherwise people don’t know how to interact with it. Then, after many years, they got rid of the button. This reminded me of that, because if you look at it as a table lamp without the shade, it just looks like a component. We needed to add that element to make it recognizable. It was important that when you look at these pieces, they feel extremely contemporary, but they also reference these past archetypes. With the table lamp, that meant going back to a traditional lampshade. With the floor lamp, that meant referencing the history of Flos with a base in the same style as the Castiglioni Luminator. All this familiarity is helpful — it helps people be more accepting of a new aesthetic.

The lights launched during Milan Design Week in a display that made great use of mirrors at Palazzo Visconti, the same venue where Flos had also exhibited 36 years ago. What did you like about that installation?

I think what was interesting about that exhibition by the Flos team that I really enjoyed is that it was about how our work was in conversation with other work. We tend to perceive the past as being situated far back. But in fact, in Italy, it’s not, really — it’s everywhere. So that presentation was about showing how things come together seamlessly —conversations between aesthetics, between realities, between ways of doing things. And I think that’s really beautiful and powerful.

What sort of reactions did you hear — during and after the launch, and here at Design Miami?

We have been really happy with the reaction. I think many people don’t immediately get the technical component, but we appreciate how they still engage with the pieces and have their own interpretations. Many people have called them retro-futurist, which is not something that we had been thinking of, but it is maybe something that we do intuitively — we like to reference character types from the past. People also ask how much it costs, because it has the look of a luxury design.

The collection will launch in North America in 2025, but the floor lamp currently retails for €4,700 in Europe. Was cost a factor during the design process? Was there any part of your initial vision that you had to alter to try to reach a certain price point?

No. And for that, I really love the process and the trust of Flos. At its core, Flos believes that if you have a great idea in front of you — especially one that will demonstrate something that Flos can do that other companies cannot — then you need to go for it, no matter what the price. Because the history of the company is making risk-taking objects. If you think back to the Flos Arco floor lamp — who would ever have produced such a bizarre object? Now, of course, we all know and love it — but in the 1960s, no one else would ever have accepted a gigantic design that’s 40 kilograms of marble. It’s completely groundbreaking. So a company with a history like that cannot limit the production of a product like this based on price point. That would be stupid.

Robo Lamp for Friedman Benda

Photos courtesy of Friedman Benda and Formafantasma

That leads us nicely into the collectible design market. Friedman Benda announced last month that you were joining the gallery’s roster. Here at Design Miami, you’re showing Robo Lamp. Tell me about the concept behind that design.

The light we presented with Friedman Benda is just one piece of a larger collection that we will unveil with the gallery next June. So in a way, for us, it is very strange to talk about a work that is not fully presented. For the show, we have been really discussing with [Friedman Benda Gallery co-owner] Marc Benda the idea of archetypes in design — so it is an exploration of many different kinds of archetypes. Looking at Robo Lamp, we worked with a contemporary lighting archetype: the LED panels that you can find in offices, which are a very cheap, banal form of lighting. Here, we have somehow freed those panels from the office to create an object that also reflects another office archetype: the adjustable table lamp, but on another level in a completely context.

How will the rest of your solo show at Friedman Benda build on that idea next year?

I think in some part, at least on a subliminal level, it’s about some of the aspects of American design that we really like. I’m thinking of the Shakers, but also Frank Lloyd Wright. This will be our first show in the United States, so we were really thinking about that — through the idea of extreme restraint and utilitarian design, and through materials like cherry. But we were also thinking about what kinds of new archetypes enter into interiors through contemporary domesticity. The show will also be about architects of domesticity, who are not very often celebrated — so one of the archetypes that we will explore will be embroidery. I know all this might sound abstract. It will be easier to talk about next year!

How do you see your work for the collectible design gallery market comparing to your work for commercial brands in the design industry? Do they satisfy different impulses?

Working with a gallery is an opportunity to explore ideas that sometimes could be executed within the industry, but very often could not — because you need to work with materials and technologies that perform in a very certain way. So a light like Robo Lamp is freeing us from some kinds of restrictions — but that does not necessarily mean exercising excessiveness. It was very important to us to make sure that the objects we are presenting with the gallery make enough sense that they can enter the lives of people without just being a sculpture. That is something that this work is really not doing. It is actually quite a sophisticated exercise in design restraint and interpretation.

We’re here in Miami — what do you like about the city’s design scene?

This is my first time in Miami! I know it sounds very cliché, but we are Art Deco lovers, and so many of the Art Deco buildings here are really fascinating to us. To be in a city that has such a concentration of Art Deco is extremely special and has really captivated me while I’ve been here.