By Y-Jean mun-Delsalle

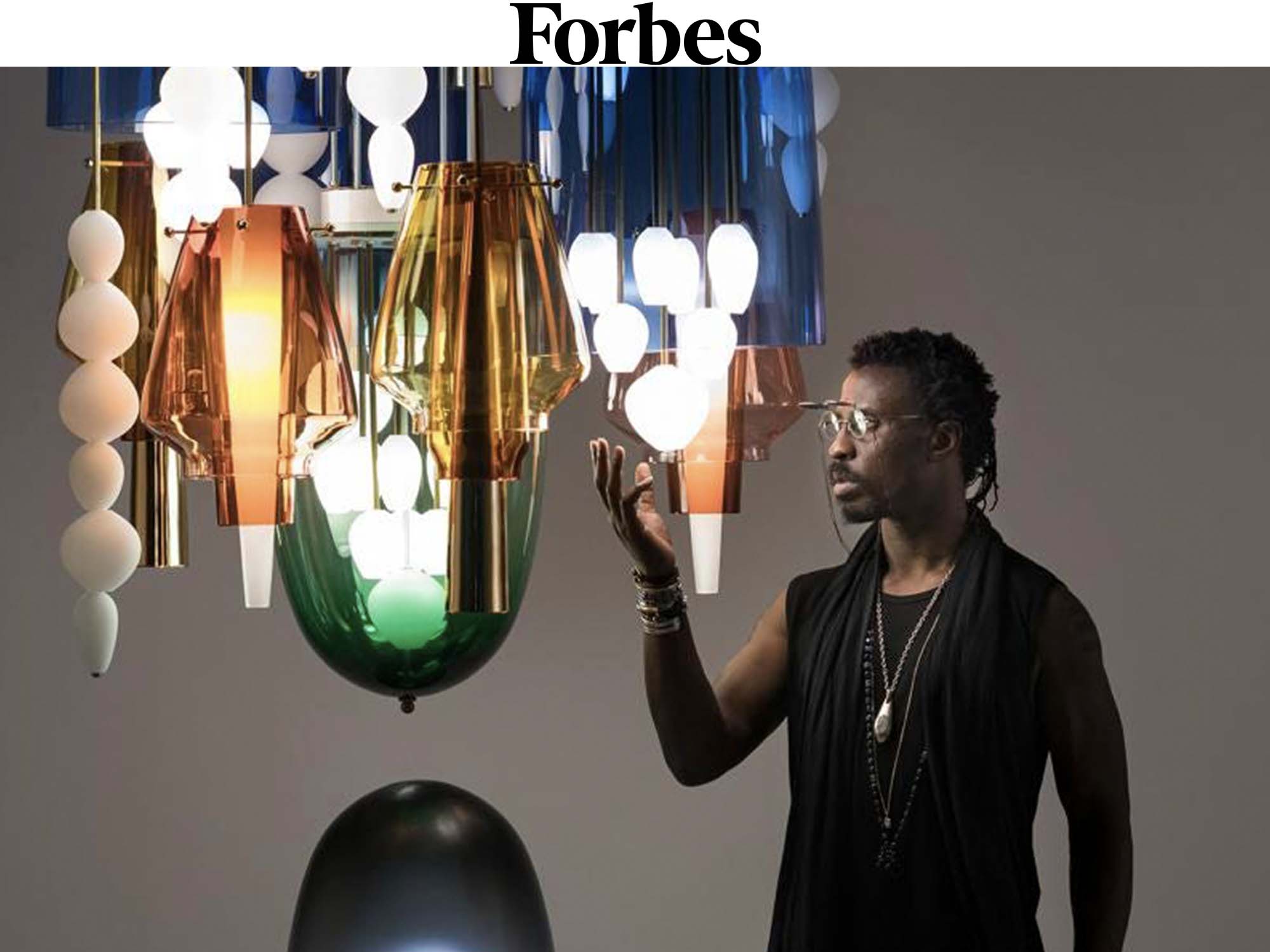

Switzerland-based, Nigerian-American designer Ini Archibong has produced collections with the likes of Hermès, Knoll, Sé, Bernhardt Design and Logitech and exhibited at The Met, Dallas Museum of Art and Friedman Benda. I sit down with him to discuss his beginnings and the path he took to design.

After graduating from ArtCenter College of Design in California, why did you go to work at Eight Inc. in Singapore?

Honestly, I was following a mentor of mine, Tim Kobe, who’s the founder of Eight Inc. I’d done internships at Eight Inc. in San Francisco and in New York because I’d developed a relationship with Tim while I was a student. When I graduated, he actually came to my graduation, and afterwards, he told me that he wanted me to come to Singapore to work with him on some projects. It was an adventure that I couldn’t say no to, I guess. I’d never been in Asia before. It was my first time living away from home internationally. I’d lived in different cities, but I’d never moved away from Southern California for a long period of time. I was in Singapore for about two and a half years. It was amazing.

What kind of projects did you work on in Singapore?

I mean most of it is kind of top secret, but it was primarily innovation around industrial design and technology. I was working directly with Tim Kobe himself and there wasn’t really a clearly defined department. I was like a multi-skilled lone sort of department, so Tim would come in and we would discuss interesting things that were going on that were on the cutting edge of technology, and then we would come up with solutions and I would design proposals, anything from an app or an architectural space to industrial product design. Then also because I’d studied environmental design and architecture and had worked as an intern in the other offices, I knew the Eight Inc. approach to experience design and brand and architecture, so whenever I was needed, I would also help the other departments, like the architecture department.

You consider technology to be something that becomes obsolete rather quickly, so you’d rather focus on making things that will last for generations?

It’s interesting because a lot of that state of mind and way of thinking developed because of me living in Singapore. It’s true that my goal was to have a lasting impact with the things that I was making, so it was a little bit frustrating that by the time anything gets made, we’re already thinking about the next thing. But also living in Singapore and experiencing the approach to luxury there made me start to think about luxury and to look at it in a different way. I don’t think that before that I was very much exposed to the experience of valuing luxury in the way that I saw when I was living in Singapore.

Why do you choose to live in Neuchâtel today?

There are multiple reasons. When I studied in Lausanne, I was already in Switzerland, so I just got accustomed to the way of life here. And I think it’s a truly special place. When I started doing projects within the watch industry, it made sense because I was coming from Basel and I was always coming out to Neuchâtel, Geneva and Biel. I decided to move to the lake to have a slower pace of life and be surrounded by nature rather than noisy cars. It’s just a better way for me to live, and also staying in Switzerland because I have a young daughter who was born here in Switzerland, and that also keeps me grounded.

Do you work alone in your studio or with other people?

I’ve always worked alone, but I now have a group of young, talented folks who are part of a collective. I don’t necessarily call it my studio. They not only support projects that I’m working on, but I support projects that they want to work on, and we’re trying to figure out a way to do something new and different. I have a studio inside my flat where I do most of my creative work, and then a few paces away, across the street, I have a studio where the L.M.N.O. creative crew is working. When we need to meet, we meet, but otherwise I still work pretty solitary.

When you need the expertise in a certain craft, you go to the place where they have the expertise?

Yeah, always. I think what has probably been very critical for my career is finding people and recognizing where the expertise lies and leaning on that. I think the biggest job that we have as a designer, artist or creative in any sense is to have the vision. The tools that I’ve cultivated even when I was making my own pieces, all of that leads to a better understanding of how to translate my idea to the experts who are going to be making and engineering it. Now the most important thing is that I’ve had enough experiences and I’ve tried enough things that I know how to translate my idea to people who are experts in doing whatever craft that they do. Otherwise it would be impossible for me to create these things.

You founded your own design studio in 2010 while still a student. What was your first design project?

It was the Serif table for Bernhardt Design. It’s still on sale. You can buy it. That was my entry into the profession. Before that, I was planning to graduate from ArtCenter and do a master’s in architecture and enter the realm of the lifetime architect. And then I designed that table, and it sent me in a different direction. I designed it in 2009 and 2010, and then 2011 was when it hit the market. I think it’s still one of their best-selling tables.

Were you trained in architecture?

I didn’t go to architecture school before ArtCenter, but my first mentor in architecture was a man named Tony George. After dropping out of business school, I started to fall in love with architecture. I started collecting architecture books. My favorites were Shigeru Ban, Tadao Ando and IM Pei. I was getting immersed in these books and drawing a lot. Then I walked into his architecture office and, within a few weeks, I was hired even though I didn’t have experience. He trained me in architecture for the next three years, drafting, being on construction sites, everything, and so I built my portfolio. Then when I went to ArtCenter, the program was actually environmental design, which is architecture from the inside out, more or less. It’s from the experience standpoint as opposed to just drawing architecture from the outside of the building. So I was trained professionally in architecture before I went to design school, and then I was studying mostly architectural things while I was at ArtCenter. I was planning to to do the master’s after that, but then I found love in the design of these smaller architectures that we call furniture.

Would you still want to construct a building?

Yeah, it’s still the plan. Last year, I did my largest constructed temporary space, the Pavilion of the African Diaspora. That’s kind of the beginning point of starting to move in that direction. I designed some interior spaces and soft architecture that hasn’t made it to the world yet. Maybe someday it will, but I haven’t entered the space of doing buildings yet.

Before you went to ArtCenter, what was the business school you attended?

I went to the University of Southern California on a presidential scholarship, and I was part of a group of students who had the opportunity to basically, from the age of 18, dedicate everything towards business with the goal of having a MBA by the time of leaving five years later. It was like a fast track. Most of the time, you go into your undergraduate and study a variety of things, and you select your major by the time you’re two years or three years in, but those of us who wanted to be business scholars made the decision upon entry that we would have these scholarships and have a schedule that was aimed directly towards coming out as businesspeople. I would have ended up with a degree from the Marshall School of Business if I’d stayed, but I dropped out very early.

What made you change your mind?

I would say it’s just life. It was one of those things where I think pretty early on, I started to question the trajectory of my life, what I was doing and what I was meant to be doing here on earth, and becoming a rich banker didn’t seem to match anymore. It made sense to my 17-year-old mind graduating from high school, but after being there for a year, I realized that my passions lay elsewhere and that I had a better way of being of service to the world, and essentially that I needed to follow that.

Tell me about wanting to be a musician at one point.

I still make music. There was a period of time after I dropped out, I didn’t immediately jump to architecture. I just knew that I needed to express myself creatively and I started looking at the things that I’d been doing my whole life. Those things were music and making things. That turned into taking music pretty seriously and connecting with a lot of musicians in the LA beats scene during that time. For a while, music was a major part of my career thinking. It was during the time that I was working for the architect that I was also making music, so I ended up having to make a decision about where I was going to dedicate my professional energies and what was just going to be something that I kept for myself. That’s when I decided to focus on design and let the music be more in the background.