By Judith Gura

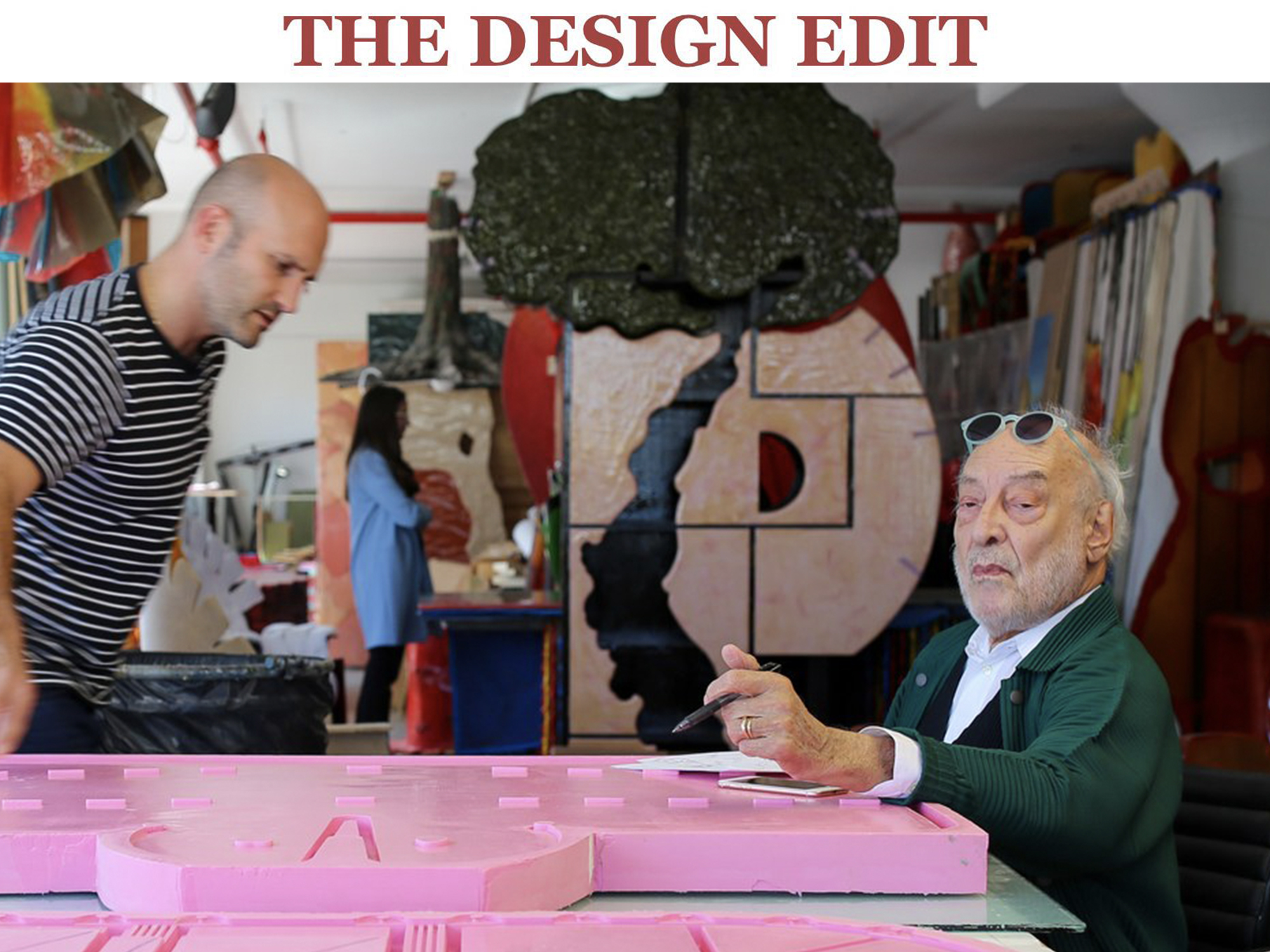

SOME OF THE most inventive furniture designs we’re likely to see this year are being generated in a busy, light-filled workshop in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Presiding over a handful of enthusiastic assistants, Gaetano Pesce is still shaking up the establishment, his energy and creativity undiluted after more than five decades of designing.

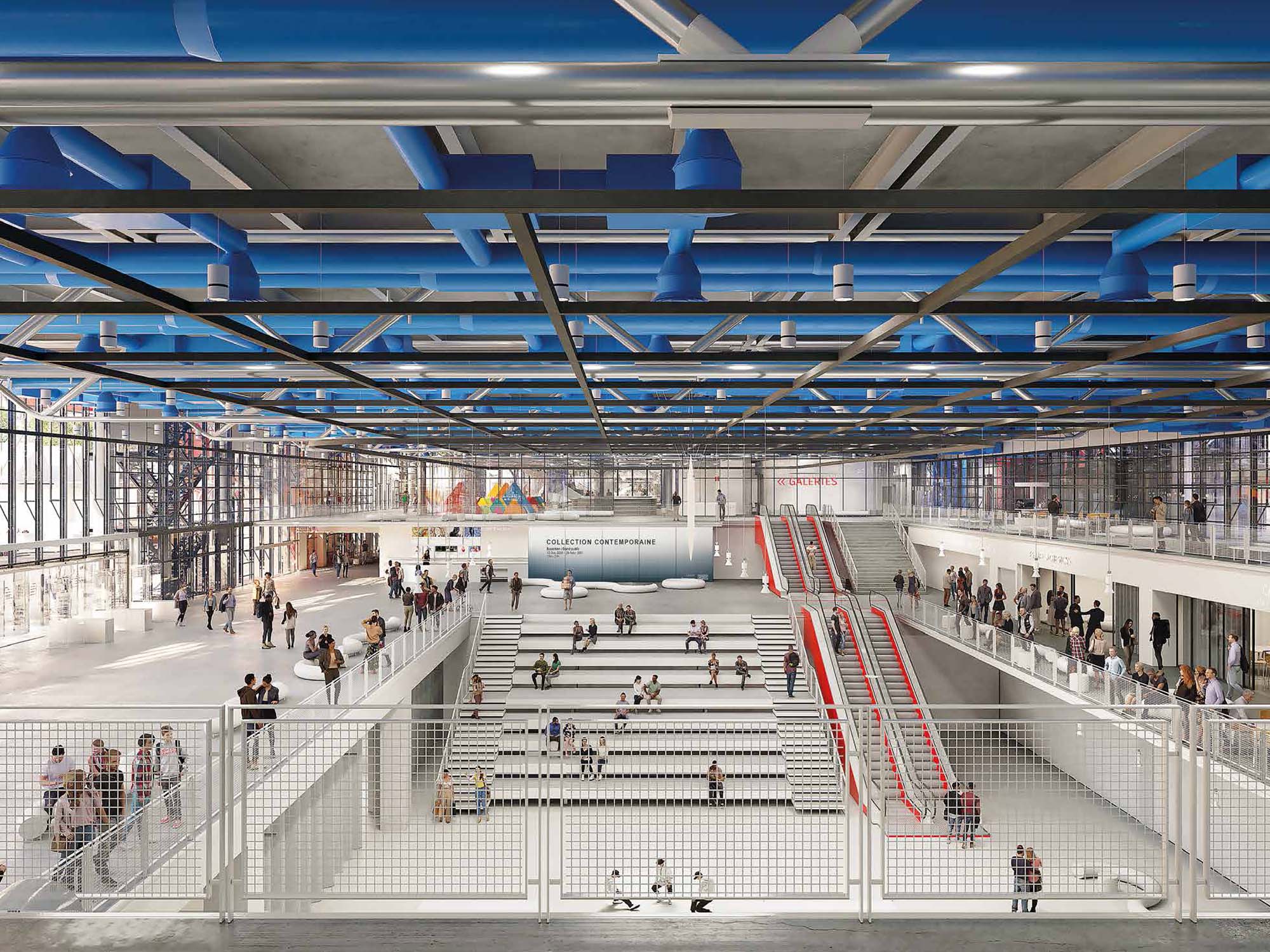

Visitors to New York will have the chance to see Pesce’s newest designs – as well as groundbreaking past work – in two Manhattan galleries this fall: on 24th October, Friedman Benda opened ‘Age of Contaminations’, a survey of Pesce’s work from 1968 to 1995, and the following day, Salon 94 debuted his new designs, and inaugurated a new gallery space by relocating the entire Pesce workshop for a week of on-site activity.

Born in La Spezia in 1939, Pesce graduated the University of Venice with a degree in architecture in 1965. He quickly gained notice for his individualistic, often witty designs, and started making waves in America with his contribution to the seminal 1972 exhibition ‘Italy: The New Domestic Landscape’ at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Instead of a product, he presented an “underground city”, a fictionalised archaeological study of a 2000 BCE habitat, which he described as “a commentary, not a design.” It was the most talked-about element of the show. A few years later, MoMA gave him carte blanche to research architecture for a one-man show in its Goodwin Gallery though, he recalls, “It was where only dead people showed … and I was just 35!”

At the time Pesce was living in Paris – after brief residencies in London and Helsinki – but in 1980 he moved to New York. “It was the capital of the 20th century, and it’s now the capital of the 21st. Living in New York, you learn where our time is going.”

And how does he think it’s going? Architecturally, not so well: “Most of the work we call architecture is just building,” he says, noting that some of the most-lauded architects of our time (he mentioned two names that are not repeated here) are just doing the same thing over and over. To him, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum is the only real piece of architecture in the city: “It has a dialogue with the rectilinearity of Manhattan.” Though trained in the profession, Pesce has not focused on architecture, explaining, “It’s important to be multidisciplinary … otherwise you repeat the same thing. So I just jump from one thing to another.” Over the years, the jumps have taken him to design a variety of products, interiors, and urban plans as well as buildings.

But his best known, and most innovative, work has been in furniture design, which has included work for major manufacturers as well as experimental pieces. His most popular design is the ‘Up’ chair from 1969, for which he adopted the characteristics of a sponge to a bulbous seat that, when vacuum-packed, compresses to fit into a 3” high shipping carton, and expands to full size when unpacked. He is proud of the innovative technology, though the chair became an international sensation primarily for its provocative look: the shape evoked a female form, and was tethered to a ball-shaped footrest, symbolising the constraints placed on women. The 50th anniversary of this icon of Italian modern design was celebrated with an 80-metre-high replica, installed in the Piazza del Duomo in the centre of Milan.

Pesce takes particular pride in the ‘Pratt’ chair series, from 1984. “To make a chair is a very complicated thing … it is an element through which you can express a lot.” When Pratt Institute offered him use of their laboratory facilities to make a chair, it gave him the opportunity to experiment with resin. “I was lucky, as the first to study this material.” He explains that, since his classes in materials had included “nothing from today,” he had approached chemical producers, asking to visit and learn about their products. “I saw incredible things I never knew existed,” he remembers. Offered the new plastics to work with, he came up with the idea of mixing varying densities of resin and pouring them into the same mould to make nine successive versions of the same chair form. The first chair collapsed, the next fell over when touched, and succeeding versions had gradually more structure, until the last was like a rigid sculpture. “It was between art and design – for me, it was a very important project.”

The line between art and design, he believes, is flexible, and can change according to the occasion. He recalls arriving at a party years ago at Peggy Guggenheim’s home in Venice, when he and his wife were greeted by an attendant who took their coats and hung them on a nearby Giacometti sculpture. “The Giacometti was art in the morning, a hanger in the evening … depending on the moment, a piece can be art or design.”

Since the ‘Pratt’ chairs, Pesce has embraced the unexpected, working with materials like polyurethane and poured resin, which yield results that are often unpredictable. “If you’re sincere as a creative person, you use something of your time – this is of my time.” Though unquestionably of the time, even his most unusual designs are meant to communicate. For that reason, he likes to use figurative images. “When you use a form they can recognise, people can respond. They can say they like or don’t like it – whatever they think. It’s a much richer exchange.” It’s also considerate: “In our job there’s a mission to make people have a positive feeling … to give pleasure to people looking at something.”

Though he’s obviously enjoying himself, Pesce takes design very seriously, complaining that “The New York Times still considers design as decoration. But design is a discipline.” Each of his designs is carefully thought out before fabrication begins. “I make a model, or a drawing, or I describe what I want – which is sometimes better.” He shows a visitor plywood models of pieces now in preparation: a bookcase, one side of which is the designer’s profile; and a massive secretary cabinet whose segmented round front opens by remote control. For a manufacturer client – like a piece being designed for Cassina – the model is larger. “We don’t give a company a drawing, we give them something they can sit on.”

Though he follows no specific style, Pesce’s work is generally easy to identify. It’s made of modern materials, it usually conveys an idea, and it doesn’t look like anything else of its type. As he says, “I don’t like to do something that someone else has made already.”