By Charlotte Abrahams

I HAD INTENDED to interview the British artist Faye Toogood in London, in the sliver of a Victorian townhouse she converted into a studio four years ago. But, in the few days between making the arrangements and our actual meeting date, everything changed. Lockdown shut us both in our homes, closed New York’s Friedman Benda gallery which represents her and confined the collection she was due to exhibit there to a storage warehouse.

“It’s weird,” she says when we speak on the telephone, “at the time I was making this collection, I was reacting to what was happening in my own life – I’d just had my twins – and I felt there was a need for the new work to have a strong sense of vulnerability. Now coronavirus has given that vulnerability a new context. It feels very timely.” The new work she is referring to is Assemblage No 6: Unlearning, a collection of furniture pieces, each of which is a scaled-up replica of its original maquette. They look fragile and precarious. “I have always made maquettes,” Toogood says, “but often by the time you get through the sampling, the magic has gone. This time, as a result of watching my young children begin to make things and seeing the purity of that making, I wanted to see if I could get from the maquette to the final piece while retaining the charm and naivety of the original. That was the challenge I set the manufacturers I work with. We failed at Sellotape, but the cardboard was a triumph.”

It certainly is: ‘Maquette 16/ Box Stool’ is made from cast bronze, but it has been painted to look so like a, slightly crumpled, pile of cardboard held together with masking tape that you have to reach out and touch it to actually believe in its functional stability. Toogood and her craftspeople had similar successes with paper, recreating the delicacy of a sofa maquette in primed washed canvas and fabric paint, and also with wire. “I had a wire and card maquette of a chair that really made me smile,” she says. “I wanted it to be part of the final collection and eventually, I found someone who could capture its wobbly, misshapen form in ironwork and bronze.”

Friedman Benda Gallery’s founder, Marc Benda describes Assemblage No. 6 as “a leap of faith” for the artist. “She has done away with the three starting points that you normally see with designers: process, typology and material,” he says, “and in so doing has completely up-ended the design process.”

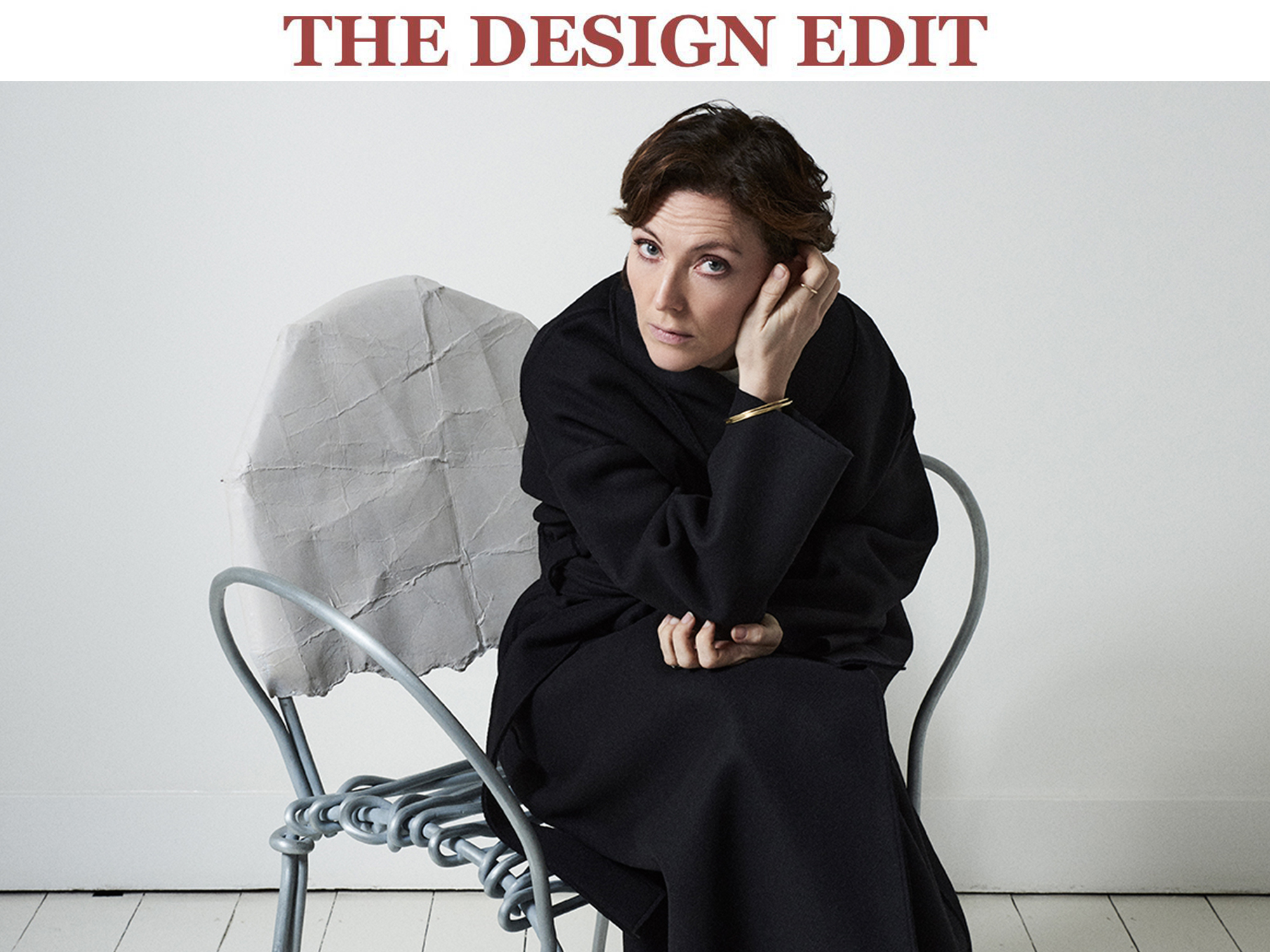

Disrupting traditional ways of thinking and making are Faye Toogood trademarks. The 43-year-old is a rebel, but her rule-breaking is largely the result of a background that has left her without “the foggiest clue how I’m supposed to be doing things.”

Toogood grew up “in the middle of nowhere”, the daughter of parents who believed in foraging, making and gender neutrality. “My sister and I spent endless days out in the English countryside,” she says. “I was a tinkerer, collecting rocks, sticks and bones. I now realise that experience is fundamental to the way I approach materials and colours and organise things in my head.”

A trip to Barbara Hepworth’s studio and gallery in St Ives when she was eight convinced her that she wanted to be an artist, but she took an academic route when she left school, studying History of Art at Bristol University. She then landed a job at World of Interiors, having turned up to her interview with the magazine’s then editor Min Hogg with a box of sticks and bones. “My time there was the most incredible education in objects, furniture, space and the way we look at things,” she says. “I went to castles in Sweden, beautiful temples in Rajasthan and mud huts in Mali. I handled 16th century teapots and contemporary furniture. I created sets.”

Eventually, however, she became frustrated by the limitations of making disposable interiors for the flat page and so, in 2008, she set up Studio Toogood in order to explore more permanent, three-dimensional ways of working. Her first commission, from fashion brand Comme des Garçons, was for a shoe display area in the basement of Dover Street Market’s London store. Consisting of stacked white plaster blocks and interlocking copper pipes set against rough rendered concrete walls, it was a template for a material-driven aesthetic which, a year later, informed her first series of design objects.

Driven by her desire to emphasise the nature of her chosen raw materials – wood, brass and stone – Toogood chose the simplest of shapes. She made a coffee table by placing a sheet of glass on top of a hand-turned solid-brass tube, a hand-turned sycamore sphere and a honed Perryfield whitbed Portland stone cube. She made a chair from a three-legged milking stool and a spade handle. ‘Element Table’ and ‘Spade Chair’ have both become design classics recognised by major museums around the world. At the time, however, Toogood was simply following her instincts and was so wary of the design world that she called this series of objects an ‘Assemblage’ rather than a collection.

“It was the London Design Festival, the time when all the ‘proper’ designers launch their collections,” she explains. “I felt like the fraud in the room, so I decided I needed to acknowledge that I wasn’t a designer. What I was, was a stylist, an interiors person and a set designer – that meant I was very good at editing and shaping existing materials and forms and making them into something new. At assembling things in other words.”

The term has stuck and, while each of the five Assemblages she has launched in the decade since has been enthusiastically received by the design community, Toogood still sees herself as something of an outsider. “I am a designer because I am interested in the brief, the client, the budget and how people live, but I am not a designer who you go to with a practical problem that needs to be solved,” she says. “The importance of design is not just solving problems, it’s also how we feel and that’s why I do what I do. I like it when someone sits on one of my chairs and something happens.”

How she feels herself is often the starting point for her work. Each Assemblage has been prompted by a shift in her own life. Assemblage No. 4, for example, came after the birth of her first daughter. Subtitled ‘Roly-Poly’, it embraced a world of soft lines and childlike rounded edges, imbuing her characteristic interplay of geometric elements with reassuring plumpness. There was a day bed with a spherical headrest, the combination reminiscent of a reclining pregnant woman; a chair whose chunky cylindrical legs and embracing semicircle of a seat made it an immediate favourite with design-conscious new parents, and a new iteration of the ‘Element Table’. Gone were the sharp angles and familiar square, sphere, cylinder, and in their place came a soft-edged solid bearing three, smoothly hollowed out voids.

Toogood frequently revisits existing designs. She is not interested in trends or newness for newness sake, focusing instead on what she calls her “three pillars” – sculpture and form, geometry and landscape – and the way in which her chosen material informs the form. There are six iterations of the ‘Element Table’, including the simple glass, stone, brass and sycamore original and the sleekly polished crystal resin version she made for Assemblage No. 2. And, having created the ‘Roly-Poly Chair’ in fibreglass for Assemblage No. 4 in 2014, she made it again two years later in cob composite, sand-cast bronze and lithium-barium crystal. In the latter, this chunky chair, so big it is almost lumpen, looks light as water. Try to lift it, however, and you discover that lithium-barium crystal is heavy. Really heavy. This contrast between what is, and what seems to be, is a feature of all her work and it is intriguing.

Assemblage No. 6 is Toogood’s most intriguing collection to date. The trompe-l’oeil effects imitating the twisted wires and taped cardboard of the original models, preserve the creative steps that led to their genesis while simultaneously disguising the true materials of their construction. Those true materials are precious, made to look commonplace by the finest of craftspeople. It is, as Marc Benda says, a body of work that upends all expectations. Except one: Toogood’s work has always told stories. Assemblage No. 6’s story is about the purity and joy of making and the push-pull between fragility and strength, the refined and the ordinary. In these uncertain times, that’s one we can all respond to.