By Andrew Gardner

Sculptor and furniture designer Jonathan Trayte, a native of Yorkshire, UK, spent his early childhood in a camper van with his family in rural southern South Africa. Back in the UK, his childhood was filled with weekend picnics in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, sparking his love for sculpture. He went to Canterbury for his BFA and worked in kitchens on the side, a job that continues to influence his work today. Jonathan graduated from the Royal Academy in Art and was quickly met with success around his bronze sculptures but was itching to experiment more. And experiment he certainly has – from collaborating with Kit Neale on a café commissioned by the British Fashion Council to creating a desert road-trip inspired show at Friedman Benda, he melds together materials, concepts, and memories to create exceptional works of art.

What is your earliest memory?

The baboons in South Africa. We grew up on the perimeter of the Kruger National Park and they would come over the fence to steal food, or anything really, they were having fun. My mum would just grab us and run, we would have to wait out on the dirt track whilst they raided the kitchen. There isn’t much you can do when a baboon wants what is in your fridge…

How do you feel about democratic design?

This is tricky, I feel two ways. If democratic design means accessibility then yes, people should be able to improve their living standards despite their socio-economic footing. But in reality I think this means IKEA and endless generic chipboard units. The waste we produce as a species is appalling, as a maker I continually feel conflicted. Also, in the leveling of design standards, we lose the delightful nuances that come about through cultural differences and generations of problem solving. I cherish the weird and wonky hand-me-downs and homemade gifts far more than anything that money could buy.

What’s the best advice that you’ve ever gotten?

‘Work on the edges and the middle takes care of itself’. The foreman at the foundry told me this when we were scaling up an enormous Barry Flanigan sculpture, it made me laugh. In reality though it’s probably this; ‘don’t let a bad decision you made yesterday affect how you go forwards today’. I interpret this as ‘always question everything and challenge yourself constantly’.

How do you record your ideas?

I’m always drawing, even just scribbles in a sketchbook are really important. I travel a lot too, sometimes cycle touring across entire countries and wild camping en route. I’ll take tons of pictures but will also stop and draw often, it’s amazing what you see on the road or up some remote mountain track.

What’s your current favorite tool or material to work with?

I’m really into long hair cowhide as a material, I have it dyed in outrageous colors. The Miller TIG welder is essential though, I use it pretty much everyday and consider it as a tool for drawing in three dimensions.

What book is on your nightstand?

Day of the Triffids by John Wyndham, it’s a classic!

Why is authenticity in design important?

Everyone is inspired by something, we all influence each other, particularly now that we are so interconnected. I think that the most important thing is to make sure your intent is genuine and that you can be honest about your inspirations, I borrow from nature all of the time.

Favorite restaurant in your city?

I prefer eating outdoors, any excuse for a picnic and the more elaborate the better. Now in Margate, we sometimes cook on coals with a portable BBQ oven on the beach after a swim at sunset, it’s so much fun!

What might we find on your desk right now?

Hundreds of colorful markers and pencils, 3 hard drives, a RAL swatch book, a postcard with a hovercraft on it and some fossils.

Who do you look up to and why?

Franz West, he was both brilliant and totally bonkers

What’s your favorite project that you’ve done and why?

Milk, the cafe that I built with menswear designer Kit Neale for the British Fashion Council. We had so much fun, he is an outrageous flirt and really up for a laugh. We even had a road trip through Northern France and Belgium to collect materials too in my old blue van.

What might we find on your desk right now?

Hundreds of colorful markers and pencils, 3 hard drives, a RAL swatch book, a postcard with a hovercraft on it and some fossils.

Who do you look up to and why?

Franz West, he was both brilliant and totally bonkers

What’s your favorite project that you’ve done and why?

Milk, the cafe that I built with menswear designer Kit Neale for the British Fashion Council. We had so much fun, he is an outrageous flirt and really up for a laugh. We even had a road trip through Northern France and Belgium to collect materials too in my old blue van.

TRANSCRIPT

Jonathan Trayte: I love exploring, both in the natural world and in the studio, those two things go side by side.

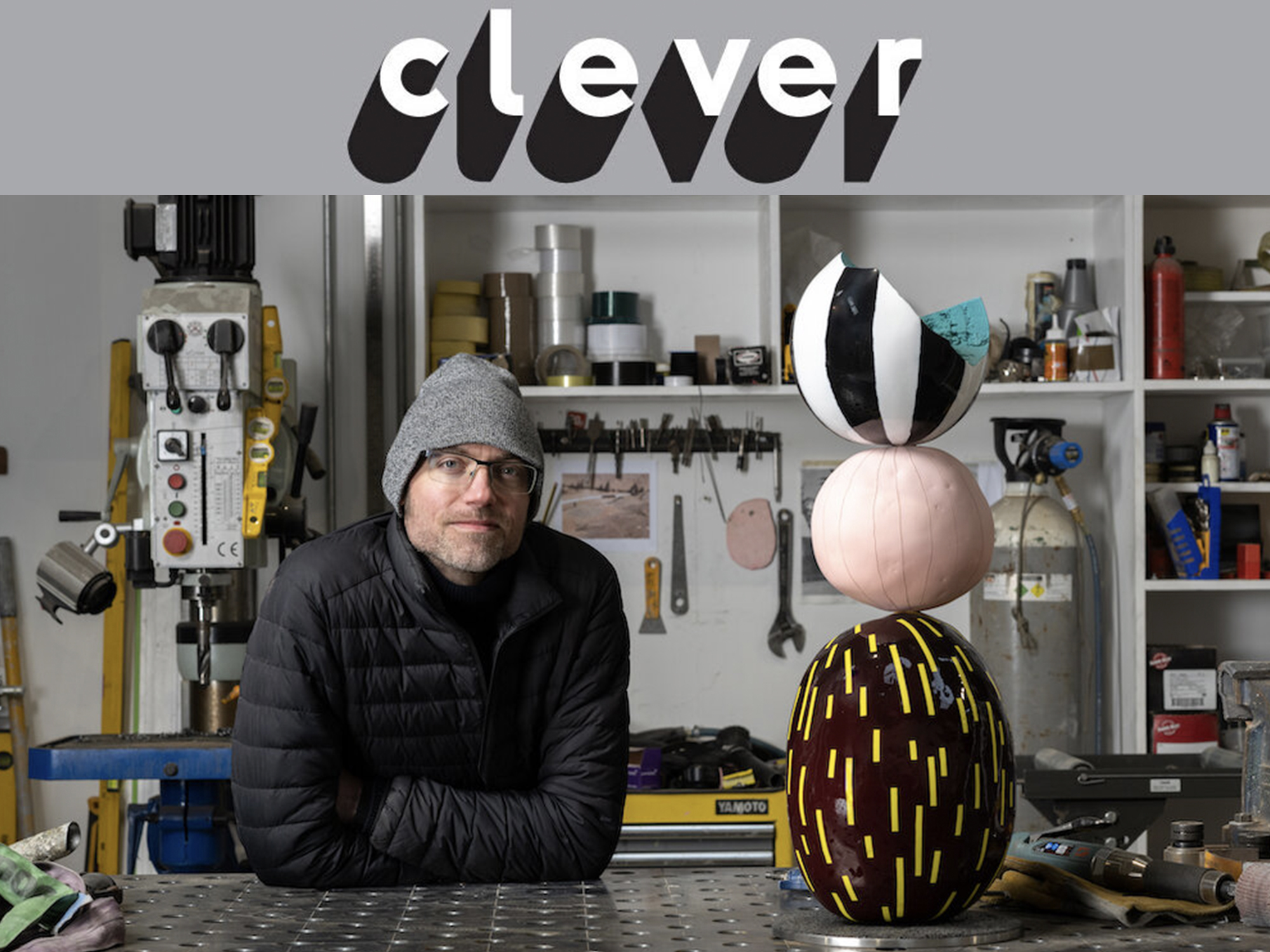

Amy Devers: Hi everyone, I’m Amy Devers and this is Clever. Today I’m talking to artist Jonathan Trayte. Jonathan Trayte’s work lives at the intersection of sculpture and furniture. It seeks to reinterpret modern consumer behavior and explores the psychology of desire through surface, material, light and color. His approach to making involves using a wide range of materials, methods, and processes. Drawing inspiration from both manmade ephemera and the natural world, he conjures surreal manifestations and seductive combinations. The work is a coming together of natural forms and saccharine colors, glossy synthetic skins of paint, resin, or glass, give the work a colorful pop status, a chameleon appearance and an almost edible quality. He recently wrapped a solo show at Friedman Benda titled Melon Melon Tangerine based in the UK in Margate, Kent, to be specific. He holds a Masters of Fine Arts from Royal Academy School and has been included in numerous international exhibitions. Here’s Jonathan.

JT: My name is Jonathan Trayte, I’m a sculptor, visual artist and I’m working currently in Margate, in Kent, south of England. I’m a maker. I’m inspired to create artworks and design pieces for a living.

Amy Devers: So in order to understand who you are now, I always like to go way back to the beginning. So can you talk to me about your formative years, like where did you grow up, your hometown, your family, what kinds of things captured your imagination as a young Jonathan?

JT: Sure, I was born in Huddersfield in Yorkshire and it’s kind of semi-rural life. My father has always worked overseas and then when I was only a couple of months old my mum flew me to South Africa to meet my dad who was working out there and we lived in South Africa until I was about five years old. One of my sisters was born out there whilst we were living there. So the first five years of my life I was running around. We were in really rural northern South Africa, near the Kruger National Park, only maybe a stone’s throw from the perimeter fence.

It was pretty basic living. It was dusty, essentially like a trailer park for a huge construction project that my dad was working on, so it was very unglamorous. But what it meant was that we had access to the most phenomenal landscapes and they had like a VW camper van that had like a pop-top and that took that all around South Africa on his days off, or the weekends, or whatever.

That was the first five years of my life. But I was born in Yorkshire and we returned there later on the rest of my childhood was spent in the shadow of the Pennines. The Pennines are a small mountain range that run like a spine through the north of England up into Scotland. They’re not huge, they’re nothing spectacular, but I have to say hills are a part of my life. And now living in the south of England, I sorely miss them. It’s something that I lament.

AD: So the first five years with the landscapes and the camper van and one sister, how many sisters and siblings –

JT: Two sisters now and one brother..

AD: And you’re the oldest?

JT: I am the eldest, yeah.

AD: I mean that does sort of free and fun doing the van life as a five year old –

JT: Yeah.

AD: [Laughs] What were the elementary school years in Yorkshire like?

JT: They were comprehensive, finishing in a comprehensive high school, but middle school, music lessons, pretty standard stuff. I did okay in my exams. I did well through school-ish, and didn’t get into too much trouble.

AD: Was creativity something that started early on and was supported or did you kind of have to fight for it or find it?

JT: No, I don’t really remember my time in South Africa, but I have a very clear vision of what it felt and looked like through my mum’s photography. She was just an amateur photographer but she captured some amazing shots, all of which was on slide film. In my early childhood we used to drag this huge, ungainly slide projector out every few months, or once a year or whatever and we’d just go through, take a whole weekend, we’d just go through slides and make pots of tea and just remind ourselves of what it was like being there.

That was a very creative aspect to my very early childhood. And my mum has always been really supportive. My dad was always working overseas and he still works, he’s working in Nigeria at the moment. The other thing is that where I grew up was very close to Yorkshire Sculpture Park, which you may not know of. But it’s quite an important landmark in the UK in that it’s where a lot of Henry Moore sculptures were placed.

Early on he was a big deal in the UK and seeing those as a child, seeing the Barbara Hepworth’s as well, and later on, became more inclusive, there were a lot more artists, a lot more sculptures there. Seeing Carrowss or whatever, that’s where we went for walks at the weekend or for picnics. And it was seeing those sculptures as a child, as a younger child, that made me feel like art was what I wanted to do.

I don’t think I ever really had a clear thought, it was never that I had, like an epiphany or a moment of clarity, it just became part of who I am, I think.

AD: Well that would make sense and I think that as a young child seeing how those sculptures sort of take up residence in the public, not only the landscape but the public consciousness allows for a mental pathway to form, to kind of understand what a sculptor does and how it might influence the world around you.

JT: Absolutely, yeah. And how it manifests too, you know, what sculpture means.

AD: So, how did the adolescent years play out for you and were you finding your creativity or were you in any way sort of needing to express some angst or anxiety?

JT: No, I’ve always been very creative and even when it came to my bedroom, I got rid of my bed and I slept on the floor at the age of 13. I always challenged conventions. I mean creativity went across all kinds of different avenues in my life. And I had a passion for cooking. I made some hideous meals, but I was excited to experiment and my mum was really encouraging in that. She was happy for me to just mess around in the kitchen and try things out.

JT: I think also the time in South Africa, traveling around, seeing the landscape, that being primarily the most sculptural aspect of the experience, but also there’s a lot of roadside attractions for tourists, sellers exhibiting their soapstone carved busts or chess sets, all of that kind of thing. I think that all has an effect on how you see materials in the world and how you think about creativity.

AD: Absolutely. It seems like it was a sort of, not really a question that you were going to study sculpture in university.

JT: It was accidental –

JT: I’d dropped out of A-Levels, I was still in higher education, or further education, I’d gone to the sixth form to study A-Levels and hated it. It was just a continuation of school; it was just mundane, just grim. And the one thing I had a passion for was art. So I went and did a B-tech, which was kind of a step sideways from A-Levels. It was considered lesser, but it meant that I could spend the whole time in the dark room doing photography.

I didn’t have to divide my time between other subjects that I had less interest in. It so happened that the two teachers that I had the most connection with, on this B-tech were textile tutors. And they were so influential and positive and encouraging that I actually considered pursuing textiles or textile design. There was a course, kind of a sculptural textiles approach, there was a course in Manchester that I thought I was going to go to.

And it just happened that a friend of mine who was studying down in Kent invited me to come and visit and I saw the course and I realized that actually I was on a wrong path and that sculpture was what I really wanted to pursue.

AD: So that B-tech was very, very impactful in terms of allowing you to focus it sounds like –

JT: Yeah.

AD: So you decided to study sculpture after thinking you might go onto textiles, and then when you went to do sculpture, did you go straight from your BFA to your MFA or talk to me about your years of creative study?

JT: Yeah, well, so all the while I thought I wanted to study textile art, I’d pursued photography and photography was my main passion. But I just had no desire to become a photographer or to work in the photography industry. So I was feeling a bit lost and then I found sculpture. But on the BA we studied on, I had a lot of fun and we learned quite a bit. Most of it was self-led, so you had to enable yourself in whatever discipline you thought you might want to focus on.

But I think it was at that point in the UK that university courses were kind of falling apart. Sadly, I think the education system is in a bad place and our course wasn’t great. And I needed to subsidize my income, I don’t come from a wealthy family and I had to pay my way through university. And so I took a job in a kitchen, in a farmer’s market, it was kind of a one-of-a-kind, it’s called The Good Shed in Canterbury and they have a huge, it’s like a huge, old railway hangar with a farmer’s market and kitchen attached and they used produce from the market to supply the kitchens.

AD: Oh, that sounds great.

JT: It was amazing and what I learned about food informed everything that I now know about sculpture.

Working with the team there, working with hot materials, hazardous environments, it’s all informed how I think about making art. So actually that was the most rewarding part about studying in Canterbury, was the paid job I did in the evenings with a team of chefs.

AD: Wow, can you illustrate that a little bit for us?

JT: Well, the chef, Raf, he is a Spaniard and so he trained in the Basque regions. The Spanish have an approach to food that’s really kind of, it’s minimal and it’s visceral, it’s just really present with the ingredients you’re working with. There’s not a lot of fancy technique, it’s more about creating, like maximizing your flavors with what you’ve got.

But he was really happy to experiment and encouraged us to experiment and the menu changed daily. We never repeated the same thing. And it was just a huge learning curve about materials. From sugar to glass, from flour to plaster, all of these things are interconnected. And it just taught me so much about materials.

AD: I love that and I can see it. It’s starting to all make sense to me. So what happened between getting your BFA in Canterbury and moving on to your MFA at the Royal Academy?

JT: Having worked in the kitchens, I’d learned a lot and again, this passion for things that are appetizing and repulsive, things, handling of materials, but I hadn’t really learned a lot about making sculpture. So I then set about acquiring the skills in order to pursue a career as an artist. I worked for other artists like Gary Hume, for example, I worked with Kim Meridew, who is his close friend and he’s a stonemason, so he taught me everything I know about stone.

I worked metal fabrication, I ended up working in a foundry and so over the space of maybe four years I focused primarily on acquiring skills. And it’s then that I applied to go to the Royal Academy of Arts in London, not thinking I’d get in. And amazingly did. The lad from Yorkshire who has spent most of his time in a kitchen got into the Royal Academy, so it was really exciting, also a bit kind of, a bit daunting.

AD: Yes [laughter]. So, you packed up and moved to London and how were your Royal Academy years?

JT: Amazing, like a family. There’s only maybe 16 or 18 students per year group, so a really small course and that’s across all disciplines, painting, photography, sculpture. And it’s a three year course too. So you really get to know everyone that you study with quite closely. And you know, it can be a bit abrasive sometimes. Someone plays music too loud and it’s just like having a sister that’s just annoying you. But it was really, really rewarding, it was a fantastic time.

AD: What was the transition like from student to professional?

JT: So I’d spent the years at the Royal Academy working in a bronze foundry, simultaneously.

JT: This gave me enough income to support myself, but it also gave me access to the workshops for my final show I cast a series of bronze sculptures which was really kind of the foundry owners. They kind of sponsored me, they allowed me to use the workshops and I just paid for the raw materials and I just put the time in. But what this meant was that I had a series of glossy, appealing bronze sculptures on show in my final exhibition that all got snapped up, everybody wanted a piece. So it was kind of a plunge into a professional career. I had clients wanting artworks, I had to get my studio set up properly and it was a baptism of fire really, it was intense. But it was exciting.

I had quite a few exhibitions, people obviously had seen the show at the RA and they wanted me to produce work of a similar vein for further exhibitions. They’d seen the response it had got to, so it meant that a lot of people, there was kind of an appetite for these bronze sculptures. But there was no room for experimentation. So whilst I had quite a few interesting exhibitions, I quickly lost interest in it and I became a bit jaded because it’s just, I just got a little bit lost.

And as a sculptor I was not solely focused on casting melons in bronze. So I was desperate to experiment more. And I went through a little bit of a time where I’d said no to some things and I had a bit of a rocky patch where I just felt really, yeah, lost I guess. And then I had another exhibition at, it was for the [Converse Dazed?] where I built an installation with everything that I had been experimenting with. There were bronze sculptures in there, but there were wallpapers, concrete marrows, live plants, printed textiles, I mean glazed ceramics, everything, I just threw everything at this exhibition. And it was a real, it was just really exciting. I felt alive, you know, it was exhilarating.

AD: So it can be a strange thing when you make a name for yourself, you make a splash or an impact with your bronze sculptures and then of course everybody wants that and that’s sort of what drives your income until you almost have to break out of that cycle or the cycle will consume you. And when you did this exhibition with everything that you’ve been experimenting, do you feel like it established for the world that you were not gonna be the bronze sculpture guy and that they would now have to accept you as this person who works with all these different materials? [Laughs]

JT: I think for a lot of my peers, they were really impressed. I got a lot of compliments on the show, but it wasn’t really that well publicized. I don’t think, it didn’t really define who I am, but it was more important for me as a person, as an artist. It gave me the confidence to really pursue these other avenues that I’m interested in. And it led on to a museum show at The Tetley in Leeds and for that show I really threw everything at it too.

And I brought back all of the bronze sculptures, but they’d shifted slightly. And also the gallery space at The Tetley is an old office building for the brewery –

It’s a beautiful space, but it’s got oak panelling and parquet floors, it’s quite dark. And so I took the decision to illuminate some of the bronze sculptures, just to give punctuation to the space. And that was the beginning of the lamps and it was a real step forward for me. It just changed the way I thought about things entirely. So yeah, I think that show is the one that really changed things.

AD: Changed things for you or changed things for how you were perceived in the art space?

JT: Both, yeah.

AD: How were you able to sustain yourself while you’re doing this experimental phase?

JT: Well, I’ve always been quite lucky in that there have been collectors keen to support me Sales have been thin at times, but I’ve always managed to kind of eke through and also, I mean up until about four years ago I was still working part time at the foundry that I’ve worked at in London and supported myself when times are lean, doing paid work there. And they were always happy to have me. They’ve been so supportive. But they’ve also taught me so much. The only reason I know how to do any metal work at all is because of the time I spent there.

AD: It sounds like a wonderful relationship.

JT: Yeah, it’s really good. I think it’s quite rare now as well because employers have to protect themselves from flaky staff. You can’t have someone that wants to do a month’s work and then nothing for two months because they’ve got a show in Barcelona or whatever, you know? So I was really lucky.

When I kinda had that down time and I was questioning everything, I was trying to work out what kind of an artist I wanted to be and how it was going to fit in the world. I took the decision to say yes to everything, and that’s what I’ve done since. And it meant that some opportunities that came up, that might on paper have seemed a bit lackluster or not really worth the time, I would commit to, but I would then do my best to make it something that was positive, that was going to teach me something or introduce me to another person that’s influential.

So I’ve done lots of different projects, but one of those things was a collaboration with the British Fashion Council and we were asked to produce an artwork and I was put with another fashion, called Kit Neale who works in menswear and we were given £5,000 to make an artwork that they were then going to auction, sell to a client and fund the next year’s collaboration. It seemed okay, 5,000, it was a nice sum of money, you can do something with it but you can’t do a lot.

And we just didn’t really want to produce a static artwork that gets whisked off and hidden away. We wanted to create an experience and Kit has a lot of experience in the fashion industry running campaigns. He’s collaborated with a lot of commercial businesses, Lavaza being one, something I’ve never done. So he negotiates with them and we persuaded Christy’s, who were sponsoring the venue, to allow us to close their café and open a new one in the galleries. And we set about using my material knowledge and both of our really hard work to build a café for people to use for two weeks.

And that was the first time I made seating and tables. And it was just really, it was just a huge challenge, but it was worth every minute. And it was just, it was a great experience.

AD: I just got goosebumps. Because I can kind of feel things coalescing for you in terms of your sculptural work, your material knowledge, this collaborative relationship, but also venturing into you know, functioning sculpture as a way of encouraging interaction and influencing the experience as opposed to just the view.

How did you feel about that? Being responsible for an entire environment as opposed to a static piece?

JT: Because it was a collaboration and also it was sideline to my main practice, it wasn’t an exhibition with only my name at the top. I felt free to experiment without any real risk of comeback. Obviously I wanted to do my best and put my name to it, but I just didn’t really have the same pressure that I would usually put myself under. And what came out of it was much more creative and positive than I’d ever imagined. And that immediately fed back into my work.

So this kind of happened just, I think maybe a month after the show at Leeds, at The Tetley. So these two experiences, making the lamps and then making the tables, all in the same quarter of the year, then focused all of my drive to pursuing making a series of lamps. And then I did a show at Christy’s again, six months later, in collaboration with Anton Alvarez and Andreas Siegfried and I showed 12 lamp sculptures with neon and all sorts going on. So that, again, was a really important show.

AD: I’m also wondering if that freedom you had while working on the café with Kit Neale, is that freedom something you were able to afford yourself moving forward?

JT: Yeah, bizarrely, so I’ve come to making like furniture like artworks from an artist’s perspective. It might seem odd to some people, but in thinking of function, that actually gives me more freedom. There’s less pressure. A static, sculptural object is so loaded, you know, the place I was telling you about, the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, when you see the Barbara Hepworth, Family of Man, or you see one of the Henry Moore’s up on the hill, it’s so loaded and heavy and yeah, static, that’s the word. You’re not allowed to touch it, you’re not allowed to sit on it.

And we always did, when I was a kid there were never signs saying, ‘Don’t climb on the sculpture,’ we used to use them as slides and I told Helen Pheby, the curator there that we know now and she was horrified. She said, “Yeah, don’t do that!” [Laughter] But yeah, so for me venturing into functionality gives me immense freedom, it’s exciting. And also working with Friedman Benda, which I’m sure we’ll go on to talk about, they are just amazing. I mean what a great team, what a great gallery.

AD: Yeah, so that’s what I wanted to ask about next. You just completed a solo exhibition at Friedman Benda entitled MelonMelonTangerine, so I want to hear all about how the show came together and how the work that you made for the show came together?

JT: We had a plan to exhibit work now despite what’s been going on around the world. And it’s something that I’ve been working towards for a year. I had to move studios and set up down here in Kent because I needed a much bigger space, much larger than anything you can get in London. So that was a big shift for me. But the year before I did a road trip, I met my wife in LA and we drove to Nebraska. And we took like a 2,000 mile detour around through southern California, Arizona, Utah –

AD: I have to back up. You met your wife in LA, meaning you met her, you met her?

JT: No, sorry –

AD: You already knew her and you met up in LA?

JT: She was already my wife, yeah [laughter], so yeah, we met actually at the Royal Academy. She’s from Long Island originally –

JT: Yeah, she came to study at the RA in our year group and yeah, we hit it off while studying and eventually we got married. She needed a visa which is like, oh god, we’re gonna have to get married now. [Laughter] And now it just seems like you know, obviously it was the right thing to do, so.

AD: Okay, so I’m back to your road trip now.

JT: We drove to Nebraska, through this southern, you know, Southern California, Arizona, Utah. And got to see some of the things that I’ve been dreaming about. I’m obsessed with that landscape, Paris, Texas is one of my favorite films and those arid desertscapes, they’re just etched in my mind. So you know, visiting Joshua Tree, I know it’s not Texas, but it was just mind blowing. And that’s what fueled the content for this show.

And viewers might feel like it’s kind of a disparate connection and they might look at the work in the show and say, oh, how does this fit with the west. But it’s there in spirit, it’s there in the materials, or it’s there in the vision of some brazen plant that’s defying all natural laws and thriving in this arid place. So, that’s what fueled the work.

AD: I can see that. I also, I’m curious about this road trip because it seems to me a little bit like van life, South Africa, two point oh.

JT: Yeah. I’ve never really made that connection, but yeah, you’re right, I guess it is.

AD: Did you take a lot of photos?

JT: Many, many photos, yeah, and we just chucked a tent in the back, we did day hikes, we slept rough in the dirt, we climbed into the Rockies and pitched a tarp. In fact we didn’t have a tent, we just had a tarp, slept on the floor with a canopy in case it rained, which it never did. And just slept wild for two and a half weeks whilst driving huge swathes of the country. It was amazing. I would do it continuously if I could. I wanted to just carry on north all the way up to Canada, but the time didn’t allow for that, so.

AD: That does sound wonderful and free and wild, and I can see both the landscape and the sort of makeshift structures in your work.

JT: Yeah.

AD: I am wondering if you met your wife at Royal Academy, then she’s an artist as well?

JT: She is, she’s a sculptor, yeah. Her name is Rachael Champion, she’s more of an installation artist, but she’s done big outdoor projects and she’s an inspiration.

AD: So, can you talk to me about your creative process? We sort of understand where the genesis of this work for the Friedman Benda show came from in terms of your road trip, but how does that sort of imprint on your brain and then germinate into an idea that will then have materials associated with it? Can you walk us through that?

JT: Well, all the while we’re driving or hiking in the mountains or whatever, I’m having ideas about how some inspirations I’ve seen, mind blowing lichen or a tree that’s missing two branches, whatever it might be, how that might influence an artwork. That coalesces when I come to sit down and draw concepts or draw ideas about artworks or pieces of furniture or whatever it might be that I’m working on.

And I do a lot of drawing, it’s really handy for, both for me to visualize how something might come together, but also for the team at the gallery about what it is that I might be planning or what a show might look like. There’s a huge collection of these drawings, as I’d tried to articulate this language, this visual scene that we’d been through. And that led onto, a choice of materials and processes and ultimately some sculptures that came out of it.

AD: You work in such a wide range of materials. Can you tell me and our listeners about what some of those materials are, what it is about the materiality of those that appeal to you and how they’re meant to communicate certain aspects of what it is you’re attempting to communicate?

JT: Having worked in the kitchen, I’ve always been used to trying to incorporate a wide variety of flavors or textures into a meal. Something that’s sweet yet has got a salty aftertaste, or something that’s velvety but it’s got something hard and crunchy. And this all relates to sculpture and how I think about making artworks. And for me it’s really important to combine as many materials as I can and I know that there are designers and artists out there that go way further.

For me it’s about creating a language and aesthetic that’s both pleasing and also slightly nauseating. Because I feel like nothing is ever perfect in life and these sculptures are obviously, they’re referencing life itself. For me it’s important that there’s some conflict in the work, you know?

AD: What is nauseating for you in life? I mean I’m not asking as though that’s a weird concept, I’m saying yeah, no, that’s obvious, but can you put, make it real for us?

JT: Sure, like beautiful sunny day, but the seaweed has come up on the beach and so whilst you’re seeing this beautiful sunshine vista, you’re also smelling this slightly sulfurous smell. Or you’re driving through the countryside and you’re heading down to the cliffs for a day hike or whatever, and you accidentally clip a sparrow that flies out of the bush into the front of your car.

AD: I got you, that was helpful though, thank you for giving me some examples. Because that helps me also draw the connection to your work because I think one of the things that’s so provocative about it or so, actually really appealing, even though you have that sort of language of something that’s pleasing with a touch of nausea [laughs], that’s what makes it really appealing to me because it’s not saccharine and it doesn’t take for granted a certain predisposition of the viewer. It also doesn’t seem to be espousing any sort of judgment on the nauseating part of it as much as it is sort of holding those two conflicting things together in a weird form of harmony –

JT: Nice, yeah, I like that. Because it’s all part of life – nothing is crunchy if you haven’t got soft things [laughter].

AD: True.

JT: Yeah, so everything is as important as the other.

AD: So, just from a purely practical day-to-day perspective, if I were a fly on the wall in your studio, what does it look like and what would I see on an average day because you work with so many different materials, I need you to take me there.

JT: I primarily work on my own and I had a great assistant during the preparation for this show at Friedman Benda, but because of Covid, we’ve had a lockdown here and it’s just been impossible to get help on a regular basis. And also, I quite like working on my own anyway. At the moment I’m working on a set of dining chairs, so it’s currently a metal workshop. But also I’m working with some beautiful American black walnut and each chair has an aspect of walnut.

So I’ve got two stations set up at the moment and both are creating a huge amount of dust and mess as I plough through all of this fabrication. But also it’s very industrial, but there’s also a lot of plant life. I get a lot of inspiration from the natural world and the few bizarre specimens I have growing, I’ve imprisoned in my studio, the poor things, they get covered in dust and I have to hose them down. But they give me a lot and there’s a lot of succulents and cacti and palm trees in my studio.

I also adorn the walls in particular areas with a lot of inspirational material. It could be anything from, I screenshot things from Instagram sometimes because I’m so poorly educated when it comes to design, the history of design. Glenn Adamsom was laughing, saying about, most designers talk about influencers from the Bauhaus, but I’m more interested in crisp packets or biscuit wrappers from Sainsbury’s. Yeah, I mean all of these things are an influence and I have books scattered about.

I’ve recently been combing through Babardi book and Franz West, who has sadly recently passed. He’s always been a huge inspiration; I hope to glean some of his insight in my work. And I have a forklift, I always play music, I love traveling around the world listening to different music. I usually listen to Ravi Shankar in the morning. I’m on a farm, there’s a lot of birds on the farm.

AD: Do you have like a big barn door you can swing open and be –

JT: Yeah, I’ve got a huge, four/four and a half meter roller shutter, so as soon as I get in, rain or shine, that goes up and I am kind of outside.

JT: And it’s freezing cold sometimes and then others, it’s south facing, so we get the sun, it’s really nice. Rachael has her studio next door now and she’s also sharing with two other artists who are based in Kent. Louise Beer and John Hooper, John is a photographer. He’s actually, he’s been photographing my work and he’s a photographer, an artist in his own right. And Louise too is an artist and they’re interested in astronomy, so we have a telescope at the studio and we all have lunch together, it’s a really nice environment. It’s such a stark contrast to London which my studio was above the foundry. This is why I had access to that employment all those years. I had a live/work space in the top floor of the foundry. So everything I made prior to leaving London came down six flights of stairs in an industrial building stairway.

AD: So, I’m really glad you painted that picture of your studio for me, and you really did take us there and it does seem like you’ve built for yourself a nice place to kind of spread out and give yourself the freedom to make a work that you want to work. Would you say you’re in a good space to do that?

JT: Definitely. The only thing lacking is the topography, the terrain that I long for, from my childhood. I miss the hills. I would love to move north one day or move further afield. I mean we talk about going to the Canaries, just because of the volcanic sand, but I’ve never actually been there, it just looks nice in photos.

AD: When the world opens back up, I’m sure you’ll have those opportunities and you can explore the world and scout it out for new domiciles.

JT: Yeah.

AD: [Laughs] In thinking existentially about you as a human and your contributions to society and what this is all adding up to in terms of why you’re here [laughs], what would you say is the main motivation that guides your drive and purpose?

JT: It is a pertinent person in question for these times. I think a lot of people are taking a step back and questioning their motivations and their aspirations. I think it’s interesting that more and more people have pets now and I don’t know what it means, but it certainly means something. I think people are suddenly realizing that they’ve been all-consumed for so long and actually taking a breath and a step back from the ferociousness of modern life, is a good thing.

I honestly, I don’t have a succinct answer for you. I don’t really know. I’m still learning and I’m still figuring things out. I’m 40 and yeah, maybe I’ll never find the answer. I guess I get a lot of satisfaction in exploring through materials and I’ve heard it said that everything you make is a self-portrait and it’s funny, because I normally just wear a black wool jumper and a beanie or hat or walking boots, that’s me. So when you see the Kula Sour daybed, you do wonder how I came up with such an odd looking thing. But [laughter] yeah, I just, I love exploring both in the natural world and in the studio, those two things go side-by-side.

AD: I agree and I can see that coming through your work and one thing we haven’t really talked about yet is you’ve said this in reference to your work, that it’s informed by our global appetite for consumption. And the manipulation that advertising does on us to influence our decision making. And I wonder if you, since that’s something that you’ve been attuned to, and you’ve had your finger on the pulse of, I wonder if you can feel that changing at all in these times?

JT: I can feel it changing a little, it is interesting to hear other people’s perspectives, both about what’s been going on or what we have or haven’t done right. But I’m sad to say that I feel like in a years’ time people would have kind of forgotten and they’ll go back to whatever it was they were doing before. I really hope that this is a moment to really question our motivation as a species and to think more about the natural world and how we need to change from a continual growth to more of an intelligent way of being.

I need to go back. My shot at the RA, another reason why I felt so jaded about continuing to make those bronze sculptures. They were really fun to make and I gave them ridiculous titles. Like The Beautiful Dutch Woman… and they were just stacks of painted bronze casts. But what informed that decision to make that body of work was the fact that cycling into central London, the Royal Academy is bang in the middle of Mayfair, just of Piccadilly.

And so I would pass Prada and Gucci every single day in my tattered jeans and my work boots, coming from the foundry, going into the studios. And I’d be passing all of these buildings and all these fancy cars parked up and people bustling around with these silly bags. And that body of work was a criticism on the way, you know, we have this desire to surround ourselves with baubles. They were baubles, essentially.

Yeah, that kind of criticism has always been in my work in some way or other. It’s less so now, but those bronze sculptures, they are baubles. I think of them as kind of garish symbols of our desire to consume.

AD: And where do you feel the Jonathan Trayte story going from here? I mean other than migrating to the Canary Islands?

JT: [Laughter] I have an insatiable appetite to travel and our plan is to travel a lot more when we can, but travel in a more sensible kind of way. I’ve never really done a lot of long haul flights, but there’s places in Scotland I’ve never been. I’ve never been further north than Edinburgh. So I want to go and explore the British Isles. Work-wise, I have, purely by accident, ended up working with an amazing gallery who are really supportive and really encouraging and continuously challenging me to produce artworks.

To challenge myself and to experiment. There’s kind of a safety in having their confidence which allows me to experiment. I just hope that this continues to bigger and more ambitious projects. Some of the artworks in the show were intentionally designed to go outside. They were small enough to fit in a gallery, but making outdoor installations is kind of a Catch-22 because you need to have had the experience and the material knowledge to be able to do it before you get given the opportunity.

So my approach has been just to make them. If I need to prove myself, I’ll make some then. And I’m hoping that that leads onto some really ambitious outdoor artworks. But that’s not to say I don’t enjoy doing gallery exhibitions and making smaller pieces too. So yeah, I don’t want to say, to decide on what’s going to happen in the future. I’m just really excited to see what comes and to just throw everything I can at it and experiment and challenge myself, you know, learn things on the way.

AD: I love it. Well, I am excited to see how the story unfolds. Thank you so much for sharing everything and for painting those glorious really illustrative pictures of your studio and your work and what goes on in your brain and the road trip. I was right there with you.

JT: Thank you for having me, it’s great to be here. I’m flattered you asked.

AD: Thanks for listening! To see images of Jonathan’s work and read the show notes, click the link in the details of this episode on your podcast app, or go to Cleverpodcast.com where you can also sign up for our newsletter. If you haven’t already, please subscribe to Clever on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. And if you would please do us a favor and rate and review, it really does help people find us. We also love chatting with you on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, you can find us at Clever Podcast and you can find me at Amy Devers. Clever is produced by 2VDE Media with editing by Rich Stroffolino, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan and music by El Ten Eleven. Clever is proudly distributed by Design Milk.