By Arthur Lubow

A gold-finished, bronze tabletop rests on a crinkled pedestal that emerges from a glazed blue boulder. A light fixture ringed by pink shearling hangs in the air like a flying saucer. A couch is composed like a jigsaw puzzle of interlocking, brightly colored biomorphic shapes. With each one of-a-kind piece he designs, Misha Kahn, 33, gives physical form to the universe that exists in his mind.

“I’m trying to build this whole parallel world through these objects,” he says. “We’re so used to imagery that reflects a skewed vision of our world, but we’re not used to seeing objects that do that. A functional object quickly allows you to imagine other things that exist in that vein. You can extrapolate a whole scene from there, with architecture and vehicles.”

To understand Kahn’s métier, it’s important to know that he stumbled into it. After transferring to the Rhode Island School of Design from a small art college in his native Minnesota, he entered the school’s furniture design program, one of the few majors that allowed transfers. It was at RISD that Kahn discovered his love for designing things that could, at least in theory, be used. “It was really hands-on,” he remembers of his object training, “and very friendly toward making idiosyncratic one off things.”

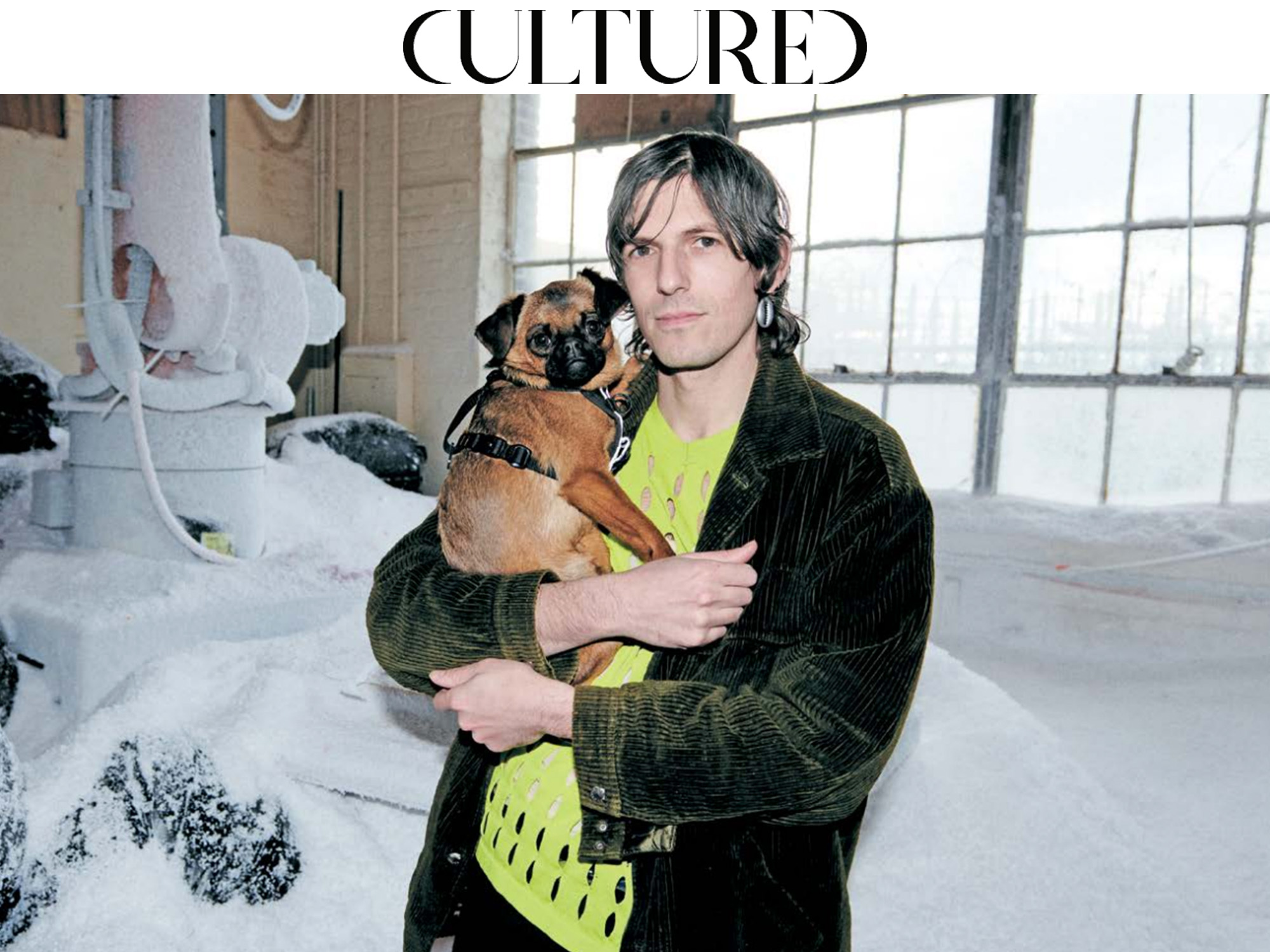

A boyish-looking Brooklynite who lives in Greenpoint and works, flanked by six assistants, in a studio in Sunset Park, Kahn dresses colorfully enough to compete with his furniture. In 2021, he joined forces with the fashion designer Dries Van Noten, who gave the artist a show at his Los Angeles store and collaborated with him on a splashy silk bomber jacket and a T-shirt, adorned with shapes suggestive of internal organs and color-stained like a Helen Frankenthaler canvas. The following summer, he staged his most comprehensive exhibition to date at the Villa Stuck, an Art Nouveau house museum in Munich, Germany, where his dreamy oblong pieces cheerily held their own within boldly patterned and marble-laden rooms. As part of the show, the museum furnished Kahn with a robot that the designer programmed to make paintings in the garden. It is now one of two in his studio—the second robot does three-dimensional carving. Utilizing advanced technology to put a twist on traditional forms and practices excites Kahn; he plans to use the Munich robot to produce an enormous painting for an upcoming corporate commission in New York’s Hudson Yards.

Kahn, who is mounting his fifth exhibition with Friedman Benda in nine years this month in Los Angeles, approaches the labor-intensive craft of furniture design with the spontaneity of a sketch artist, adopting improvisatory techniques and delighting in the aesthetic paradoxes that emerge as a result. Early in his career, he made a mirror frame by sewing together bags that he filled with yellow vinyl resin. “I was looking for loopholes,” the artist explains. “You see the stitches and the wrinkles from the bag, but you get a liquidy, smooth polish from the vinyl.” Seeking “super immediate solutions to casting,” he crumpled tin foil casserole trays and filled them with wax to create a mold for a one-off bronze work, the crinkly surface of which is about as far as you can get from the hyper-smooth hide of a Jeff Koons balloon dog.

When Kahn first discovered virtual reality software, he heralded it as a liberating means of improvisation. “You can fluidly draw things in V.R., manipulating this pretend clay,” he explains. After using the software to model his designs, Kahn would bring them to life, converting the 3-D files into fiberglass or metal sculptures. At first, the process felt as immediate as crushing tin foil, but eventually he realized he was losing more than he gained. “There was a satisfaction to seeing something so synthetic in the real world,” he says. “But now, V.R. is never the only tool that I use to make something. The first time you see it, it’s magic. Then you see it again, and it’s a party trick.”

These days, when Kahn uses V.R., he no longer renders the original forms it generates. Instead, he blends them with components that he crafts with his hands. Last year, Kahn made a large stainless steel table using digital design software before embellishing it the old-fashioned way. “Seeing the table combined with handmade glass pieces that fit into it is so pleasing to me,” he says. “There’s a tension from this very traditional craft meeting this hyper-digital object. It feels like the next step.”

Kahn’s designs are subversive and uncomfortable—physically and intellectually. His chairs don’t invite you to sink into them, and his tables are unlikely to support a dinner party. “On good days, I feel like I’m getting away with it,” he says. “On bad days, I feel there’s a design crowd that views me as making fringe, non-participatory objects.” Kahn takes comfort in his belief that the boundary between such categories as artist and designer is constantly eroding. “Ultimately, I think people want more and more fluidity,” he says. “The silos of culture take a lot of work to maintain. The next thing on the horizon is obvious. No one cares.”