By Julie Baumgardner

Photography by Oliver Matich

The British designer of fashion brand A-COLD-WALL* and founder of design consultancy SR_A walks us through the need for an artistic community, the influence of the severed diaspora, the power of beauty and the sacred elements of his design toolbox.

Can brutalism at once operate in the realm of craft and the human touch? Refrain from calling it a contradiction in the case of Samuel Ross, the multidisciplinary designer perhaps best known forhis “British working class-meets-Savile Row” fashion brand A-COLD-WALL* and his productive, creative friendships with Virgil Abloh.

Barely 30, this Brit, whose parents are Windrush-generation Caribbean, is already hitting benchmarks and garnering accolades comparable with designers far more senior. He’s won a British Fashion Award (2018), the Hublot Design Prize (2019) and a GQ Fashion Award (2020). Collaborations with Dr. Martens, Nike, Apple, Beats and Louis Vuitton are also under his belt. He regularly gives grant funds to emerging Black and POC designers, and he’s inside a creative circle of contemporary tastemakers who want to do things their way.

“If you think about all the great art movementsin history, they all came up through community, dialogue, discussion and the iteration of ideas. That’s something I believe in as a design process,” Ross says. Still, when it comes to fashion, he says, “It’s about contextualizing the idea and exploring that there’s a relationship with contemporary culture now, whilst ensuring there’s a signature aesthetic that’s easily recognizable.”

Ross isn’t satisfied with just working in fabric construction or image creation. He has a fine-artpractice and oversees a design consultancy he calls SR_A, short of Samuel Ross and Associates, founded in 2019. When it comes to design, I often see myself as a problem solver,” he says, “you’re trying to finda way to layer experience to be almost-discovered through engagement, haptics and touch.”

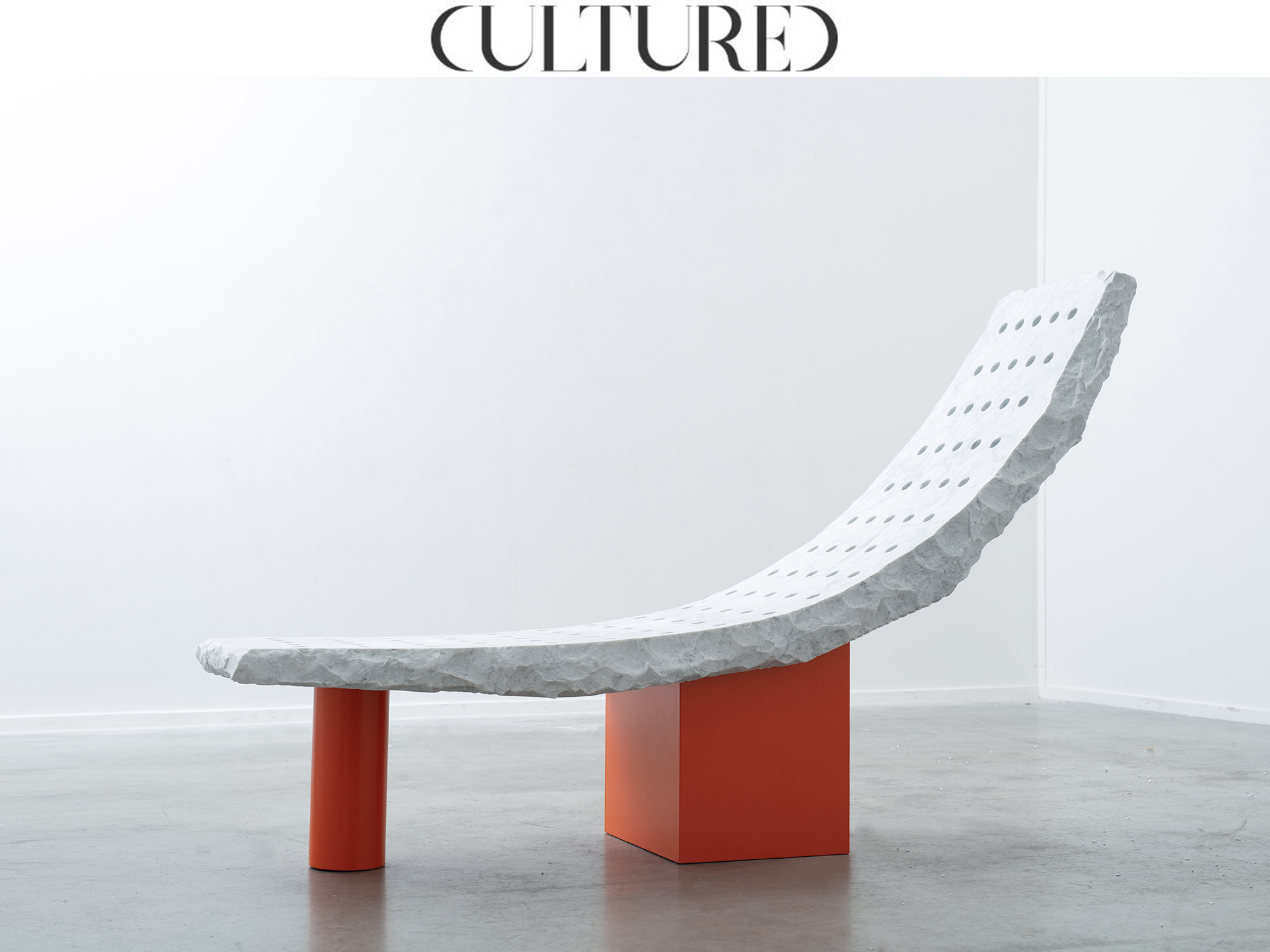

That all sounds a bit technical and philosophical—a point Ross laughs about—but looking at his latest series of work, “Rupture”—seating and tables that fuse hand-manipulated marble and machine-cut steel—there’s a palpable dialogue between cold, cool modernism (cubism, to be exact) and something much more human. That would be the West African references (e.g. Edo and Benin objects), Ross says, which “amplify the perspective of what it means to be part of a severed diaspora. You see the materials almostpulling away from one another.”

Ross has not been to Africa, but feels not only inspired by, but incredibly rooted in “Blackness living across digital services and spaces and finding ways to keep this interconnected voice and spirit.” He says, “It’s almost an obligation of being a minority to ensure the correct absolute documentation in what people of that demographic background were thinking in that time in history.” Still, “there’s an outrageousness” that a “British Caribbean guy is referencing this severance and dislocation,” he says. He wants to make clear that “What I’m trying to do is not necessarily talk always about trauma, pain, or fear or victimization or Critical Race Theory. I’m not. I’m trying to talk about the innate dynamics that exist from such a happening.”

His series called “Rupture,” and his well-publicized Trauma Chair, both of which will be at a solo-booth Design Miami/ presentation this December with his gallery Friedman Benda, are meant as totems of beauty. “There was a push to ensure that these works were beautiful,” says Ross, adding that in the studio the other day, surrounded by his team, “some of the works, they make you shed a tear. The ways the forms interact, you can feel the references. You don’t need to explain it.”

And likely no explanation is needed. As mightily as some have tried, disciplines can’t be contained within a singular identity, region or theory, particularly in a globalized, post-colonial, digitally driven world. Ross sees semiotics, semantics, color theory, proportions and geometry as “almost sacred laws” of design language. “I feel it’s a bit of a toolbox—you soon find out the cadences that have relationships and work together, and the ones that do not,” he explains, freeing him to select his references from any movement or moment. However that doesn’t leave his practice vulnerable to chaos or lacking cohesion. There’s a strict core to Samuel Ross, the firm and the man. “We are people of craft who care about material. We care about information being conveyed correctly in visual and haptic means,” he says. “It’s not luxury, it’s artisan.”

Ross’s roots, his family life and parents, helped carve him as a creative. “The craftsman, the artisan, the engineer, the maker: these traits were always encouraged,” he says. And though he occupies the haute world of art, design and fashion now, Ross is actively shifting centers of power and production, taking on canon and convention and fusing it withcraft and community.