His work, made of avocado skin waste, highlights how the trade is damaging Mexican landscapes and communities

By Francesca Perry

“It’s a story of hope, of how this big damage can be reversed,” says the designer Fernando Laposse. He’s talking about Cherán, a small town in the Mexican state of Michoacán surrounded by forested mountains. In 2011, as huge swaths of those forests were being destroyed by illegal logging — largely associated with rapidly expanding avocado production — a group of local indigenous people rose up to protect the land and fight back against the loggers, who were involved in a network of organised crime. These days, the town has an ambitious reforestation programme and a self-ruling indigenous government that has banned commercial avocado production.

From December 3 to April 7, Laposse’s new project inspired by Cherán, named “Conflict Avocados”, will be on display at the NGV Triennial in Melbourne, Australia.

The designer has made a name for himself through turning natural materials and agricultural waste — such as loofah, agave fibres and corn husks — into intriguing furniture.

For this project, he transformed waste avocado skins, collected from a guacamole stand near his studio in Mexico City, into marquetry for a cabinet. On the long, low, wooden credenza’s doors, the patchwork of avocado skins appears as a field of mottled browns.

“It requires a lot of labour,” says Laposse of the process, which involved carefully cutting and drying the skins before laminating them on to paper and stamp cutting them. The result is a curious yet surprisingly resilient material that “feels almost like leather”, he notes. It’s a process that builds on the designer’s “Totomoxtle” series (2018), in which he turned discarded corn husks into richly patterned furniture marquetry in hues of purple and yellow, a collaboration with a community of indigenous farmers growing corn in Santo Domingo Tonahuixtla, Mexico.

These aren’t your average waste upcycling projects. With “Conflict Avocados”, Laposse is not suggesting that designers start producing furniture made from avocado skins. For him, the work is a vehicle to tell the story of how the global increase in avocado consumption impacts real landscapes and communities in Mexico.

The country supplies most of the avocados consumed in the US, in response to skyrocketing demand over the past decade. Most production takes place in Michoacán — until last year it was the only Mexican region certified to sell avocados to the US — where significant deforestation and cartel violence linked to the avocado trade are taking a toll.

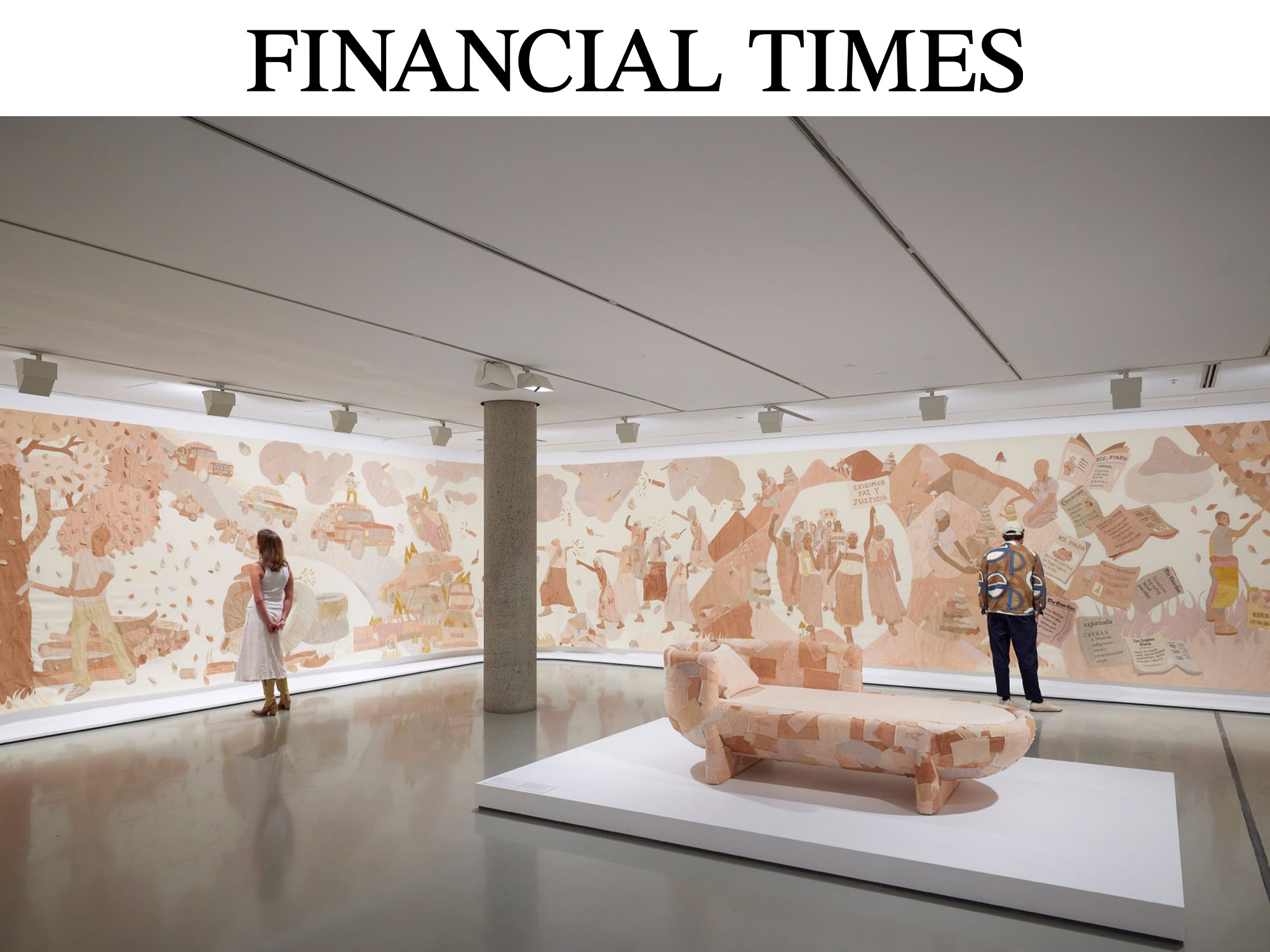

Alongside the cabinet, Laposse has crafted a 40m-long narrative tapestry — dyed using natural pigments from avocado pits and marigold flowers — that depicts the story of what happened in Cherán, as well as the wider picture of Mexico’s avocado industry. This is accompanied by a documentary film, focused on the people affected by the situation.

Before starting the project, Laposse had befriended an environmental activist working to protect an important monarch butterfly sanctuary near the town of Ocampo, Michoacán, from encroaching deforestation for avocado production. But in 2020 that activist, Homero Gómez González, was found dead, believed by many to have been murdered. Laposse’s film features Gómez González’s son, who is trying to protect the butterfly sanctuary in his father’s absence.

The designer created a gently curved yet monumental daybed as part of this project, “Resting Place”, in honour of Gómez González. The piece is upholstered using avocado-stained offcuts from the 40m-long tapestry, stitched with images of guns and chainsaws. What starts as a curious-looking collection of crafted objects becomes a sobering reminder of the reality behind our Instagram-friendly avocado toast — as well as the commercial forces driving it. “It’s engineered demand — no one was eating avocados 15 years ago,” Laposse says.

Laposse sees himself as an activist as well as a designer, noting that design can prompt productive collaborations and raise critical awareness. “The aim is to use these objects as objects of conversation . . . I focus on materials because it’s what sparks curiosity in the viewer,” he says. Ultimately, Laposse concludes, design is “another tool in the arsenal of things that can help you tell a story”.

“Conflict Avocados” is on show at the NGV Triennial in Melbourne until April 7 2024.