By Martha Pskowski

For Disegno’s 10th anniversary, we’re republishing 29 stories, one from each of the journal’s back issues, selected by our founder Joahnna Agerman Ross. From Disegno #22, Martha Pskowski charts the efforts of designer Fernando Laposse as he works with a community of farmers in rural Mexico as they attempt to revive the practice of growing colourful heritage corn.

The oxen are giving Heladio Ramírez a hard time. He deftly manoeuvres to tie the yoke over their horns, occasionally shouting in a guttural tone. “That’s how we communicate,” he laughs. Delfino Martínez Gil looks on as the sun rises over his most fertile plot of land in Santo Domingo Tonahuixtla, Puebla, a small town five hours outside Mexico City. Fernando Laposse, a London-based Mexican designer, confers with him.

Once Ramírez secures the yoke, he leads the oxen into the field to begin ploughing. This late January morning marks the first corn planting of the year. Today, they are sowing two varieties of native corn, interspersed with squash. The corn will be harvested in June. The cobs will be eaten or saved for seeds. The husks will be fashioned into lamps, wall installations and vases for Totomoxtle, a design project that Laposse began developing in 2015, and which has sold around the world. But today, the farmers are focused on getting the planting just right. Noé León García follows the plough, counting his paces to space out the seeds. His family has saved heirloom seeds for generations.

A few years ago, almost all the farmers in Tonahuixtla had stopped planting native corn varieties. They had instead opted for hybrids peddled by transnational companies and subsidised by the government. It’s a story repeated across rural Mexico, where economic and political factors have converged to push smallscale farmers into dependence on agro-industry.

Now this region is reviving native corn varieties and creating local jobs. In a town decimated by out-migration, multiple generations are discovering that corn could be the key to rejuvenating their rural community. “I wanted to create something of substance,” says Laposse. “I wanted to solve some of the problems facing Mexico, even if at a tiny scale.”

Tonahuixtla is in the Mixteca, a mountainous region of south-eastern Mexico spanning parts of the states of Puebla, Oaxaca, and Guerrero. The people of Tonahuixtla are indigenous Mixtec, a civilisation that flourished in the 11th century. While few people in the town still speak Mixteco, vestiges of the ancient culture remain: recently two Mixtec stone carvings were found in a field. During colonisation, the Spanish robbed the Mixtec of their native lands and founded haciendas throughout the region. It wasn’t until after the Mexican Revolution that the indigenous people recovered their lands. Tonahuixtla was founded as an ejido in the municipality of San Jerónimo Xayacatlán in 1942. Ejidos are towns where land is owned communally, a part of the agrarian reform implemented after the revolution. A colonial-era church sits at the centre and the residents number 700. Agriculture, on which Tonahuixtla relies, involves hard and unreliable work on the town’s steep hillsides, where rain is scarce. “Here in Tonahuixtla, you can grow almost anything,” says Lucía Dimas Herrera. “The problem is, there is barely any water. With water, this would be a paradise.”

“Here in Tonahuixtla, you can grow almost anything. The problem is, there is barely any water. With water, this would be a paradise.”

— Lucía Dimas Herrera

Dimas became ejido president last November and is one of the first women to hold the position. Like many Tonahuixtla residents, she boasts about the dozens of edible plants and crops that grow on the land: cactus fruit, squash blossoms, cherries, native olives, dates, coconut, mango, soursop and an edible seed called huaje.

Despite this bounty, agriculture in Tonahuixtla has become more difficult. Erosion and desertification were set in motion in the Mixteca centuries ago when the Spanish introduced intensive agricultural techniques, and goats and cattle that degraded the land. In the summer, heavy rains wash down the hillsides and wipe away vegetation. Without reliable irrigation or precipitation, crop yields are low and, according to the United Nations Environment Programme, Mexico loses an average of 870 square miles of arable land every year to desertification.

In the 1970s, people began to leave Tonahuixtla. Martínez was one of them. “I have always worked the land,” he says. “But in 1979 I went to the city, because there wasn’t a way to make a living anymore.” Martínez found work in Mexico City, but stayed deeply involved in his community. As an ejidatario, or rights-holding member of the ejido, he attended monthly assemblies and contributed to projects. “I always kept up with my responsibilities and helped out in the faena [communal workdays].”

In Mexico City, Martínez met Laposse’s father, a baker, who employed both him and his wife Maria Martínez. One summer in the 1990s, Laposse’s father agreed to send him and his sister to Tonahuixtla to get away from Mexico City, which was highly polluted and going through a crime wave.

Today, Tonahuixtla still does not have mobile or internet service. But in the 1990s it felt even more remote. Families boiled water over wood-fired stoves and hunted for sustenance. Tortillas made by hand from native corn accompanied every meal. Laposse visited Tonahuixtla over several summers. But when he was a teenager, his family moved to France and he went on to study in London at Central Saint Martins. A decade went by without him going to the town.

Meanwhile, agriculture in Tonahuixtla was undergoing rapid changes. During the 1990s and 2000s, many farmers stopped planting native corn varieties and began buying non-indigenous seeds, a process that had begun decades earlier. The Green Revolution, sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation, began in Mexico in the 1940s and became a worldwide movement to promote high-yield crops dependent on ample fertiliser use. It promoted hybrid seeds to increase food production, in place of traditional heirloom varieties. Falling into step, the Mexican government adopted subsidies that favoured hybrid over native seeds.

Hybrid seeds are bred to grow bigger and hardier plants, but they have downsides. They can only be used for one year, so a new batch must be purchased the following season; heirloom or native varieties are open-pollinated, meaning farmers can save seeds and re-plant every year. Hybrids also require heavy pesticide and fertiliser use. As a result, farmers became dependent on costly seeds and fertilisers and many went into debt. The already over-taxed lands of the Mixteca were drained of nutrients.

Economic changes in the 1990s, including the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), accelerated the shift to hybrid crops. Enacted in 1994, NAFTA devastated Mexican corn farmers, who suddenly faced direct competition from producers in the US Midwest that operated with significant subsidies and technological advantages. Corn imports from the US increased four-fold after NAFTA, according to Subsidizing Inequality: Mexican Corn Policy Since NAFTA, a 2010 study from the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

The Mexican diet changed dramatically. Cheap imports flooded the market, replacing homemade corn-based dishes with processed foods. Rates of diabetes and obesity soared. Meanwhile, farmers who couldn’t compete with American agro-industry were often forced to abandon their small towns. Many rural, indigenous Mexicans displaced from the agricultural regions decided to head north. Migration to the United States rose 79 per cent from 1994 to 2000.

Puebla is one of the Mexican states with the highest rates of migration to the US. People from Tonahuixtla have migrated to New York, California and other states in search of work. Two of Dimas’s sons live in Los Angeles. “People see opportunities elsewhere, so they forget their homeland,” says Martínez. “That’s why so much land has been abandoned.”

* * *

Genetically modified organism (GMO) crops are the next frontier, with the US agro-chemical corporation Monsanto being their biggest proponent in Mexico. Unlike hybrid varieties, GMO seeds combine material from plants that cannot traditionally be bred together. As such, they require splicing genes in a laboratory.

When Laposse attended an artists’ residency at the Centre for the Arts of San Agustin (CASA) in Oaxaca in 2015, GMOs were on the tip of everyone’s tongue. Noted Oaxacan artist Francisco Toledo founded CASA in 2006 and was at the heart of the GMO debate that coursed through communities in the region. At around the time it became particularly intense, Laposse began a project focused on maize and rural Mexico.

This was before January 2017, when a Mexican court held up a ruling that Monsanto could not pilot genetically modified corn in Mexico, due to its environmental impacts. Since then, both agricultural and scientific experts named to the new federal administration that took office in December 2018 have spoken against GMO crops. The evolutionary developmental biologist Elena Álvarez-Buylla, for example, has been appointed the new director of the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT) and has been vocal in her fears that genetically modified corn could spoil Mexico’s agricultural biodiversity. “I’m not a Luddite who is scared of technology,” she told Science in October 2018. “If a transgene is inserted in one part of [a plant’s] genome, it can be silenced and have no effect. If it’s inserted in another part, it can lead to a tremendous change.”

Instead of just delivering an artistic statement about corn and genetic diversity, Laposse wanted his design project to make a difference in the lives of farmers. The rich blues, yellows and reds of native corn husks caught his eye. Hybrid corn is bred to be uniform, whereas the indigenous plant varies from town to town. “That’s when it clicked for me,” he says. “There’s a huge potential in presenting the husks in an elevated way that would give corn added value for farmers.”

Remembering the vibrant corn of his childhood, Laposse planned to visit Tonahuixtla and explored whether he could work with the farmers there to make objects from corn husks. Martínez had moved back to Tonahuixtla for good, so his old friend went to find him. “When I went back, it was a shock,” says Laposse. “They didn’t have the corn I remembered anymore – they were planting hybrids. Most of the kids I had known had grown up and gone to the United States.”

His timing was fortunate, however. Martínez was working with León to encourage organic practices, including worm compost, and reforest an area of communal land with cacti and maguey. Out-migration had taken its toll on the community, but they thought that reinvigorating agriculture might offer a way forward.

“Around 2013, we started planting with more organic methods, and making our own worm compost to use on the pitaya [cactus fruit], lime and mangos,” says Martínez. “In 2015, Fernando came back and started talking to us about Totomoxtle.” Martínez and León were receptive to Laposse’s proposal. The London-based designer and the Puebla farmers began to work together. Totomoxtle, which means corn husk in the Mexican indigenous language Nahuatl, was born.

* * *

Since studying product design at Central Saint Martins, Laposse had been fascinated by natural materials. But it was outside the classroom that this interest flourished. An apprenticeship with the British designer Faye Toogood in 2012 cemented his love of handmade materials derived from the natural world. In his first independent projects, he experimented with making glassware from sugar and later, turning fat trimmings from London butchers into soaps. “Through those projects I identified the problem of waste,” says Laposse. “And the fact that all these old techniques have been lost.” Working with Bethan Laura Wood, another London-based designer, from 2011 to 2012, Laposse learned the craft of marquetry. These elements of his practice converged in Totomoxtle.

Laposse found that corn husk shares many characteristics with wood: it retains its colour after it is cut from the plant and, due to its fibre structure, it can be flattened or bent. But for the project to be a success, the first challenge was procuring colourful corn husks. For that task, León’s expertise was instrumental. His family is one of the few in Tonahuixtla that preserved their indigenous seeds through decades of upheaval. He had inherited native corn, bean and squash seeds from his parents. “My father liked his corn, because it yields a lot of dough and is very resilient,” León explains. “It survives hot weather and droughts.” These traits are the result of centuries of careful selection. “I’ve seen that hybrid seeds don’t survive when there is little rainfall,” he says. “People actually come from other towns to buy my native seeds.”

“When people see that there is an added value to their crop they start doing better.” — Denise Costich

Although suited to the dry climate of Tonahuixtla, León’s seeds were not plentiful enough to supply Totomoxtle. The farmers experimented with other varieties, but the project’s first corn harvests were insufficient. Laposse scrambled to find enough husks for the early rounds of production.

That’s where Denise Costich came in. Costich is the head of the Maize Genetic Resources Center at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in Texcoco, Mexico. When she heard of Totomoxtle, she contacted Laposse immediately. “I was really excited when I heard about Totomoxtle, because I knew it could directly benefit small farmers,” she says. “And it’s a fantastic use of maize diversity.”

CIMMYT has 28,000 samples of corn seeds from 83 countries. The collection began in the 1940s and has been housed in Texcoco, a mid-sized city outside Mexico City, since 1966. CIMMYT was, in fact, the main proponent of the Green Revolution in Mexico. Today, however, the maize germplasm bank seeks to reconnect small-scale farmers with native corn varieties and preserve genetic diversity. Mexican corn is divided into 59 landraces, which are genetically distinct types of corn. There are then countless variations on these landraces, created by seed saving and selection. After contacting Laposse, Costich and her staff identified seeds from areas like Tonahuixtla: sub-tropical, midaltitude. For the staff of the maize bank, exploring corn-husk shades was a novel experiment. “There are husks of all different colours, but we weren’t collecting data on that before,” says Costich. Now CIMMYT has begun to gather information on cornhusk characteristics.

Costich says Totomoxtle is a model for how communities can maintain genetic biodiversity in their corn crops. By creating alternative income streams based on corn, farmers have an incentive to grow native varieties. “Native corn doesn’t have the same support and subsidies that hybrids do, but when people see that there is an added value to their crop they start doing better,” says Costich, who adds that the broad participation in Tonahuixtla, which includes everybody from teenagers to septuagenarians, bodes well. “We’re at a critical moment. The landrace farmers are mostly old,” she says. “In terms of biodiversity we’re still doing okay. But the intergenerational shift will be crucial.”

The seeds from CIMMYT were first planted in 2018, with impressive results. There was finally a steady supply of yellow, purple, red and blue corn husks for Totomoxtle. Of more than a dozen varieties planted in 2018, the farmers in Tonahuixtla have selected four to use in 2019. The farmers and Laposse had to consider a number of characteristics. Varieties with colourful leaves that cover the full length of the cob are best. They also kept in mind the corn’s quality for food. “The important thing is that the corn stays in the community to eat,” says Laposse. “Totomoxtle uses what would otherwise be waste.”

* * *

As Totomoxtle began to bear fruit, more townspeople joined the effort. Laposse travels back and forth from London to monitor the process and bring back completed objects for sale. Communication is challenging – Tonahuixtla has only a few land-line phones and no mobile coverage. Despite these difficulties, however, Dimas, the ejido’s president, says that reviving native corn will have multiple benefits. “We’re recovering a lot of things that were lost in our community,” she says, sitting outside the ejido’s meeting house. “Now, people eat a lot of junk food. We’re trying to motivate our community to return to healthier habits.” Dimas adds she has always preferred making her own tortillas, even as she raised four children singlehandedly. “With all the resources we have here, how is it possible that we’re eating foods that harm us?” she asks.

But there are still significant barriers to adopting native corn. For one, many businesses have grown accustomed to hybrid varieties. Middlemen from tortilla shops come to Tonahuixtla to buy up corn. These “tortilleros”, as they are known, prefer homogenous white varieties grown with hybrid seeds. León García says that when he has tried to sell native corn to them, they balk at its range of colours, shapes and sizes. Now the town is exploring other buyers, such as a restaurant in San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, which recently bought native corn from Tonahuixtla. Such businesses pay a better rate than the local tortilleros.

But the land in Tonahuixtla is still dry and difficult to cultivate. Since 2013, Martínez and León have been making worm compost to use on the exhausted soil. The project has restored nutrients and improved yields. Even so, erosion is chipping away at the land. As a result, ejidatarios have banded together to begin reforesting an area of communal land known as El Limón. The project received funding in 2017 from Mexico’s forestry commission. León and Martínez led a group of ejidatarios to dig contour ditches, which capture rainfall. They also planted maguey to prevent erosion.

Walking through El Limón, jagged rocks jut out of the ground and the thin soil cover is parched, with months until the rainy season will begin. “Instead of trees growing, we have rocks growing here,” jokes Martínez. It is slow work, but through reforestation and organic agriculture, Tonahuixtla residents are gradually restoring fertility to their arid farmland.

* * *

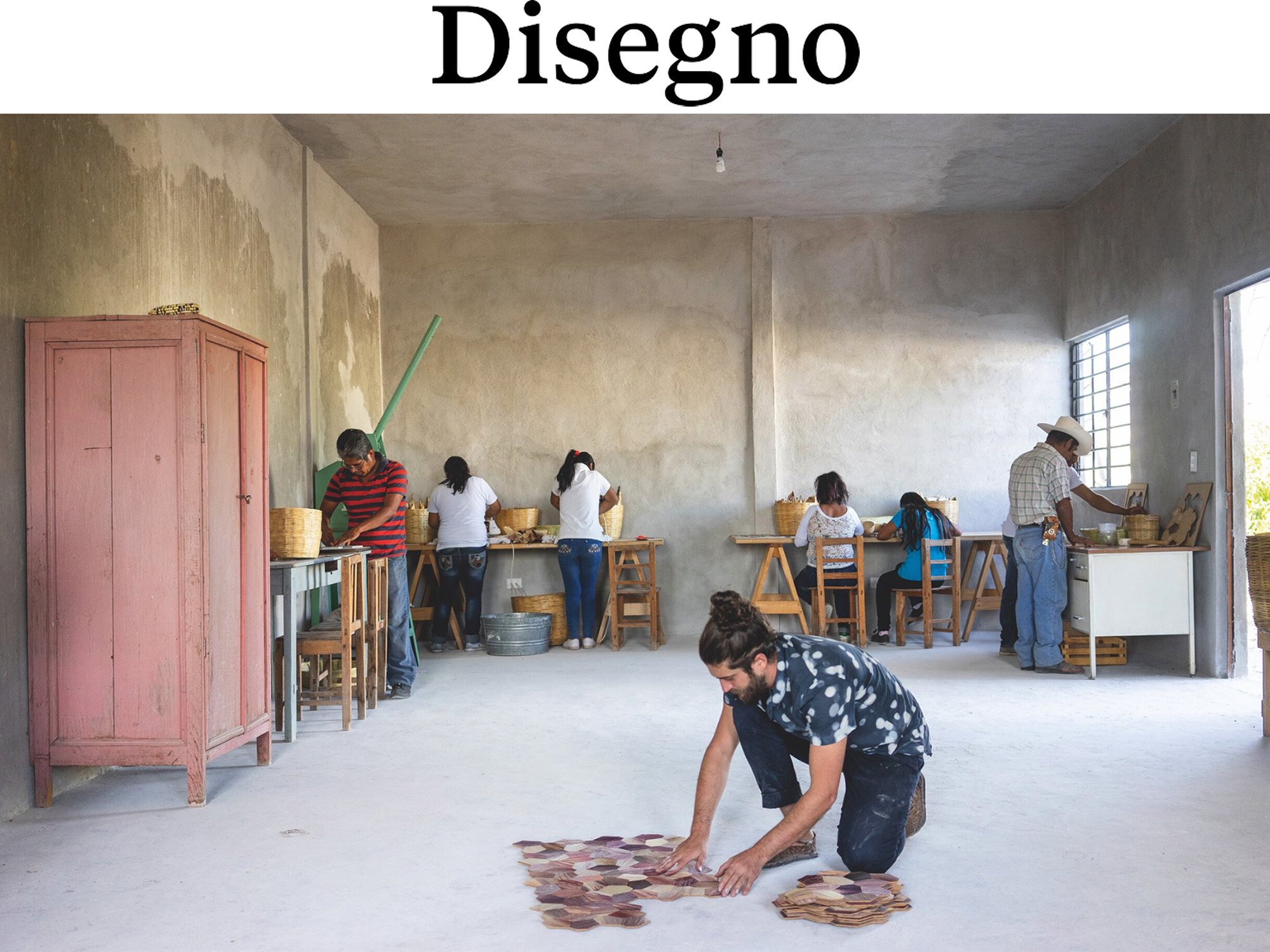

Growing the corn is just the first step in creating functional design objects for Totomoxtle. The production process is painstaking. In the afternoon, after the planting, a team of seven gets to work in the ejido meeting house. They iron the corn husks, paste together the pieces to create veneer, press the husks onto cork backing and snip delicate shapes of different colours.

It’s a process that Laposse has refined through trial and error, prioritising the participation of local residents. Constant tinkering led to a method that highlights the natural colours of the corn husks, while creating durable and attractive design objects. “Now, we’re trying to scale up with the material,” he says. “I want to go for quantity, with the condition that the employment stays in the community.” Starting out, he would assemble pieces in London when he received a commission. But it’s time-consuming work that he would rather employ people in Tonahuixtla to do: “Now, once the pieces leave Tonahuixtla, they are almost entirely fabricated.”

Efficiency is sacrificed for ethical congruency. Reducing waste takes on new significance in Tonahuixtla, where there is no public refuse collection and rubbish is usually buried or burned. Laposse says that they were originally using a glue that came in plastic bottles, but when these bottles piled up, the workshop employees asked him to reconsider. He found a new heat-based adhesive that produced less waste.

The only part of the process that requires electricity is one of the initial steps: ironing the husks. Even so, Laposse says they sometimes blow out the electricity at the workshop with this simple task. “There are all sorts of challenges to [keeping production local], but for me it’s a question of principle,” he says. “There is such a frustrating social and economic gap in Mexican society and that gap needs to be closed.”

The young men and women who make Totomoxtle objects now have reliable, well-paid employment. “I like working on the project because you see part of our culture that we don’t take advantage of,” says Fany Arllec León Ramos, one of the townspeople. “We’re showing other people our Mixtec culture.”

“There is such a frustrating social and economic gap in Mexican society and that gap needs to be closed.” — Fernando Laposse

Laposse prefers to share the design and production methods so that they can be widely adopted, instead of guarding them as his intellectual property. To truly socialise the process in Tonahuixtla, he says he disregards the usual timeframes that designers work with. “I want to design in systems, to build the whole process from planting to harvesting. Too many designers are caught up in the rush of new things. But to really be sustainable you have to respect the cycles of nature and slow down.” Totomoxtle has already received accolades, including the Future Food Design Award at the 2017 Dutch Design Week. Laposse put the prize money towards expanding the agricultural project in Tonahuixtla.

* * *

Two weeks after the corn planting, Laposse is at the Archivo de Diseño y Arquitectura (Archive of Design and Architecture) to inaugurate his first solo exhibition in Mexico City, Transmutations. Martínez and his wife Maria are among the Tonahuixtla residents who travelled to the capital to see the work fashioned from their town’s corn on display.

Guests sip mezcal cocktails in Archivo’s courtyard, filled with lush ferns and trees, until they are ushered into the gallery space. Laposse, Martínez and Costich take the floor. Martínez, a practised public speaker from his time as Tonahuixtla’s community president, graciously greets the audience. “I’m here to talk about the countryside,” he says. “Our countryside has been abandoned in Mexico[…] but last year we harvested our own native corn. And most importantly, we have the coloured husks for Totomoxtle.”

The exhibition displayed not only the elegant objects of Totomoxtle, but the years-long process to reach this point, so that a corn farmer could stand alongside a designer at one of Mexico City’s most important galleries. As Mexico City’s art and design continues to attract global attention, Totomoxtle turns the gaze towards the nation’s small, rural communities, which are so often overlooked. Tonahuixtla represents the story of rural Mexico: how entire generations of farmers were forced to give up their traditional practices and seek work far afield. Now, Totomoxtle seeks to reverse the trend.

Laposse uses design to bridge the gap between urban and rural, rich and poor, creating both new forms of art and preserving his country’s rich heritage. “What’s at stake is our identity,” he says. “Mexico is amazing because it has so much diversity of people, lifestyles and traditions. There are so many Mexicos in Mexico. But they’re at risk of disappearing.”