By Hannah Martin

Is it art? Is it design? Who cares? In Wild Thing, the latest AD PRO column, senior design writer Hannah Martin discusses a thing that makes her heart sing.

Glossy, candy-slick finishes, fuzzy flocking, bubble gum barnacles. Walking into Homely, Chris Schanck’s shimmering show at New York’s Friedman Benda gallery (which opened on

March 1) is like entering some sort of underwater fantasy. “It’s very Little Mermaid,” Schanck admits.

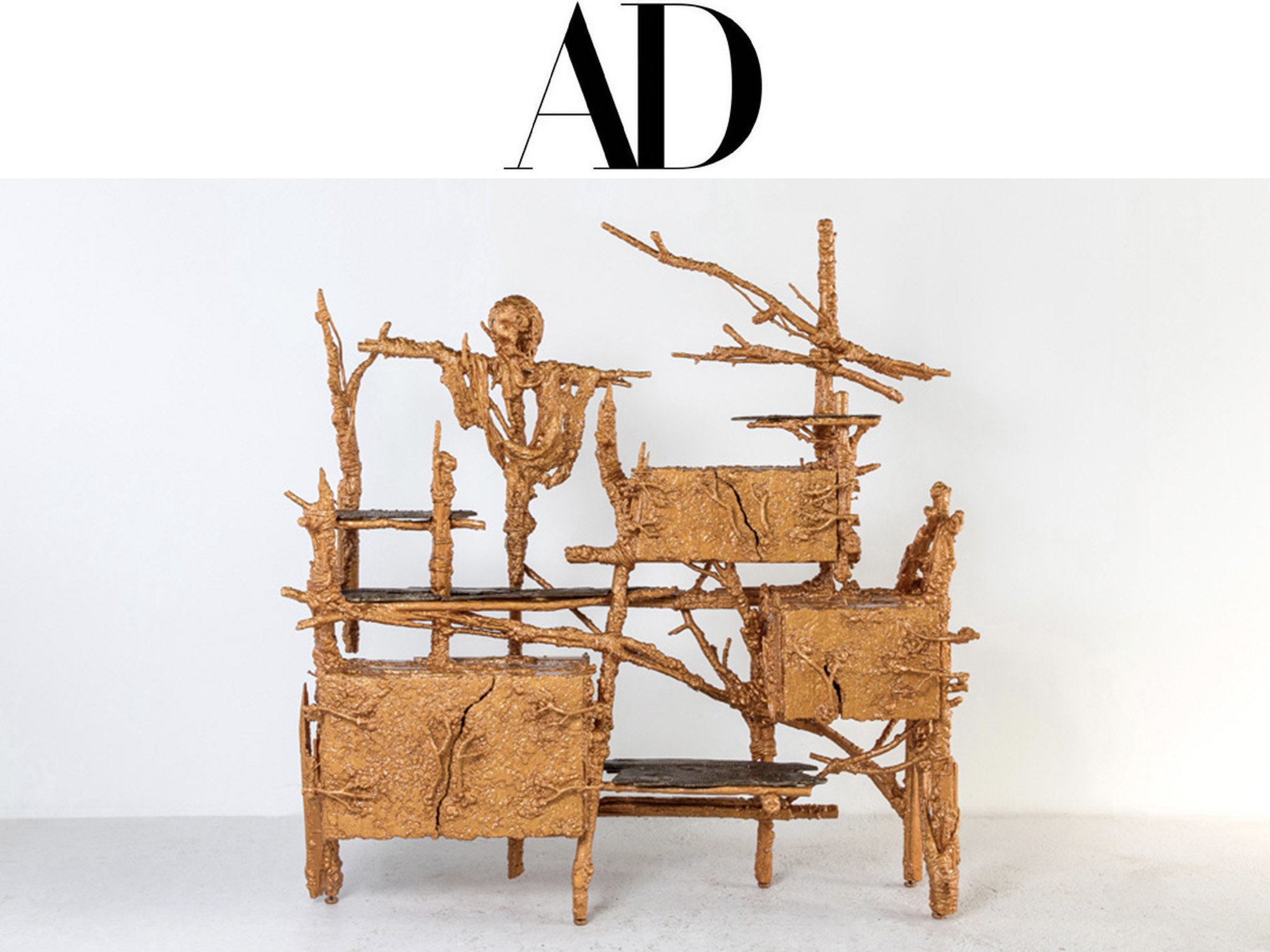

But there’s one piece—a stick-legged cabinet called Banglatown—that stands out from the group of lustrous, tactile treasures.

“It’s actually the one I’m most interested in,” says Schanck. “I wanted to make a piece about what I see in my neighborhood that inspires me every day.”

Schanck—who studied at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan and Central Saint Martins in London—came to Detroit by way of Cranbrook Academy of Art, where he majored in photography and 3-D design. After he set up a studio post-graduation in 2011, his eyecatching Alufoil series—furnishings made from discarded materials covered in aluminum foil and shellacked in resin for a look of high-gloss industrial decay—quickly gained a fashionable following. Architect Peter Marino commissioned an Alufoil bench for a Dior boutique in New York. Designer William Sofield placed a desk and chair in the Tom Ford flagship on Madison Avenue. New York’s Friedman Benda and Paris gallery Almine Rech added him to their rosters. But while Schanck’s practice falls in conceptually with a crop of young designers (Misha Kahn, Katie Stout, Chris Wolston), making clumsy-looking, sometimes-ugly furniture that challenges ideas of functionality and good taste, operating outside of the New York/Brooklyn scene has kept his studio comparatively out of the spotlight.

After all, a studio visit to Schanck’s involves a bit more planning for coastal design hunters. His home and workshop is situated in Banglatown, a neighborhood in Northeast Detroit where the single-family homes built in the 1920s and ’30s for automotive industry workers have been repurposed by a vibrant community of Bengali people. Seven of them work in his studio as finishing experts, clocking thousands of hours masterfully applying foil to his creations.

“They have collectively invented their own tools and techniques for the process, and when a new member enters the group, they undergo an informal peer-to-peer mentorship to learn the idiosyncratic process of the work,” says Schanck, who is quick to admit that “their skill set has surpassed my own in this regard.”

Schanck soon noticed that the same skillful handiwork and make-do spirit of his studio hands on full display in the Bengali gardening system—the inspiration behind his new cabinet. “Every single Bengali family gardens in this very unregulated way that I don’t think you could get away with anywhere else,” says Schanck. “Front lawns, alleyways, rooftops, public private spaces. They take over whole abandoned lots and build infrastructures for them with collected materials from their area. No one’s going to Home Depot for lumber. They don’t have screws; it’s just bound and tied.”

To pay tribute to the community, Schanck constructed his own rendition of the gardening infrastructure, built for the vertical cultivation of squash and beans. As with most of his

pieces, he worked with a steel fabricator to create a basic form which was then built out with wood and other fragments foraged from the neighborhood. The amalgamation of stuff was then coated with epoxy, an encasement of foil, and then another coat of epoxy. To turn it into a functional cabinet, he cast sheets of corrugated cardboard in bronze for shelves, and lined cabinets with bronze-leafed cowhide. For its crown, Schanck worked with his neighbors to make one of their signature scarecrows: “The scarecrows are the best thing in the neighborhood. They’re so terrifying.”

The piece represents, in some ways, the next step for Schanck. He’s moving into something more narrative and nuanced, exploring figuration in a real way. Rather than using experimental materials and processes to telegraph dreamy, supernatural worlds, here he’s telling a very direct story about the one we’re in.

Says Schanck: “A lot of my work is otherworldly and fantastic. But this piece starts to ground it in reality.”