By Malaika Byng / Photographs courtesy Chatsworth House Trust/India Hobson

An exhibition continues a tradition of commissioning avant-garde work begun by the Duchess of Devonshire in the 1950s

When visitors roam the gardens of Chatsworth House in Derbyshire this weekend, they will find a new perch on which to sit and look at the stately pile. Made from grit stone from the estate’s quarry, the bench is patterned with grooves, hand carved by a stonemason with the guidance of an augmented reality headset and filled with a substrate that encourages mosses and lichens to grow in its shaded recesses. Over time, nature will add to this design object, bringing a soft green and yellow upholstery to its computer-generated pattern.

The Symbio bench by Dutch designer Joris Laarman positions nature, man and technology as collaborators. “For too long architects and designers have tried to keep nature at a safe distance, but we need to find ways to incorporate it in everything we create,” he says. “There’s no other way forward.”

Laarman’s design, cut from the same stone as the Baroque house, references the site’s history while pointing to the future. It provides an apt spot for contemplation as part of a new exhibition, Mirror Mirror: Reflections on Design at Chatsworth, which aims to connect with the continuum of contemporary art and design commissioning by the Cavendish family, who have lived at the house for 16 generations, while addressing current social and environmental concerns.

“The exhibition is a dynamic conversation between the past, present and future,” says Chatsworth’s senior curator Alex Hodby.

Britain’s ancestral homes have had a difficult tussle with modernity. They were once showcases of the latest fashions in design, art and architecture, but they began a steep decline during the industrial revolution, before high death duties and wartime requisitions in the mid-20th century saw many families abandon their country seats and sell off their contents. Those that survived have faced a challenging negotiation between preservation and moving with the times.

Chatsworth House, built in the 16th century and almost entirely rebuilt in the 17th century, has fared better than many, however. It is thanks to the foresight of Deborah Mitford, who married into the Cavendish family in 1941. When her husband inherited the title of the Duke of Devonshire in 1950, along with a hefty tax bill, she took action.

While other stately homes were becoming tired repositories for rusty armour and creaky antiques, the Duchess reimagined Chatsworth as a tourist attraction and economic hub, equipped with a farm shop and cutting-edge art and design, including family portraits by Lucian Freud — a radical move at the time.

“She was a true entrepreneur and a risk taker,” says Jane Marriott, the new director of the Chatsworth House Trust, which manages the property. “She set the tone for the next generations.”

The current Duke has built on his mother’s legacy, continuing to commission makers — including ceramic artists Edmund de Waal and Jacob van der Beugel, and furniture maker Joseph Walsh. While the house, gardens and park have been run by the trust since 1981, the family continues to shape its collections and exhibition programme.

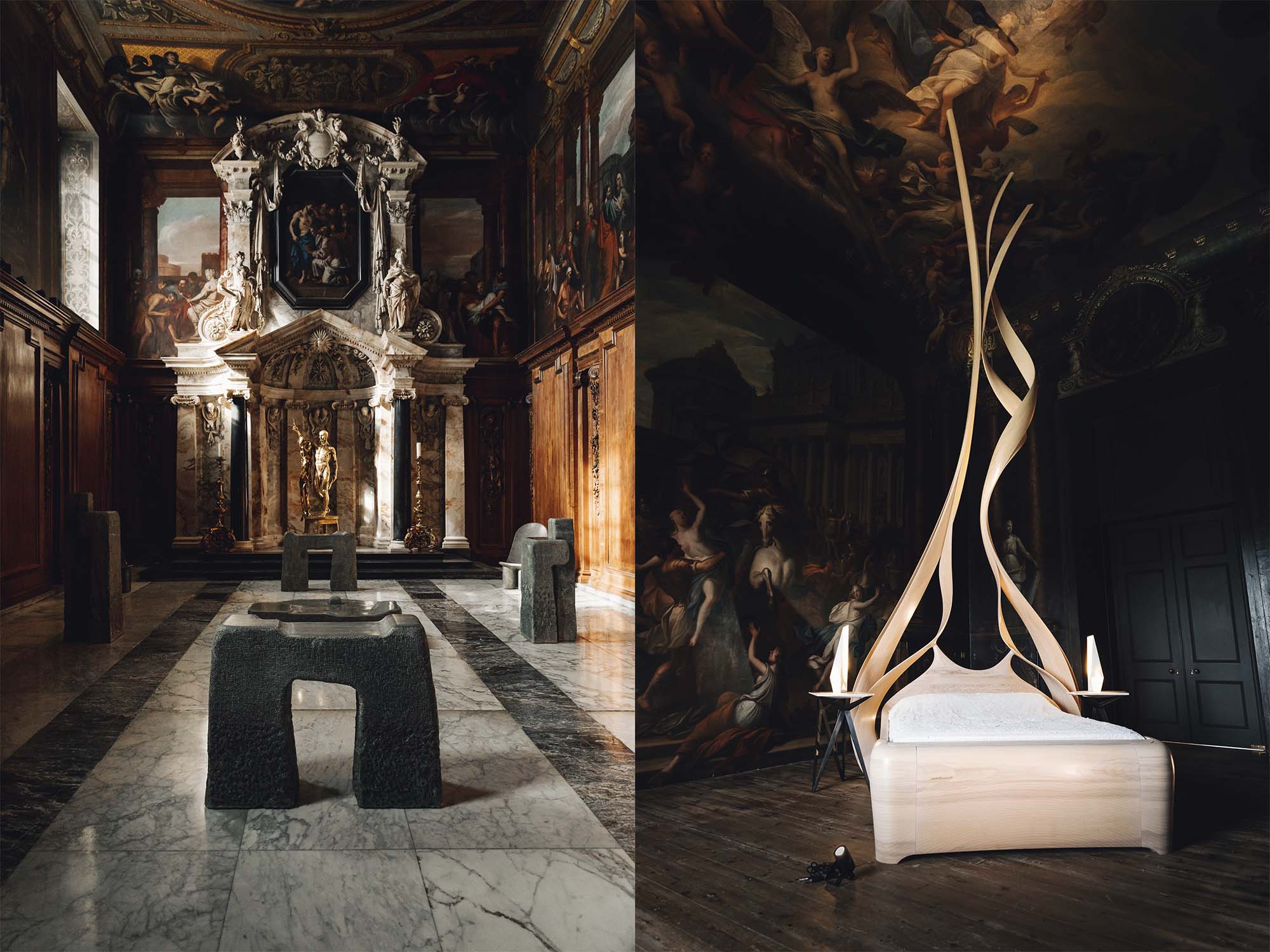

For Mirror Mirror, Walsh’s steam-bent, wooden Enignum VIII Bed has been relocated to the West Sketch room, its twisting folds echoing the drapery in James Thornhill’s 1707 mural “The Rape of the Sabine Women” on the ceiling above.

The show comes at a moment of transition for Chatsworth, with the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire moving out, their son and daughter-in-law, Lord and Lady Burlington, moving in, and a new director at the helm of the trust. This change offers a chance to rethink what Chatsworth can offer its 600,000 visitors a year.

“There’s an opportunity for country houses to play a significant role in times of economic and environmental crisis,” says Marriott. “Chatsworth can provide a moment of respite from daily challenges, and inspire its many visitors to do their own small positive acts. We need to bridge the gap between history and what’s happening in the world right now.”

Mirror Mirror seeks to connect them, while offering moments of introspection. Laarman’s bench, for example, draws on Chatsworth’s material history while asking people to reconsider their relationship with nature as they rest. The design is the first piece in a new body of works he is developing.

US designer Chris Schanck, meanwhile, extols the virtues of upcycling by transforming scrap materials into crystalline forms, using iridescent resins. Their complex surfaces are in dialogue with the ornate carvings in Chatsworth’s grotto.

Since the late Duchess’s day, contemporary art and design exhibitions have become de rigueur in Britain’s stately homes as a way to pull in the crowds. Chatsworth isn’t immune to attention-grabbing shows — the grounds played host to sculptures from Burning Man festival last year — but Mirror Mirror is conceived as a more subtle experience.

“We’ve taken inspiration from Edmund de Waal’s use of the term ‘site sensitive’, rather than ‘site specific’, to describe his installations,” says co-curator and author Glenn Adamson. The exhibition is not about contrasts between old and new. As Hodby puts it, “If you try to compete with the interiors, you’re never going to win.” Instead it provides a series of encounters to help visitors see their surroundings anew.

US-born, Swiss-based designer Ini Archibong has reanimated the musicians’ gallery by composing a sound piece with a futuristic spirit. Nearby, his handblown glass Dark Vernus I chandelier sheds new light on two 19th-century bronze busts of a black man and woman by the French sculptor Charles-Henri Cordier.

“My goal was to create objects that feel committed to the spaces and resonate with them” — Faye Toogood

“They come from a period when France had an extremely problematic and complicated relationship with Africa,” says Adamson. “These sculptures exoticise [their subjects] in some way, even if they’re not overtly stereotyping. We thought the chandelier would create a great condition for viewing them, without being accusatory or bluntly political.” The viewer is left to connect the dots.

An exploitative relationship with Africa is an issue for many of the UK’s grand country homes, with several built or bought with money amassed from the slave trade. In Chatsworth’s case, the Cavendish family’s wealth was acquired largely through land purchased in the 16th and 17th centuries and no published connections to slavery have been found. But the trust is aware of the complex intertwining of wealth, power and colonialism. “It’s something that we’re having to research further,” says Hodby.

Some designers have produced one-off works for Mirror Mirror, while others have created new pieces in their own design language or the curators have selected existing examples of their work.

British designer Faye Toogood responded to the chapel with sculptural seating that recalls the Neolithic stone circles around Chatsworth, discovered through archaeological research.

In the Oak Room next door, she has referenced the ornate wood panelling installed by the sixth Duke of Devonshire in the 19th century, creating tables and stools from bog oak. “I wanted them to feel like relics,” she says. “My goal was to create objects that feel committed to the spaces and resonate with them.”

In the state closet — historically one of the most private spaces in the house — the British artist Ndidi Ekubia has pushed the craft of metal-raising to its limits, with a series of silver vessels with fluid, rippling surfaces. They riff off the vast silver chandelier that dominates the space and the history of Baroque ornamentation in the house, while adding a contemporary rhythm to it.

For Ekubia, the exhibition holds up a mirror to the country’s making traditions. “We need new generations to understand the history of design and craft in this country to move forward or these skills will be lost,” she says. It is the reflective quality of silver that first attracted her to working with the material. “When you walk into a room filled with silverware, you see your image on its surface and you become part of the space,” she says.

This experience is the curators’ aim with Mirror Mirror. It uses contemporary works to absorb visitors in Chatsworth’s historic interiors while suggesting a new future for design.

Until October 1; chatsworth.org