By Paul Clemence

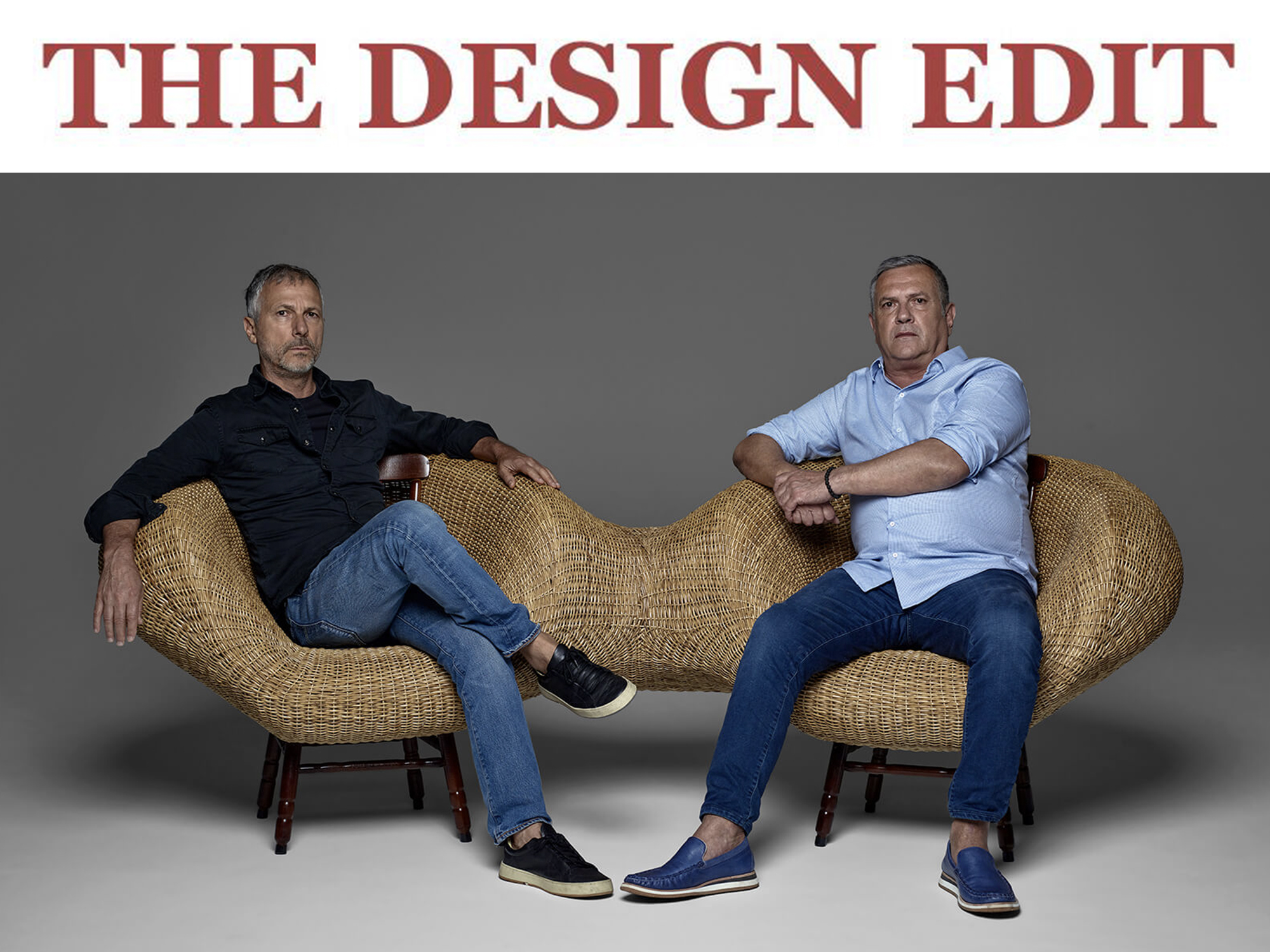

THE FIRST WORD that comes to mind when speaking with Humberto Campana, one half of the legendary design duo Campana Brothers, is ‘freedom’. First, of course, complete design freedom – iconoclastic, atypical, alternative, irreverent, ironic – everything is fair game in the brothers’ passionate fight against bland obviousness. But after 35 years of delivering creations that have seduced the design world (from renowned institutions and leading design galleries, to high end furniture and product makers), Humberto and Fernando have also reached a point of total freedom in how they pursue and – very importantly – enjoy their creative endeavours.

Their new exhibition ‘Campana Brothers: 35 Revolutions’ at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro (MAM Rio) is the broadest and most comprehensive showing of their work ever assembled. MAM Rio is deeply connected to conceptual and experimental art, and is one of the few cultural institutions in Brazil to recognise the relevance of showing design as an essential part of Brazilian history and culture. As the brothers were putting final touches to the exhibition installation, The Design Edit (TDE) had a chance to catch up with Humberto (HC) and talk about the environment, films, art, Brazil and the creative process.

TDE: How does it feel to have your work in this very special setting?

HC: It has always been a dream to show here. I have always loved this building, the modernist architecture of Affonso Eduardo Reidy surrounded by the Roberto Burle Marx gardens. This building is history, it’s an important part of Brazilian Modernity – but it’s also a hard space to occupy.

TDE: What were the challenges in installing your work?

HC: The space is open, with glass curtain walls, which meant that we had to black out all the glass walls so as not to compete with the beauty of the city outside – we could not win that competition! And we wanted to create an immersive experience for the visitor, as if in a dream or a film.

TDE: Films are an important reference in your creative process. Can we talk about the relationship between films and surrealism and how that translates into your work?

HC: We are storytellers. We take mental notes, mental pictures of things that we see, dream snapshots, and experiences that affect us – and we create from that. The unique materials we then choose to execute those ideas add yet another layer to the stories. Like ‘Sofa Boa’: it tells stories, it speaks of dreams, desires, of eroticism. I am inspired when I watch how transvestites and prostitutes dress at night, how these people – who are living on the margins – style themselves. I love going to a museum, but with these people there is a truth and freedom – there is beauty in that. Museums sometimes have censorship, especially in Brazil lately.

TDE: What are the filmmakers who have had a lasting impression on you?

HC: There are many … Fellini for sure – the way he would describe those characters, like in Amarcord, and “E la nave va” – it’s surreal, that scene with the plastic sea.

TDE: The Campana Brothers’ work is essentially very Brazilian, but not obviously so. Can you explain that?

HC: I think the Brazilianess is in our creative DNA. There is an intention. It’s in the blood, in our race: I am Brazilian, but I am also African, native Brazilian, Italian and Portuguese. Being Brazilian is being a hybrid being. Even if we touch the Brazilian cliché, it is about doing it with subtlety, a certain elegance, and irony.

TDE: Irony and humour are constant elements in your work.

HC: Yes, very much so. I think it might be a Latin thing. I identify a lot with the Pedro Almódovar films. I think we share a similar outlook on things.

TDE: Let’s talk about the concept behind the exhibition.

HC: We are creating a forest. There are 125 columns, each 2.60 metres tall, made of ‘palha piassava’ (a fibrous product of Brazilian palm trees), in the 120 metre-long space, which set the mood of the installation and organise the space for the different exhibition themes. The forest is a metaphor, a message, a call for attention to Nature, and a reminder that Brazil’s environmental richness is our Louvre, our Guggenheim, our British Museum! It is our cultural heritage! We want to draw attention to the need to protect and preserve that heritage.

TDE: The exhibition is also curated by an art curator, rather than a design specialist. How did you find that process?

HC: Yes, the exhibition is curated by Italian curator Francesca Alfano Miglietti. It has been a very collaborative process. Francesca gave us a lot of freedom. It feels like it has been an exhibition curated by the three of us, under her coordination, of course. We gave her a list of pieces we thought were important and she organised them in themes based on what emotions she felt the pieces suggested.

TDE: Right at the entrance you will feature a wall screen made of Brazilian breeze blocks. What’s the story of that piece?

HC: That project’s inspiration came after we visited the site of the mining accident in Mariana, Minas Gerais. The ‘Mão’ (‘hand’) bricks feature cutouts in the shape of a hand, as though they are reaching out – both protesting and asking for help. The original idea was to use the resulting mud from the accident, but that mud wasn’t structurally rigid enough. This project was initiated by our Instituto Campana with the Minas Gerais based non-profit Divina Terra, which has a focus on sustainable handmade practice of ceramic and wood craftsmanship.

TDE: The collaborations with the non-profit organisations which are the focus on the Instituto Campana have become an important part of your practice. Are there any of these collaborative projects in the exhibition?

HC: The non-profit from Rio de Janeiro, Spetaculu, founded by Gringo Cardia, is helping us with the installation of several parts of the exhibition – like the piassava columns, the ‘sky’ of string mandalas for the ceiling, and the screen PELE (Skin) that we are putting at the end of the exhibition. PELE is made of small clay stones attached to a wire mesh, from which vegetation will grow. This was inspired by the spontaneous flora we see sprouting in unlikely places here in São Paulo, like the side of a flyover concrete pillar. So, the exhibition opens with terracotta (the brick wall), and ends with terracotta, and in the middle a forest of piassava columns under a string sky! The idea is that all these materials could be re-used afterwards.

TDE: Is there any new piece in the exhibition that you would like to mention?

HC: There is the ‘Meteoro’ (‘Meteor’) line, which is made of the discarded cushioning Styrofoam pieces used to package large electronics. We have an armchair, a sofa and shelf made of that material.

TDE: As your practice expands deeper into more artistic creations, does functional design still interest you? How do you see that balance between design and art?

HC: Yes, always. One thing does not exclude the other. In our work we make bridges between these. It depends on the moment and on the circumstances. We are in a different moment from at the beginning of our career. We are at a moment where we desire to be free, not limited by labels, by functions, by pricing, or by the marketplace – a 35 year career means freedom. I quit being a lawyer to be free, it’s the path both Fernando and I chose. We’ve done so many things, we have earned that right to freedom. I think this exhibition will broaden our scope and open new possibilities. This exhibition has been like a dream for us, we’ve been working on it for a year, trying to connect all the dots, getting pieces from faraway places, finishing new pieces. It’s been a bit like pushing that boat in the film ‘Fitzcarraldo’, one metre a day. Putting this exhibition together has given us a lot of experience, it has been very empowering.

TDE: As opening date approaches, how does it feel to see it all come together?

HC: I haven’t thought about that yet, amidst all the adrenaline rush of making the exhibition happen. But as the opening day nears and all is coming together, I feel a certain lightness.