By Hannah Martin

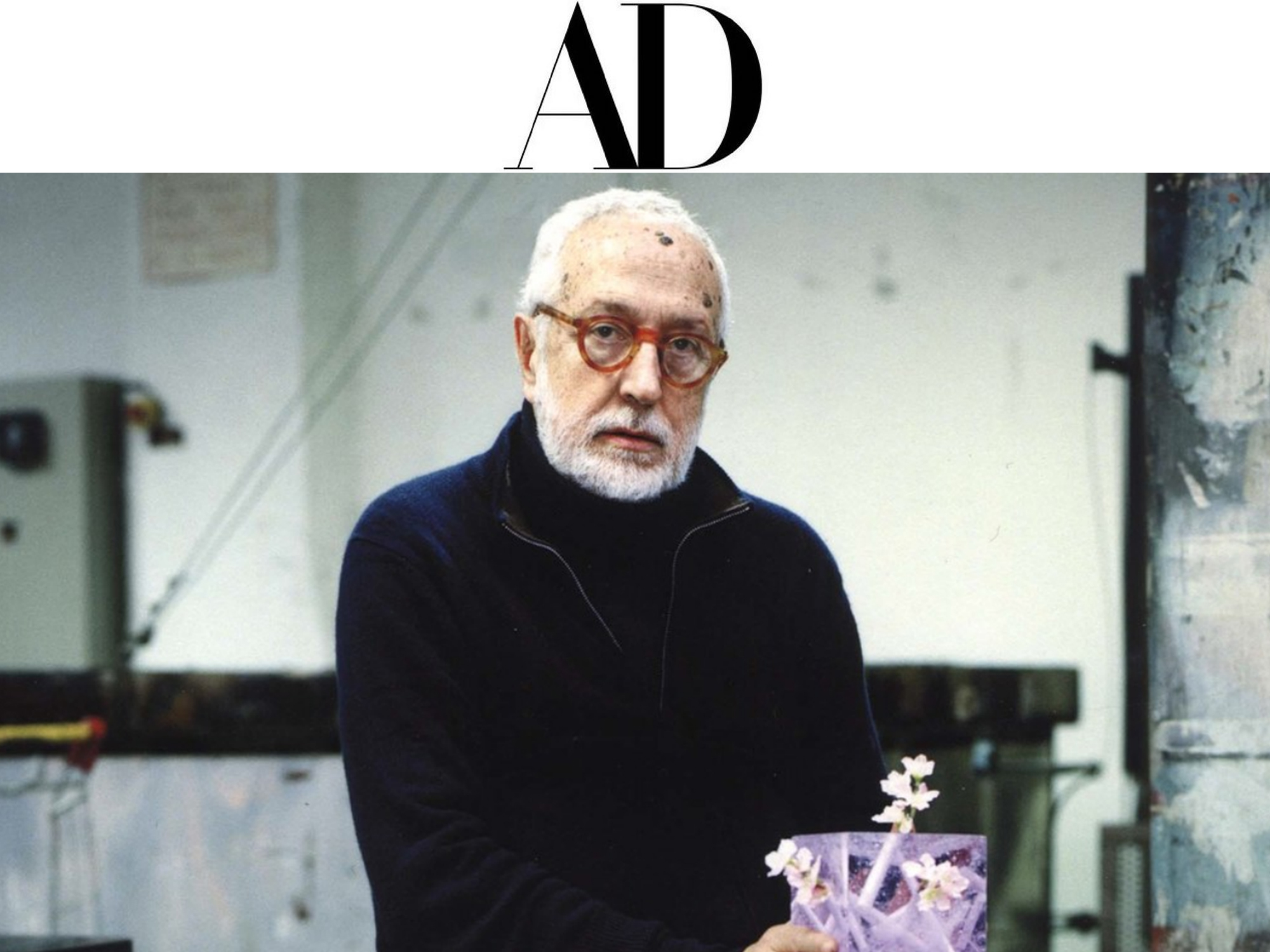

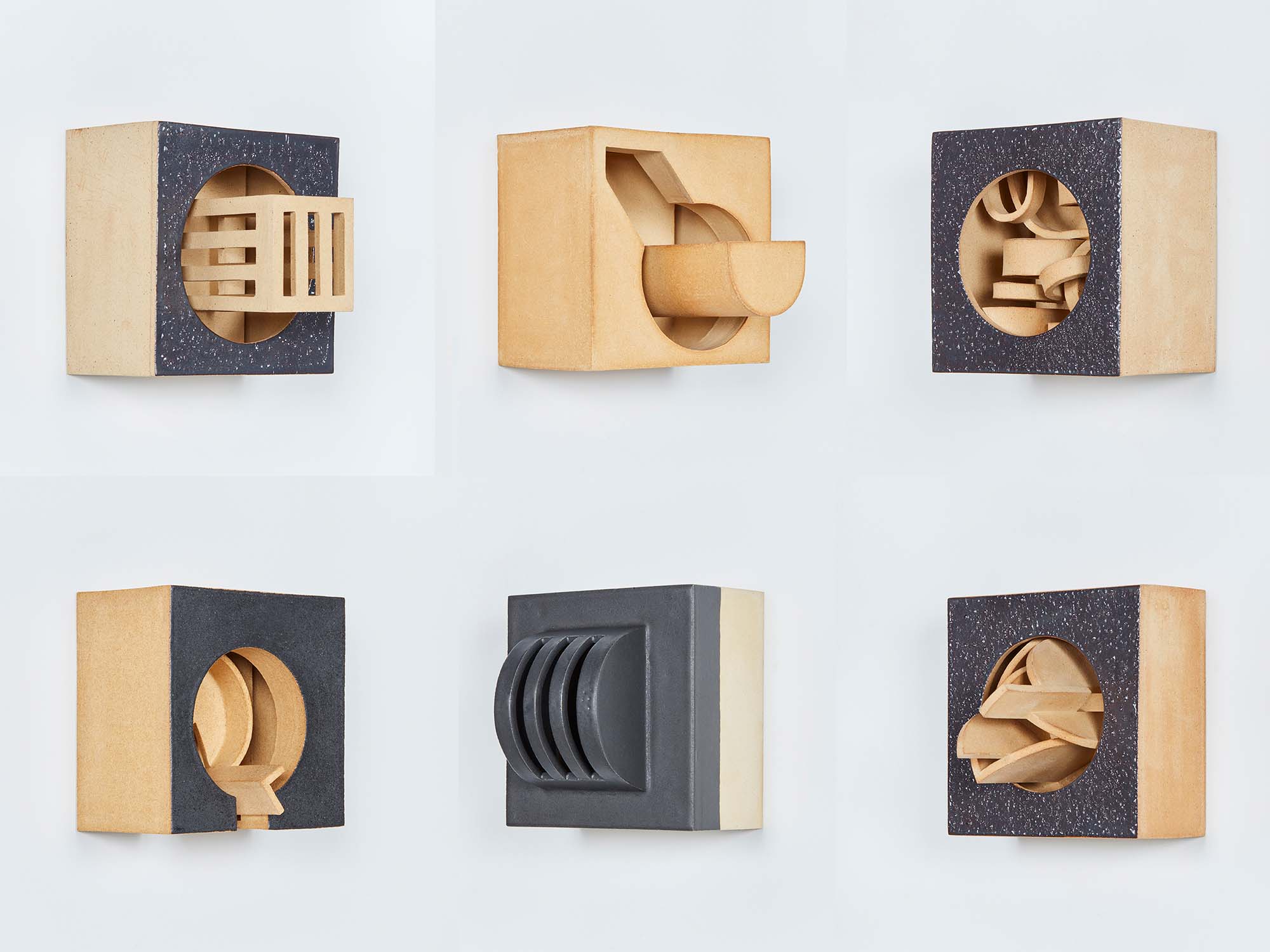

In 1985 the Italian architect, designer, and theorist Andrea Branzi, and his wife, Nicoletta, debuted a radical collection of objects. Raw birch branches were attached to a varnished wood base to make an armchair. Limbs sprouted from a simple MDF seat to create a woodsy perch. A stainless-steel lamp emerged from a tree trunk. The results—many of them resembling weird mash-ups of Adirondack furniture and IKEA Parsons tables—were called” Domestic Animals” (“Animali Domestici”), and they marked the debut of Branzi’s now-signature neo-primitive style.

“We had been investigating a new expressiveness of objects—objects that, like animals in the Amazon, were able to attract their partner through color, perfume, and decor,” reflects Branzi. “They didn’t try to interest everyone. They were experimental, artisanal prototypes that were destined (as it happened) to collectors and museums.”

He was on to something. More than 30 years later, it’s this sort of thinking that fuels the collectible design market—and this week’s destination design fair: Design Miami in Basel, Switzerland. Here, considering today’s taste for strange material studies and futuristic riffs on craft, a slew of one-of-a-kind and limited edition design objects are sure to attract and repulse in equal measure. Among them, at the booth of New York gallery Friedman Benda, five works from the “Domestic Animals” series will be shown as part of “Andrea Branzi: Genetic Metropolis,” an expansive retrospective of Branzi’s work.

Branzi, who was born in Florence in 1938 and graduated from the Florence School of Architecture in 1966, always understood objects for what they were—commodities. Upon graduating, Branzi concluded that, to really engage with society, he should create things, not buildings: “Pop Art signaled that the world of goods had become central in the urban and human scenario,” he explains. “The city was flooded by merchandise, industrial products, and commercial activity, while architecture rested on its rigid and unresponsive foundations.”

But Italy’s economy left little if no funding for the subversive new superstructures the latest generation envisioned—a reaction to decades of Modernism that prescribed, in Branzi’s words “rationalism, functionalism, conformity, and the myths of a future in the order and discipline.” Branzi—and the radical Italian architects of his generation—found an outlet for their ideas in theory, printmaking, and furniture design.

In 1966, along with three colleagues, he founded Archizoom Associati, a research collective that responded to the monotony of Modernism with cartoonish Pop Art–inspired furnishings like the Superonda, a series of wave-shaped hunks of foam that could be assembled into a bed or lounge. Perhaps even more progressive was their No-Stop City project, a study in urbanism that suggested, with the advent of new technologies, the need for centralized, modern cities would become irrelevant.

“Its continuous grid, potentially endless structure, and infinite flexibility made it a prescient forecast of the internet,” explains curator Glenn Adamson in an essay he wrote for the Friedman Benda exhibition. “Archizoom foresaw the liberating potential of future technology, and its tendency to surface the dark side of human nature.”

Archizoom would dissolve in 1973, but Branzi went on to cofound such groups as Global Tools (at the offices of Casabella magazine) and then Studio Alchimia with fellow radicals Ettore Sottsass and Alessandro Mendini. In Alchimia, the trio commented on design history by cleverly redesigning iconic chairs—Marcel Breuer’s Wassily chair was given a camouflage upholstery; Gerrit Rietveld’s Zigzag was turned into a crucifix. In Branzi’s case, he turned works of fine art—paintings by Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, and El Lissitzky—into decor by shamelessly copying them, and designed and created furnishings in faux homage to modern masters (like Italian architect Adalberto Libera) with the postmodern mentality that they should not be reproduced.

There’s no denying the current fad for Italian radical design: New York gallery R & Company just mounted “Radical Living” in tribute to the movement, the 2017 Met exhibition “Design Radical,” examined Sottsass and his contemporaries, and a forthcoming exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston will showcase the postmodern design collection of Dennis Friedman. But as our craze for Memphis (yes, Branzi was part of that late-1980s movement too) and its wacky predecessors wanes, the “Domestic Animals” series rises to the surface. Less Pop, more primal, it feels more relevant now than it did at its introduction.

“He’s thinking about nature and culture,” Adamson says. “We’re in this situation of imminent environmental collapse. If you’re thinking about thoughtful considered ecology in designed artifacts, ‘Domestic Animals’ is the necessary starting place.”

A quick survey of the contemporary design world shows a variety of spin-offs, whether acknowledged or not: Misha Kahn’s cabinets, composed of intricately woven trash; Sam Stewart’s stick chairs, wrapped in black vinyl; Dozie Kanu’s rudimentary stools and lamps, hand-slathered in gritty concrete.

“I’ve geeked out on the ‘Domestic Animals’ series since I first saw it,” says Brooklyn-based designer Brendan Timmins, who created his own homage to the series (called Neoprimative Too and made in collaboration with textile artist Alexandra Segreti) for a recent chair show at the Future Perfect. “What jumped out at me was his juxtaposition of natural and manufactured materials,” says Timmins. “That was something that drove everything he did.”

Adamson thinks for many of the young designers toying with primal aesthetics, the connection is less direct. “Branzi is one of these billiard balls,” he explains. “You wouldn’t have Droog [the conceptual Dutch design firm launched in the 1990s] without Branzi, and you wouldn’t have the current aesthetic tendencies of people like Misha Kahn, Thomas Barger, [and] Jay Sae Jung Oh without Droog. He’s like a grandfather. He’s also the person that gives you the idea behind it.”

Even Branzi himself seems continually reinspired by the ideas in that 1985 collection. Much of his work after “Domestic Animals” draws on the same neo-primitive language: His 2010 “Trees & Stones” series mixes segments of birch trees with industrial metals to create cabinetry and shelves; his 2014 “Planks” are, once again, hybrids of natural elements and metals, but this time, they read more like paintings than furnishings. Even in his “Evolution” series, produced just last year, he creates work that nods to a new prehistory, using wood and stone again in conjunction with bright hieroglyphics that looks like cave art meets street art.

When the “Domestic Animals” collection launched, critic and theorist Pierre Restany wrote, “Branzi’s neo-primitivism takes into account mundane things, advanced technology, and a return to nature.” Branzi himself argued (prophetically) at the time that those silos are harder than ever to determine: “The distance between the natural world and the artificial world no longer exists today, because the latter has become second nature.”

Maybe that’s why today—in a high-tech world full of manufactured things—a wooden chair featuring an actual hunk of tree is more radical than ever.