By Richard B. Woodward

‘Lebbeus Woods, Architect” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art articulates several reasons why this cultish figure (1940-2012) deserves to be better known yet, perhaps without meaning to, also suggests as many reasons why he isn’t.

The two rooms of drawings, models and theoretical writings offer a hypnotic portrait of an American out of step in his later years with his age and profession. A space-age philosopher more enamored of the incredible than the doable, closer in his own view to a mal content firebrand like Friedrich Nietzsche than to any of his contemporaries, he seems to have spent more time as an adult composing aphorisms and manifestos than going about the tedious business of winning commissions or seeing that his fantastic schemes were actually realized. He leaves behind almost nothing that any of us will ever walkthrough.

Joseph Becker and Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, assistant curators in the Architecture and Design department, plunge the visitor immediately into the stormy world view of a thinker who once declared that “architecture and war are not incompatible. Architecture is war. War is architecture. I am at war with my time, with history, with all authority that resides in fixed and frightened forms.”

Neither the introductory wall text nor materials in the rooms provide any biographical data. One would never suspect that this iconoclast was a self-described “military brat “from Lansing, Mich., who began his career in the 1960s along a traditional path, in the office of Kevin Roche at Eero Saarinen& Associates, and ended up for several decades as a professor of architecture at Cooper Union in New York. Rather than trace the evolution of his thought, the curators have tried to unhusk the kernels of it, at least as revealed in his major post-1975 projects.

This approach has some advantages. He is presented as his ideas alone. On one side of the first room is a suite of 16 sumptuous drawings from his 1987 “Centricity” series. This futuristic vision of what appears to be a colony for a planet other than ours—in colored pencil, ink and sepia wash—is done in the calligraphic hand of a fastidious draftsman. It is easy to see why museums treat him as an accomplished artist, and why his imaginings, full of romantic ardor for all of their constructivist vocabulary, bring to mind Etienne-Louise Boullée, Giovanni Battista Piranesi and Vladimir Tatlin, as well as Henri de Montaut’s illustrations for Jules Verne’s novels.

On the other side of this entry room are Woods’s 1988 plans and model for the “Einstein Tomb,” an orbiting spacecraft in the shape of a cruciform cenotaph that would have carried the physicist’s ashes throughout the universe, were they not already scattered on the Atlantic Ocean.

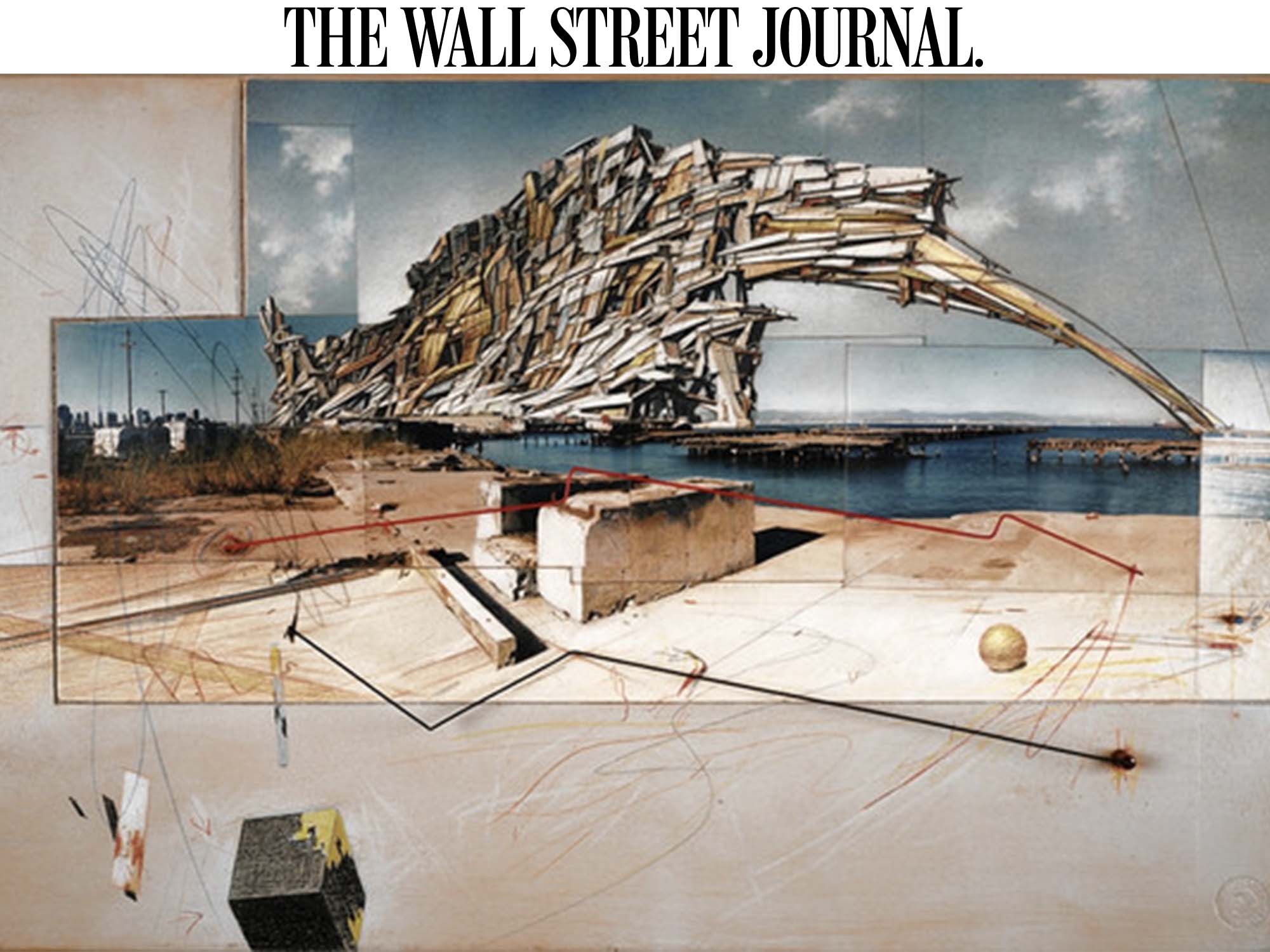

Instability was an accepted feature in the architecture Woods developed in the 1980s and’90s, and he believed that the places we inhabited should reflect this uncomfortable fact. The long main room of the exhibition contains plans from the 1990s for Berlin, Zagreb and Sarajevo in which he argued that these war-torn cities not be tidied up. The rifts of history should instead be reflected in the buildings. A drawing of a Sarajevo building from his “War and Architecture” series has left—or perhaps expanded—the riven facade so that a section protrudes in layered folds, like the tissues of an open wound.

What is missing from the show is any context for Woods’s unorthodox ideas. This is no doubt a deliberate attempt to honor his memory by presenting his work undiluted, without the usual trappings of art history. And it may be just as well that the curators don’t explore the imprint of French literary theory on American architecture in the 1970sand ’80s.

But there is no mention on the walls that Woods co-founded the Research Institute for Experimental Architecture or even that he was a deeply respected teacher. He is described as having had an “enormous influence” on the field. But how, why or on whom is left for the viewer to puzzle out. Only in the sketchbooks from 1998-2002 does one read the names of other New York or European architects (Peter Eisenman, John Hejduk, Aldo Rossi) who were contemporaries of Woods. However much of a maverick he may have been, these dreams did not pop into his head ex nihilo.

The curators present his ideas without a murmur of dissent or skepticism. His program of a new architectural outline for San Francisco, one that would not resist earthquakes but use their destructive energy to create new kinds of structures, sounds marvelous. Until one reflects that mutating architecture would likely be worse than the ills it seeks to cure. The son of a military engineer, he was oddly shy about mechanical specifics. “Einstein Tomb,” Woods mischievously submitted, would be transported throughout the heavens on a beam of light.

Not surprisingly, his thinking has been welcomed in film design and science fiction, where the laws of physics and finance can be overcome with CGI or words on a page. His rhetorical skills sometimes got the better of him. He wrote a lot of high-flown nonsense, such as “changing the way people change means changing the rules of change.” Like most utopians, even ones like himself who pledged allegiance to a bottom-up democratic politics, he could not help sounding at times authoritarian.

It is somehow fitting that the only Woods project that the architect lived to see realized was the 2011 “Light Pavilion”—a complex hole, really—within the Steven Holl-designed Raffles City Center in Chengdu, China. Planned in collaboration with the architect Christoph A. Kumpusch, it is a void crisscrossed by columns and stairs and illuminated from inside. As Woods wrote: “The space has been designed to expand the scope and depth of our experiences. That is its sole purpose, its only function.”

While many of his theory-besotted colleagues from the 1970s and ’80s—Messrs. Holl and Eisenman, and Daniel Liebes kind—went on to impressive careers, Woods was unable to make the compromises often required to build in the real world. “I’ve always worked, more or less—except in certain moments—alone,” he said in 2007.

In this intriguing exhibition, and in the moving tributes by his friends Mr. Holl and Sanford Kwinter (available on Youtube), one sees the lasting value, and the folly, of an architect pursuing such a devout and solitary life.