The Memphis Group luminary gets a showing at the event in Maastricht

By Serena Fokschaner

The architect, designer and thinker Andrea Branzi is a key figure in postwar Italian culture. A luminary of the 1970s Radical Design movement and early member of the 1980s Pop-inspired Memphis Group, Branzi’s quest to find new ways of making was life-long. In a career spanning six decades, his output — furniture, objects, urban planning — was accompanied by essays, books and voluminous philosophical treatises.

None of this makes Branzi, who died last year, easy to pin down. Even staunch supporters consider him “a bit of an enigma”, says Marc Benda, co-founder of the Friedman Benda gallery in New York. For The European Fine Art Fair (Tefaf) in Maastricht (March 9-14), Benda is showing a selection of Branzi’s work — art, furniture, needlework, lighting — which distils his experimental approach.

“Branzi was one of the most learned people I’ve ever met; capable of applying complex philosophies to everyday objects — and yet, the more you research him, the less clarity you have and the more you have to learn,” says Benda, who began showing Branzi’s work in 2010.

In 1985, with his wife Nicoletta Morozzi, he designed Animali Domestici, a still provocative collection of furniture that fused twigs and branches with laminates. The launch was accompanied by a manifesto of Branzi’s prophecies. “Post-industrial society and the electronic revolution will lead to more and more time at home,” he wrote, predicting “many different stylistic enclaves’’.

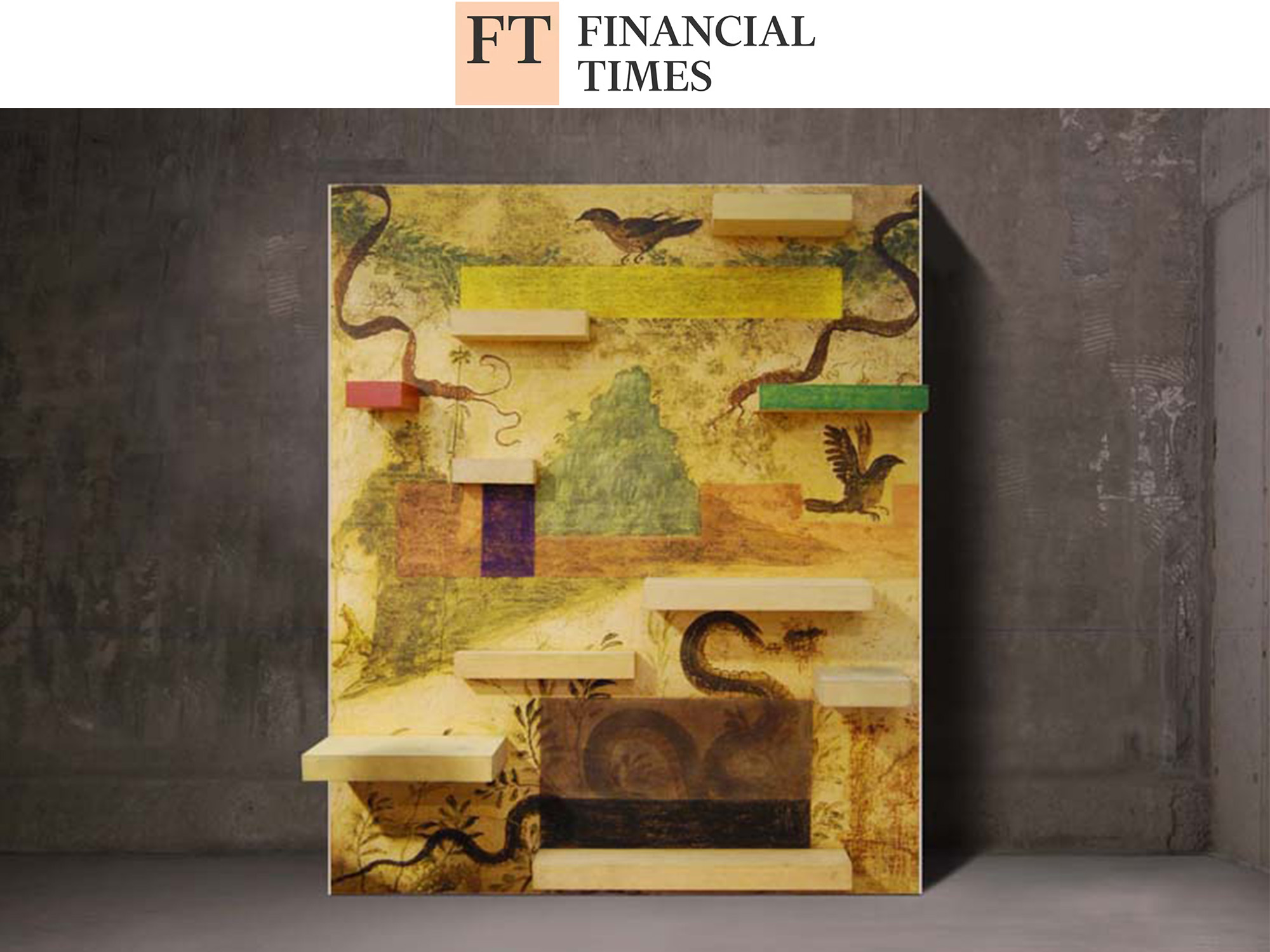

Tribalism, inclusivity, materiality — the designer anticipated many now familiar concerns. Branzi, born in 1938, created work that was highly conceptual, expressing multi-layered ideas about society. For example, the surreal 1967 Dream Bed was a riposte to the conformity and “cultural unity”, as he put it, of postwar Italian industrialism, and his musings on man and nature were manifested in pieces such as his Tree series: metal bookshelves entwined with birch trees. Wall 4featured a Pompeii-inspired mural, but was intended to display banal everyday modern objects as a comment on the myth of progress through history.

“It’s seductive to reduce a creative to a single talking point. Branzi resisted that,” says Benda.

Nina Yashar, founder of the Nilufar design gallery in Milan, says Branzi’s legacy of “pushing boundaries” endures today. “Experimentation . . . the integration of art and design. These principles are relevant in our current context,” she says, pointing out a growing awareness of“environmental and social issues — and the need for innovative solutions”.

As a student in Florence, Branzi began formulating the avant-garde theories that led to the setting up of the Archizoom Associati design studio — with Massimo Morozzi and Paolo Deganello — in1966. Branzi once described his leftwing compatriots as “snobs and Stalinists”. But together they challenged conventional notions of good taste by promoting the idea that everyday objects should have an almost talismanic resonance.

The Milan-based architect Stefano Boeri points to the influence of anthropology. “[Branzi] wanted the things in our homes to be like symbolic icons,” he says, and the studio referenced items such as totem poles or funerary urns.

Nonetheless, contradictions abounded. While the radicals rejected mass production, they embraced industrial materials. Archizoom’s 1969 Mies armchair — a witty nod to the architectMies van der Rohe — is made from rubber with an illuminated chrome footrest. The 1967 Superonda sofa was made from polyurethane. It is still in production today.

Many projects were never realised. Global Tools, an educational initiative, set out to change the way we live and work. No Stop City, in 1969, was imagined as a constantly evolving utopia with no buildings. Nomadic inhabitants could plug in to power and communications wherever they wanted.In an interview commissioned by Friedman Benda with architectural historian Dr. Catharine Rossi, Branzi compared it to the music of Philip Glass: “without an overture . . . or finale”.

“He was always interested in the continuation of things; rather than preserving them,” says Benda.

Branzi was in a period of questioning when he designed his one-armed Pigiama chair draped in floral pyjama-style fabric. By then, countercultural leftism had given way in Italy to the politically tumultuous 1970s. Having lost his belief that politics could offer a solution for societal ills, he lef tthe radicals to set up Studio Alchimia with Alessandro and Adriana Guerriero in Milan —describing it as a place “to realise experiments on paper and theoretical studies into real products”.

Equally provocative are the “fake” modern masters — Kandinsky, Mondrian — painted for the group’s Bau. Haus Uno and Due series. They reflected, says Rossi, the group’s “cynicism towardsthe originality . . . of the arts in the late 1970s”.

Yet Branzi was always able to combine the experimental with the commercial. Memphis, co-founded with Ettore Sottsass in 1980, became a household name with its vivid, postmodern designs. But Branzi became tired of what he perceived to be its overly formal, stylised wares.

In the later years, nature and the “neo-primitive” became a dominant theme. Animali Domesticiled to his Germinal series: aluminium benches with backs made of bamboo poles painted in vivid, totemic stripes. Branzi described them as the “new handicrafts” which “blur[red] the line between.