By Glenn Adamson

What if Picasso had never met Braque? What if Michael Jordan had gotten to play against LeBron James? What if cold fusion reactors actually worked? Historians call such scenarios ‘counterfactuals,’ sometimes using them as the basis for extended speculation. Such an exercise can be a clarifying reminder of history’s fundamentally indeterminate character. Counterfactual history can help bring key turning points into sharper focus. It can also be a springboard to the imagination, somewhat akin to the narratives advanced by Surrealism – which run alongside our world like a distorted reflection – but instead charts a coherent alternative, a fully mapped path-not-taken.

The present exhibition is entirely factual, of course, but it has something in common with such thought experiments. It takes place in the lengthening shadow of a year when the center did not hold. The project looks long and hard right into that unexplored landscape, whose full consequences are yet to reveal themselves, to answer a simple and poignant question – what would have been? The result may be surprising: an optimistic counter-narrative, which disproves any presumption of paralysis, instead projecting an impression of resilience, ingenuity, and even continuity. A gathering of generative energies, the project conveys not so much what has been lost due to the pandemic, but rather how much is still happening, in spite and even as a result of the crisis. Incidentally, it serves as an index – a kind of core sample – of Friedman Benda’s activity level over the course of a given year. The exhibition includes quite a few older works that would have been exhibited in various international contexts in 2020, but could not be; in this respect, it serves to unveil objects that ought to have been in the public’s view. It also shows that this year, designers have not stopped being creative, just because their exhibitions and publications and commissions and fairs have been delayed or canceled. They keep inventing beautiful things, made for us to enjoy. They keep thinking, keep offering provocation as well as respite, food for thought. Most of all, they keep reacting. And goodness knows, there has been a lot to react to.

Even as the coronavirus forced New York into lockdown– closing Friedman Benda for a couple of months, along with every other gallery in the city – the design community was reconstituting itself in new configurations. Conversation migrated almost immediately to online platforms (and it was in this context that the gallery launched its series Design in Dialogue, co-hosted by Stephen Burks and myself, featuring in-depth interviews with people from across the field and around the globe). What Would Have Been participates in this extension into the digital realm, as the exhibition takes place partly in the physical gallery space, and partly online. This hybridization is of course nothing new in itself; it reflects an intensification of a trend-line we have been on for some time. The trajectory is not so much for objects to dissolve into virtual space, as has sometimes been predicted, but rather to occupy multiple contexts simultaneously.

Designers have found various ways to respond to this accelerating tendency – the complex means by which their work now reaches the public. As galleries began populating the internet with “viewing rooms,” seemingly displacing the field of action from the physical to the virtual, materiality actually came to seem more important than ever, serving as an anchor for the free-floating, second-order experience of the digital ether. Designers seem to be more aware of this than anyone else. By making works that are carefully honed (Paul Cocksedge, Byung Hoon Choi), intriguingly improvisatory (Matthias Sellden, Misha Kahn, Toomas Toomepuu), or intensely process-led (GT2P, Thaddeus Wolfe), they communicate effectively at a distance while also insisting on the irreducible qualities of the object itself.

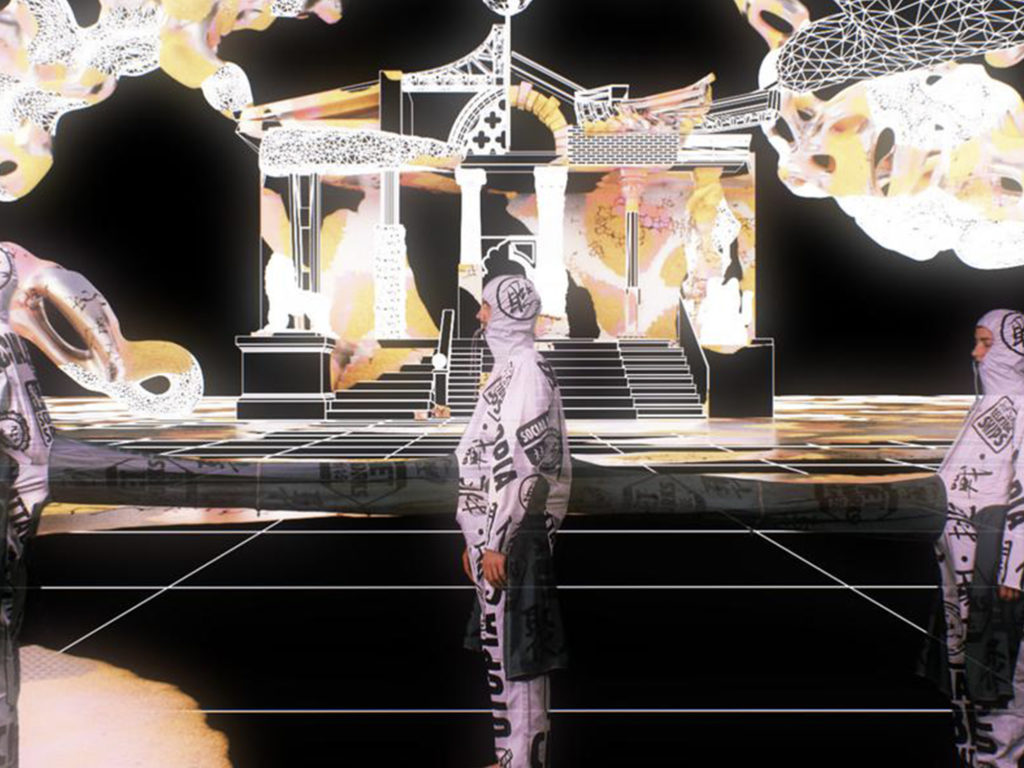

Some of the designers in What Would Have Been complicate matters still further, focusing on the encounter of object and image as a moment of creative possibility. In Faye Toogood’s collection Assemblage 6: Unlearning, planned well before the Covid-19 crisis but completed right in the heart of it, quickly-made maquettes are recreated at full scale in exacting trompe l’oeil. This immaculate re-conception dislodges our sense of what’s real, leaving intact only the core principle of creativity itself. OrtaMiklos, a young duo fresh out of Eindhoven Design Academy, make objects using low-fi techniques, then deploy them in dizzyingly sophisticated performances, videos, and digital spaces. Effectively, they are making props for a continuous, multi-channel piece of theatre. They addressed the volatile experience of 2020 directly, executing a whole exhibition in the conditions of lockdown, accompanied by a major digital work entitled Temple of Confinement. Daniel Arsham’s work, similarly, refracts into innumerable aspects – expressed as architecture, furniture, luxury goods, graphics, sculpture, set design, and more – while retaining an impressive intellectual consistency. If Toogood destabilizes representation, and OrtaMiklos identity, Arsham does the same for temporality, creating works that seem at once ancient and futuristic, adrift on the shoals of time.

In each of these design practices, the object (whether seen in reproduction or in person) is only one facet of a complex structure, a space that can itself be entered and explored. Physical and digital artifacts adopt intricate relations with one another, which may contain elements of commentary, reinforcement, elaboration, contrast, and critique. This year has, in a strange way, been an ideal moment to explore that kind of richness. For what could be more satisfying, when social distance is pervasive, than to connect with brilliant minds, across the whole range of their expression? Having said this, of course, the Covid-19 era has also been a time for introspection. The scale of the tragedy, the challenges faced by so many, the enforced isolation: it’s prompted many of us to reassess our most basic instincts about what is important, a habitual activity of artists. Even as expansive networks have been fragmented – including the social frameworks of studios, like those operated by Chris Schanck or the Campana Brothers – people have held their closest kin even closer.

Some of the most powerful moments in What Would Have Been reflect this kind of quiet, internalized energy. There is the work of Najla El Zein, for example, in which complex human relationships are transmuted into equally nuanced allegorical form; or the densely poetic, politically charged ceramics of Paul Briggs, which materialize a resonant protest against the imprisonment of Black Americans. Andile Dyalvane, at a time of social distancing, has conceived a powerful project about social connectivity. Entitled iThongo, or ‘Ancestral Dreamscapes,’ it is his personal adaptation of a ceremonial seating arrangement (a “holding space” for community and ritual, traditionally known as iHlelo). The project includes no fewer than seventeen sculptural seats, hand-built in ceramic; each is based on a traditional symbol of importance to the Xhosa people, which Dyalvane has adapted into sculptural form. Collectively, he thinks of the objects as “a gathering of dreams – seated in the soul, held by the spirits of our ancestors.”

As Dyalvane’s project demonstrates, even when times are at their hardest, artists respond, reaching out with their ideas to connect. This is also the raison d’être of Adam Silverman’s ambitious project Common Ground, which will be made from clay, water and wood-ash donated from all fifty American states, as well as six US territories. His plan is to transform this heterogeneous quarry into 56 sets – plate, bowl and cup – a metaphor of the hard work we must all do, to keep these United States truly united. The ceramics will be used for meals held around the country, cooked by chefs from different backgrounds, and attended by a cross-section of communities, once social distancing permits. One can only imagine, right now, just how miraculous that will feel.

For Erez Nevi Pana, the pandemic resulted in an almost magical occurrence. A major series of his work involves submerging pieces in Dead Sea, where they accumulate a salt carapace. Because he was not able to travel, several of them were left in the water for months, producing thickly patterned encrustations new to his work. They are like physical demonstrations of the butterfly effect – the scientific phenomenon whereby an action in one place can, through multiple compounding reactions, produce an unpredictable result elsewhere. In December, people in China began getting ill; in the summer, Nevi Pana – whose entire practice is attuned to planetary ecology – pulled his chairs up from the deep, and marveled at what he saw.

Samuel Ross is another artist who has carved himself indelibly into the story of this year. His new seating designs (in his words) “retain ancestral codes in relation to form, whilst reflecting a texture one must bear in the present to operate within such violently primitive, yet exceptional times.” emblematizing its potential to be a turning point for the better, a moment not of stasis, but of positive change. And this is just the sort of imagining that we will need, when we finally get out of this crisis, together. Right now – the fall of the tumultuous year 2020 – is a great moment to concentrate on hope, even if it is necessarily guarded. It is a moment for optimism, for ingenuity; a time to commune with individual minds, and the wealth of the collective. We ask what would have been, in part, because it helps us get ready for what might be; and in part because the question opens up a reality in which multiple, radical alternatives are intertwined: for art is the ultimate counterfactual.

This essay was originally published in exhibition catalogue What Would Have Been, Friedman Benda, New York, NY, November 2020.