Seph Rodney

Looking at Samuel Ross’s furniture artworks, bits of George Frideric Handel’s Messiah, the English-language oratorio composed in 1741, come wafting to my consciousness — specifically the aria “Every valley shall be exalted,” with its confluence of opposites. Its text (adapted from the Book of Isaiah) reads: “Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill made low, the crooked straight, and the rough places plain.” Yet, as I replay the music in my head, I realize that the language within the composition gives me rather the wrong tongs by which to grasp Ross’s work. Unlike the prophet’s messianic vision of transformation and redemption — which is inextricably bound up with a coercive, eschatological view of the future — Ross does not dissolve stark differences through stark opposition. In the series of works presented for COARSE, Friedman Benda’s second solo presentation of designer, artist, and creative director Dr. Samuel Ross, it’s not the case that the lowly is raised up, and the lofty is demolished. Instead, Ross brings together contrasting production methods, materials, traditions, histories, and holds them in abeyance, in irresolution.

These conflations, and the resistance of this work to an obliging dissolution of difference, is evident even in Ross’s terminology. To call something a “furniture artwork” is to subtly defy one of my foundational understandings of art: It’s supposed to be non-utilitarian, an occasion, an opportunity to consider and explore ideas that travel beyond the mire of our daily, corporeal reality. On the other hand, furniture is generally fashioned to meet our basic physical needs: to take the weight of our bodies when we are tired, unable, or unwilling to vigilantly maintain the responsibility of a certain posture. Chairs holds us above the ground when we no longer can or care to employ our own resources to stand. Tables keep things that are useful to us organized on a level plane, within easy reach. These realms of human making, furniture and art, typically address different parts of us — the intellectual and spiritual versus the material; the rarefied aesthetic versus the labored manual — and in doing so, suggest that we are right in separating out these aspects of ourselves in these ways.

But perhaps we aren’t.

In the designs themselves, even if viewers are unfamiliar with the formal dialects, it is fairly apparent that Ross is conflating forms that are not typically brought together in the same object, in most cases, even the same room. In a recent conversation, he talked about bringing together a “Gold Coast West African language in terms of forms, concaves, and convexes, and the softer subtler edges, the lack of 90-degree rigid angles,” with “modernist architectural forms.”

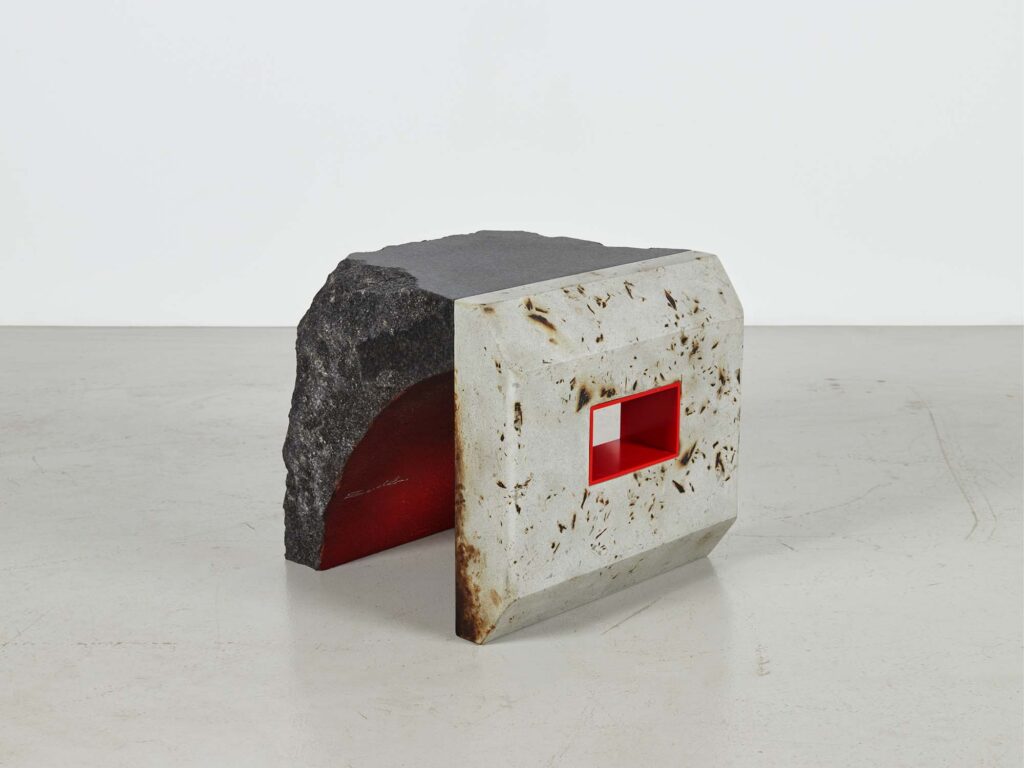

I can see his desire manifested in Birth at Dawn, an object consisting of Nero Africa granite, reinforced concrete, fired oriented strand board, honey and milk patina, painted steel, and polyurethane. In essence in looks like a stool, one half, the concrete side, cut and measured at precise angles, with a rectangular, steel-framed handhold carved into the middle, as if to say, “grasp me here; pick me up and take me where you will. I can be a tool of use to you.” The other side consists of more-or-less raw granite, colored red on the inside of its arc and pocked and stippled with the colors and textures of its origins in the viscera of the earth. This side looks like the object was hewn with hammer and chisel from a larger structure. It suggests a kind of vulnerability, as if it had just survived the brute force applied in the process of excision. Ross says that he has created “the meeting of these two vernaculars and voices,” that is, the vernacular language of West Africa, butting up against the forms of brutalist modernist design. Birth at Dawn has a flat surface where the granite has been milled and polished to a level and accommodating seat. I am sure I can rest myself on it, that it will bear my weight. But I’ve been taught that I should not sit on the art (or even touch it). So, what do I do with this?

I imagine Ross might say that the invitation his work holds out is a recognition that lived experience almost always denies a facile and simplistic utopianism, that it is a convergence of contradictions. Thus, he brings the contemporary head-to-head with that which reads as ancient, the intuitive with the planned, the colloquial with the standards and measurements of empire. The crooked remains crooked and the rough places do not abandon their character. The strategy Ross employs to keep these objects suspended between these two aspects of making is to use the aesthetic and architectural pidgins of brutalism and minimalism.

I can see the application of this tactic in Ross’s Slab, made of Verde Marina granite and painted steel. Slab makes a bench of two roughly hewn, inverted pyramid forms connected by a round, painted, perfectly straight steel beam polished to a mirror finish that has cored the two blocks of granite. (The visual reference here with the use of the synthetic green is to public spaces in the UK that tend to feature this kind of industrial form, so the work attempts to carve an intimate interlude out of disadvantaged conditions.) There is in Slab a lack of decorative flourish and a plain, even crude appearance that, like Birth of Dawn and the other pieces in COARSE, evoke a sere and resolute austerity.

This operation of combining the crooked and the straight doesn’t yield objects that are comfortable. I imagine that if I were to take my ease with a friend on Slab, rather than feeling coddled, it would not take long to feel the unyielding granite material press back against my flesh, making me intimately aware of my own fragility. And yet this is somehow right.

I am drawn to the sense of promise in Handel’s Messiah, the assurance that one day I will have resolution, and better still, this resolution will be universal: Every valley will be exalted. This comforts me. But my own lived experience is different. I wander among the coarse and unrefined, smooth and highly polished representations of the histories and traditions I’ve inherited and find those pieces of harsh, implacable beauty that I can sit with — that which holds me up a little bit above the ground.

This essay was originally published in exhibition catalogue Samuel Ross: Coarse, Friedman Benda, New York, NY, June 2023.