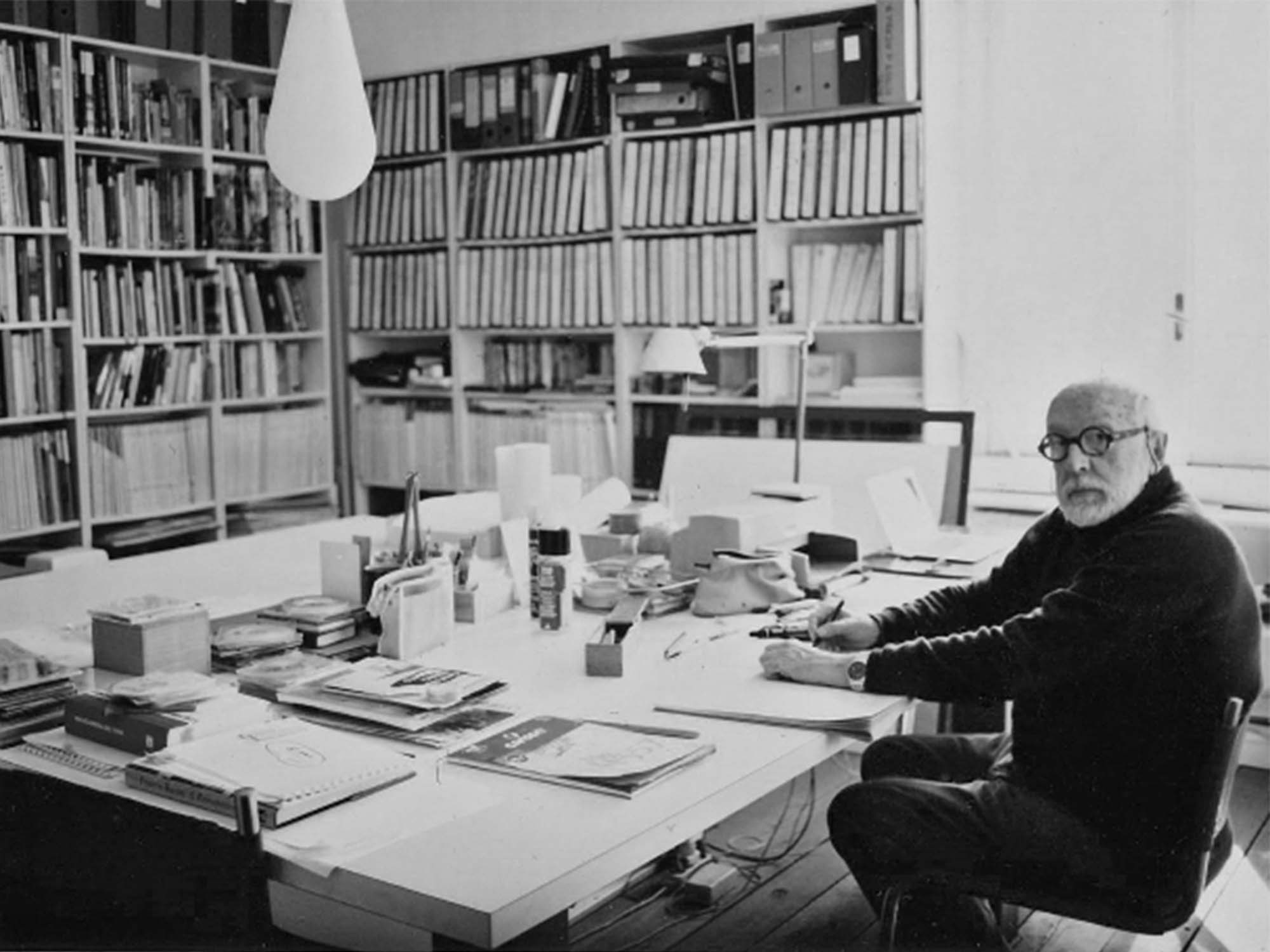

With Andrea Branzi’s passing, we seem to have lost many people at once: a creative genius who worked across numerous disciplines; an intellectual force whose ideas shaped the course of design history; and an essential observer of our times. Branzi was all these things. It is impossible to overstate his importance to the past half-century of design history, or really even to summarize it. Here we can offer just a few windows into the great architectural edifice of his life and work.

Branzi was born in 1938, in Florence, the epicenter of Italian art history. “Modernity was always something foreign,” he said of his birthplace, “something alien. And that was somehow to our advantage.” When he graduated from the Florence School of Architecture, in 1966, he and three founded Archizoom Associati, a research collective that charted a future which looks astonishingly like our present. They did make objects – among them, some of the era’s most enduring designs – but their principle focus was on urban space, which they conceived in radically integrative terms. Projects like “No-Stop City” (1970) postulated an ever-expanding domain in which conventional oppositions (public/private, industrial/residential) were completely dissolved. “We want to let in everything that stays outside the door,” they wrote in 1967. “Carefully constructed banality, deliberate vulgarity, urban fittings, dogs that bite.”

In succeeding decades, Branzi remained committed to the principle of collaboration. As part of the group Global Tools, he conducted experiments into the very basis of everyday life – a “technical back-to-zero,” as he put it. This emphasis on fundamental research established what Branzi calls the “culture of the project,” which he saw as defining the design avant garde ever since. This is a good way of understanding his participation in the influential radical design groups Studio Alchymia and Memphis, intentionally provocative undertakings that nonetheless became widely influential in the very domain of popular culture that had helped to inspire them.

In 1980s, Branzi’s intellectual leadership of radical design was confirmed by his role as cultural director of Domus Academy (founded in 1982 as an outgrowth of Domus Magazine) and his publications, including Hot House, published in 1984 –an indispensable guide to Italian radical movements. At the same time, he was developing his series Animali Domestici (“Domestic Animals”), designed in collaboration with his wife Nicoletta Morozzi. These furniture designs featured rectilinear modern forms impaled by unfinished logs, sticks, and wood offcuts, upholstered with loose pelts. They were the material extensions of his belief that one could contend with the catastrophic aspects of “post-industrialism” only by moving outside of the human perspective; and that this, in turn, required a shift from the architectural to the archetypal.

In more recent years, Branzi continued to use archetypes, which he defines as “very simple languages that however express a great universal communicative strength.” In the series Trees & Stones (2010-11), austere compositions of flat metal seem to conform themselves around organic specimens. His Plank series again features natural wood elements, but also sport vibrant color, like sculptural brushstrokes. The works present a physical metaphor for the artistic condition, with the moments of painterly liberty literally “framed” within a rigid order. And just last year, he completed a new research project expressed in three interrelated bodies of work: Roots, Buildings, and Bamboo, all of which once again placed found organic materials within a fabricated matrix. “Overcoming the limits of technologies and professions, we consecrate ancient trunks and barks that will never reproduce,” Branzi wrote at the time. “Infinitely different series, marked by unpredictable colors and grotesque objects, they save the world from the infinite ugliness of that which exists.”

While always alive to the immediate political and cultural context, Branzi was a true visionar: so many of his writings and artifacts seem astonishingly prescient. In retrospect, we can understand them as the source code of the contemporary design avant garde, with all its flexibility and innovation. This was the lesson that Branzi imparted to us: it’s not through opposition that insight happens, but in the elastic space between.

DESIGN IN DIALOGUE

Rewatch this three-part Design in Dialogue interview, which offers a conversation with the great luminary of Italian design and architecture, Andrea Branzi. In this interview, Dr. Catharine Rossi – a UK-based design historian, and associate professor at Kingston University – speaks with Branzi about his long and influential career. Interviews are conducted in Italian with English subtitles.

Part 1 – Origins: Andrea Branzi on Radical Design

An introduction to Andrea Branzi’s background, early career, and involvement with radical design collectives such as Archizoom, Global Tools, and Alchimia. Read translated transcript HERE.

Part 2 – Andrea Branzi’s Design Approach: No Stop City and Beyond

Taking one of his most well-known projects, No Stop City (1969), as its departure, Branzi presents his ideas about urbanism and the history of utopias, framing these issues in relation to the contemporary politics of neoliberalism. Read translated transcript HERE.

Part 3 – La Cultura del Progetto: Andrea Branzi on Designing Culture

The series concludes with a conversation about broader cultural understandings of design, taking in the full scope of Branzi’s expansive work – including his roles as curator, writer, editor, and educator. Read translate transcript HERE.

ESSAY BY ANDREA BRANZI, MILAN, 2016

INTERIORS

Design culture has long remained linked to twentieth century codifications and the myth of the industrialization of human space; codifications that were based on geometries and materials functional for mass production.

In the twenty-first century this dogma has begun to show cracks, and the difference between mass-produced objects and unique pieces, between machine made items and handmade artefacts, is not so important — what matters is their ability to create an emotion, without any fear of commingling with art and nature.

The loneliness of contemporary design, isolated from the creative activities that surround it, is a mindset that must be broken; new aesthetics, new materials, and an entirely new dramaturgy are pressing to renew the human habitat.

Classical Modernity has remained indifferent to the tragic events that have marked the twentieth century: two world wars, mass exterminations, atomic conflicts, the great left-wing and right-wing dictatorships; this indifference to Real History in favor of the History of Discipline must now be left behind.

According to tradition, the difference between art and design is that art cannot be touched, while design is meant to deal only with functional mass-produced objects; when these conventions are obeyed, the human habitat is impoverished and shies away from new experiences.

Interiors seeks to overcome these limitations by using art for its application possibilities, and design to create artistic objects. The twenty-first century teaches us that in the world of design the restrictions imposed by tradition must be overcome, following the transformations that characterize our society, where boundaries are blurred and everything is intermingling and expanding.

Objects have always been “living” presences in the human habitat; presences with which, since the dawn of time, we have established complex relationships of a psychological, symbolic, and poetic nature: in this sense, objects are never just simple tools, they are fragments of an anthropological universe, a universe at the same time material and immaterial, functional and superfluous, about which we still know very little.

Design objects are the result of the artistic use of technology, and the technical use of art, and for this reason they are always mysterious presences, sometimes indispensable and sometimes unnecessary; yet in the history of the world no two design objects have ever been identical.

In our product-oriented civilization, the ungovernable flow of industrial objects, so transferable, so exportable, so transient, has transformed our cities into virtually boundless areas of exchanges, information, and trade. It is safe to say that if in the past the city could be defined as a stage for architecture, it is now a “personal computer every twenty square meters.”

Our space is crisscrossed by a stream of relationships produced by the seven billion people inhabiting the planet, each one representing an exception, a variant, a personality that affirms its exclusivity through the objects it chooses to be surrounded with.

For this reason, objects have become a presence that is sacred because it is linked to the sacredness of man: they continue to live beyond the scope and time of their daily use. They have no knowledge of the night because in the night they survive, unmoving, unchanging, alive even after their own death.