By Glenn Adamson

The design avant garde has taken a turn. As little as ten years ago, there was a widespread assumption of a single, shared framework of relevance, at least in the USA and in Europe. That canon was defined primarily in reference to modernism, whether in a spirit of allegiance or opposition: on the one hand, a loyal extension of rationalist, functional principles; on the other, a critical response to those premises. That dialectical paradigm, capacious and generative as it was, now feels awfully limited, and surprisingly remote. It obviously cannot accommodate the globalized design scene we have today, with its tremendous diversity of perspectives. Increasingly, and swiftly, it has become clear that the lifeblood of progressive design runs though many more arteries.

Javier Senosiain is emblematic of this shift in perspective. He is best known for El Nido de Quetzalcóatl (The Nest of Quetzalcoatl), an ever-evolving complex of residences, gardens and parkland in Mexico City. El Nido is at once a series of caverns, a baroque edifice, and a futuristic vision; sculpture, architecture, and landscape. It is both welcoming and sublime, extraordinarily sophisticated, yet gesturing beyond that which we customarily call civilization. And this is only one of his projects, albeit the largest and most ambitious. Senosiain’s ouevre is as enormous as it is experimental, and promiscuous in its aesthetic effects. Yet his creations do have in common an intuitive quality, a feeling of having grown incrementally out of the nurturing earth, and from a seedbed of vernacular artisanship. He has worked closely with his team of highly skilled fabricators for decades now, developing distinctive techniques – above all, the polychrome glaze ceramic mosaic that has become a signature of his work – and developing, too, an implicit collaborative methodology, which allows for ongoing instinctive exploration.

The power of this productive vision is undeniable – to experience El Nido is to have one’s view of architectural possibility dramatically expanded. Even so, Senosiain has long been treated as a fascinating but somewhat eccentric figure on the international stage. Mainly he is understood as the last exponent of a current known as Arquitectura Orgánica, itself unjustly marginalized. This lineage traces itself back to Antoni Gaudí – the ultimate outlier of architectural history – via figures like Mathias Goeritz (who taught Senosiain) and Juan O’Gorman. One can also see affinities in Senosiain’s work to the great heterodox colorist Luis Barragán, and further afield, the extraordinary fantastical environments of Niki de Saint Phalle. For all of these figures, architecture is not a matter of problem-solving or even form-giving, but rather an undertaking of greater cultural profundity. The task is to channel deep forces that can only be felt, like tremors. The symbolic allusion, at El Nido, to the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl – the Feathered Serpent that presided over creation – is typical of Senosiain. While very much meant for day-to-day inhabitation, his buildings imaginatively inhabit farflung realms: the domain of myth, the far reaches of time, when dinosaurs rather than humans ruled the planet.

Until recently, one could experience Senosiain’s work only in Mexico, at El Nido or one of his other projects. This changed in 2022, when he participated in an important exhibition entitled In Praise of Caves at the Isamu Noguchi Museum in New York, which explored the subject of Arquitectura Orgánica. As a centerpiece for the show, he created a monumental serpent, a Coata, sheathed in glittering red mosaic that is equally suggestive of scales and feathers (dinosaurs had both). Concurrently, he made a related work, initially exhibited in Montreal; and he is now developing a third serpent, his largest to date, which will be presented in the exhibition Ground/Work 2025 at the Clark Art Institute. Vivid purple in hue, it will be positioned in a reed-lined pond outside the museum, its coils breaking the water line as if it had only just emerged from the unknown depths.

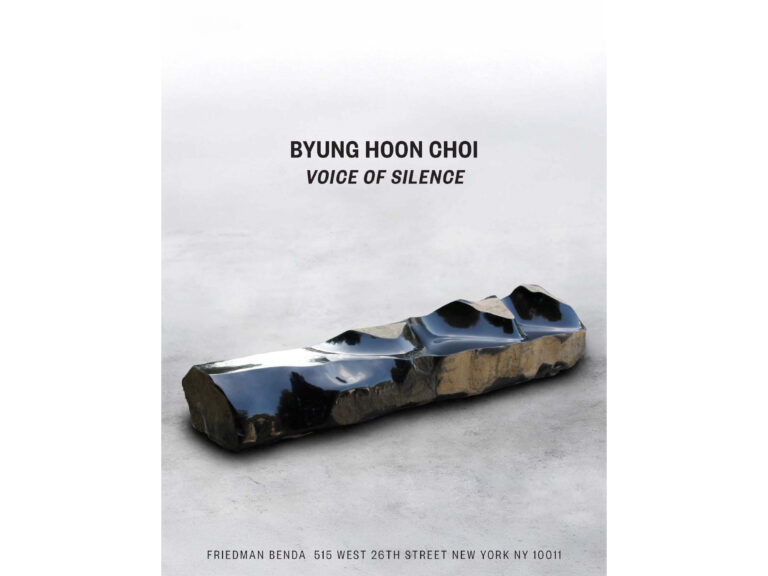

Alongside these autonomous sculptures, Senosiain has increasingly been channeling his creative energies into objects of functional scale and conception. This is not wholly unprecedented; his architecture often includes bespoke and built-in furnishings, and one could say that all his buildings have a compelling “object quality” to them. But only now are these emanations of his atelier traveling the world, as if under their own propulsion. In January 2023, his seating sculpture Warm Colors was presented in the Friedman Benda exhibition Everything Here is Volcanic, an important survey of contemporary design practice in Mexico curated by Mario Ballestreros. The work is a serpentine muscular gesture with a daringly cantilevered upper half, formally close to the Coatas. It is similarly “skinned” in glazed shards, the palette bearing out the promise of the title. The substrate is composed of reinforced “ferrocement” and a glinting, glass-enriched grout. The colors flow unimpeded across the surface, articulating every one of its powerful, twisting contours. Look at it from a certain angle, and you may be reminded of Verner Panton’s famed S-chair; from another, the lolling tongue of some great beast; from yet another, a lick of dancing flame, or a blasted tree leaning permanently back, back, back, on a high windswept plain.

Among Senosiain’s other recently completed works are a sensational mirror, which again takes the serpent as a primary motif; a mushroom-shaped table with a cluster of round, flat-topped seats around it; and a set of concrete, mosaic-covered pots inspired by ammonites (the iridescent fossils of enormous cephalopods, which predate even the dinosaurs). To enumerate this iconography, though, hardly does justice to the majestic strangeness of these works, which are, like Warm Colors, both literally and figuratively multifaceted. The overlapping, perforated form of Snake Mirror, for example, could be read as an archaeological site plan viewed from above – perhaps of the celebrated “serpent mounds” which mark certain ancient American burials. The Fungi Kingdom Dining Set does suggest propagation on a damp forest floor, but it also has an orbital dynamic, more cosmic than earthly. And the Ammonite Pots, which draw on the homely intelligence of vernacular Mexican craft, are also magical, like rainbows somehow caught and held fast.

The rich multiplicity of Senosiain’s metaphors set him well apart from the modernist legacy. This distinction is as much ideological as it is artistic: he is rightly critical of the way that functionalist architecture and design have been implemented across the globe. What had begun in the early twentieth century as a family of wayward, radical forms – organic in their conception, intuitive in their logic, rich in their metaphorical implications – gradually became a repetitive formula, repeated endlessly and often thoughtlessly, with efficiency rather than experimentation as its goal. Senosiain vehemently rejects that false rationalism, instead embracing an alternative sort of pragmatism, in which time-tested archetypes continually take on new life.

Thus there is more to Senosiain’s recent rise than a belated global inclusiveness, or an interest in previously disregarded histories. He also incarnates a set of values that are provocatively at variance with our short-term, attention-starved culture. He thinks in terms of deep time, not only past – when dinosaurs ruled the earth, when the Aztecs had their empire, when Surrealism was emergent – but into the future as well. To be in his work’s presence is to feel the fleeting, self-absorbed nature of many present conversations. After we’re gone, his creations will endure to be wondered at, much as we regard T. Rex skeletons and the pyramids of Teotihuacán. Out there in that possible future – which may not be too far distant, in the grand scheme of things – when our descendants encounter Senosiain’s creations, they may think a bit better of us. They’ll see that some among us sought to truly understand the human condition, which is after all only one tiny piece, one glinting shard, of a much bigger story.