By Glenn Adamson

“The children who love printed scraps, and paste them into scrapbooks printed with the legend ALBUM, bring greater hope to artists than any plethora of critics and museum directors.” That is the Danish artist Asger Jorn writing, in 1941. One can file his thought right alongside those of many other artists at the time, who had a similar affinity for the art of children, and the self-taught: what Jean Dubuffet evocatively called art brut. The impulse arose at a uniquely traumatic time in history, in the wake of the industrialized mass murder of World War II. “Civilization” seemed already to have indicted itself, and perhaps to have reached a point of no return. Attraction to what was then called the “primitive” was a widespread, multigenerational, and cross-disciplinary response. It was felt not only in Jorn’s immediate circle – most famously, Jean Dubuffet – but also by a diversity of other figures, among them painters from Pablo Picasso to Jackson Pollock, and architects like Le Corbusier and Charlotte Perriand. All saw raw intuition, primary invention, even anti-intellectualism as a necessary step at an urgent time. In the wake of war, it was vital to reset human expression itself. So they sought to unlearn all they knew. To go back to basics. To begin again.

Fast forward to 2020. Our moment has brought no new World War – let’s try to keep things in perspective – but it does seethe with conflict, complicatedness, and contradiction. On the positive side, we have unprecedented access to information – but even this can seem overwhelming, a mental diet of too much, too fast. This is the large but necessary backdrop to Faye Toogood’s new body of work. It is the outcome of long thought, consideration and experiment. About three years ago, Toogood decided she’d had enough input. Like Jorn and Dubuffet, she wanted to strip her working process back to its essence. The timing was right for this in personal terms, as well, for she had just become the mother of twins: a natural time for a reset. So, she determined that she would attend no exhibitions or events, and keep her consumption of other designers’ work to an absolute minimum. She would move forward by taking a big step back, to the ground zero of her own creativity.

For any designer, this would be a big decision; it’s a field that runs on influence, the exchange of ideas. For Toogood, it arguably had even greater significance, because she is so very adept at tuning into what’s happening around her, and responding in original ways. She started her career startlingly young, as a magazine editor. After about a decade of that, she started her own fashion line, then founded a Janus-faced studio, half-devoted to developing garments, and half to others genres of design (interiors, furniture, ceramics, and other objects). In all this work, Toogood has partly responded to the zeitgeist, partly shaped it.

Even as she has honed her receptivity, though, she has placed an unusual emphasis on the exact opposite: naïveté, a certain innocent eye. You can see this quality in her most important works: the Spade chair, her attenuated take on a farmer’s milk stool; the Elements table, which has the geometric simplicity of a child’s plaything; or her Roly Poly chair, with its friendly contours, a hug in the shape of a seat. The sensitivity that results in such ideas is a fragile thing, as Toogood knows well. So she has created a conceptual parameter for herself, in which her instincts can be protected: she calls it the Assemblage, a group of interrelated objects which share a common aesthetic. She has created five such collections before; in each one fresh ideas are introduced, while other typologies are reprised in a new key. Each Assemblage has a quasi-narrative structure, too, which infuses its constituent objects with meaning. But the format’s most important role is to free Toogood from the exigencies of a particular commission, to secure her free space to explore, so that she can follow her own lead wherever it takes her.

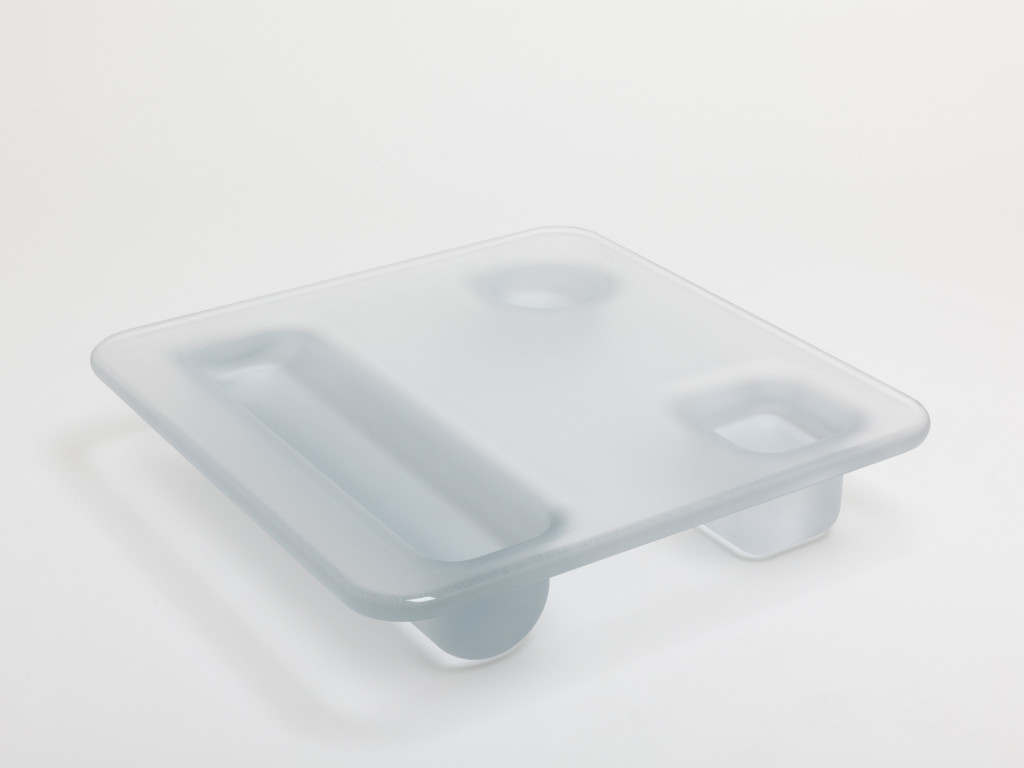

Assemblage 6 is, in one way, just another spin of this creative wheel. Toogood expressly devised it as a zone for R&D, trial and error, and form-generation. But it is wholly unlike all of her previous Assemblages in the rigor of its conception and the focus of its outcomes. As its title, Unlearning, suggests, it reflects Toogood’s desire to shed the sophistication for which she has become so well known. Each object in the collection enshrines a specific moment of intuitive play. Her first step was to make a large number of quick, rough models, in the materials she typically uses for this purpose: cardboard, wire, various kinds of tape, clay, paper, and canvas. Normally, these initial sketches would be developed to prototype stage, but for Assemblage 6, Toogood stopped the process right there, and did something totally unexpected. She picked out her favorite maquettes and then recreated them at the scale of functional furniture.

Preserving immediacy was vital, at all stages. From idea to model, the only filter was two hands; from model to finish work, the only filter was the fabrication process, the only constraints, the materials chosen and the makers’ skills. Thus the original maquettes, fragile little objects which might otherwise have been thrown into a box or discarded, were instead treated as sacrosanct: relics of sorts, which must be paid due deference. Each was imitated with exacting precision at enlarged scale, creating an Alice in Wonderland effect – an impression enhanced by Toogood’s decision to present the objects on gray MDF, the material she prefers for work surfaces. Viewers of Assemblage 6 may feel that they have been miniaturized and allowed to walk around on her studio tabletops. This is not just a clever bit of trompe l’oeil, though, but an act of conceptual time travel, back to an original moment of inception.

Initially, the idea of replicating the maquettes was just that, an idea. To have any real power, it needed to be executed with all the finesse and expertise that Toogood has brought to all her previous work. So every object included in the Assemblage took an epic journey from initial conception to final realization; the duplication of each material was its own independent research project. Cardboard was transformed into patinated bronze, tape into resin. Blacksmiths were enlisted to recreate twisted wire in wrought iron. Canvas plays itself; one of Toogood’s go-to materials, often used in her garment designs, it has been treated with a resin binder, to stiffen it. It turned out that canvas was also the best option for reproducing the effect of masking tape; covered with a thin layer of fiberglass, it recreates the matte texture and the coloration of the original material with uncanny accuracy. The specificity and diversity of these material solutions lends Assemblage 6 a variability that jousts fascinatingly with its single, unified premise.

Previously, Toogood’s collections have been strongly guided by a theme – Assemblage 5 , for example, which was presented at Friedman Benda in 2017, was occult in feeling, inspired by the elements of water and earth and the pervading light of the moon. It was an associative process, not totally dissimilar to the use of “mood boards” of fashion. Here her approach is very different, more like the more rigorous methodologies observed in conceptual art. To the extent that Unlearning had a mood board, it consisted of things like TRASH, a sculpture by the British artist Gavin Turk, which is a dead-on replica in bronze of a cinched black plastic garbage bag filled with unseen refuse. Toogood also had in mind certain rustic furniture, and archaic objects, which she valued for their immediacy – things that felt like they had arrived all at once, without reflection or refinement. Things that seemed to tap into the essential human capacity to invent, and give shape to raw matter. For another project, at another time, she might have been more direct in her borrowings from these sources. But for Assemblage 6 she wanted something more sui generis, and arguably more intellectually arresting: a mediation on what creativity looks like, an invitation to consider why it matters.

There is a deadpan joke, in this project, about value: such care and expense lavished on imitating such poor materials, cardboard and tape, wire and simple cloth! But that’s the whole point. The twisted scraps of the maquettes were anything but worthless. They reflect the most valuable thing we have: unfettered creativity, from which flow all human communication, connection, and expression. That this can be achieved with a few everyday materials, in a few moments, is indeed remarkable. Nor is it accidental that Toogood employed this vocabulary at a volatile time in history. After all, the collection was developed during the same period that Brexit was dividing hearts and minds in her home country – a flood of conflict and ill-will, which had left so many feeling raw.

Assemblage 6 laps gently at this situation, floating in at the high tide, rather than confronting it outright. Toogood accepts that the work, so edgy by her standards, does reflect the anxious tenor of the times. For her, the whole collection is pervaded by a sense of vulnerability: “of the original materials used for the maquettes; of myself as a designer, exposing the most private part of my process, the first iteration; the seeming vulnerability of the final pieces.” Yet of course, appearances are deceiving. The finished works are extremely robust. We might take them as physical metaphors for the strength that comes through self-exposure.

Thus the apparently simple objects in Assemblage 6 are pitched in a complex field. They stand ambiguously between alpha and omega, inhabiting neither position fully: the raw and the refined, the momentary and the monumental, and expressionistic and the austere, fragility and permanence. And this very complicatedness is part of the message. Each of the objects in the collection derives from an instant of quiet improvisation. In honoring that private and transient experience, Toogood is showing us how much is contained within it. That is what Asger Jorn and his fellow lovers of art brut sought, too. They distrusted academicism. They did not want to make the mistake of valuing knowledge for its own sake; indeed, they saw that it could be a prison.

Only a very sophisticated artist would have thought to frame such an argument, of course; but sophisticated artists need freedom, too. In Assemblage 6, Toogood has given herself that opportunity. She has taken herself to a place of supreme importance – right back to the beginning- and from that vantage, asked herself fundamental questions about her own practice, and the discipline of design itself. Toogood has dared to reinvent herself; and she has made the most of it.

This essay was originally published in exhibition catalogue Faye Toogood | Assemblage 6: Unlearning, Friedman Benda, New York, NY, September 2020.