By Glenn Adamson

Beauty, they say, is in the eye of the beholder. So too is contemporaneity. For many involved in design today, relevance is a rapid-fire affair. Fast fashion, just-in-time manufacturing, seasonal collections, trend forecasts: all come and go at speed. In this ongoing procession of planned obsolescence, ideas abandoned as soon as their value has been extracted, leaving a churning wake of physical waste behind. But there is another way to understand “the now.” It need not be experienced instantaneously, as the briefest of intervals between past and future. The present moment can also be viewed expansively, extending back decades, centuries, even millennia, indeed, across the whole domain of shared human ancestry. After all, against the backdrop of geological, planetary, and cosmic time, homo sapiens’ seven-odd-million years on earth is only the briefest of intervals.

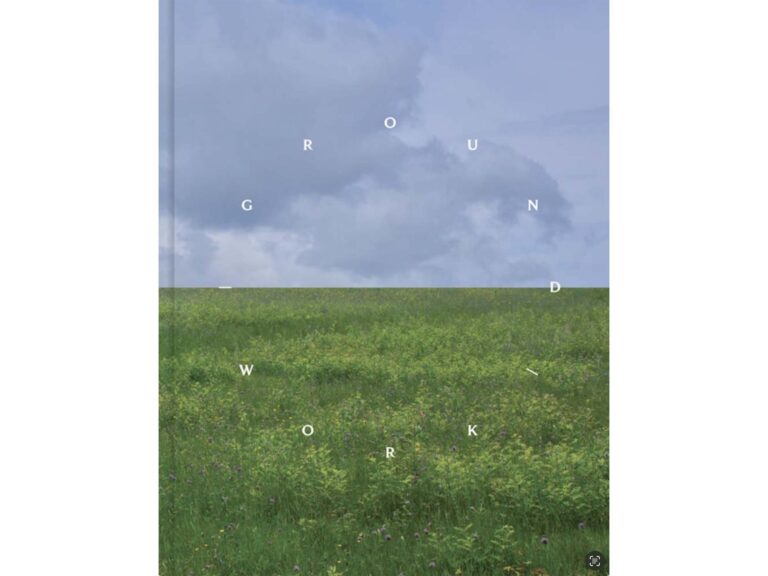

It is within this grand scheme of things that Faye Toogood operates has created Assemblage 7: Lost and Found. Her framework of reference spans deep time, equally taking in modernist abstract sculpture, seventeenth-century chests and chairs, medieval church architecture, and ancient standing stones, and finding the commonality between these apparently distant things. Her carefully chosen term “assemblage,” with its implication of gathering and arranging things, is to be distinguished from the more conventional idea of a collection. She is among other things a fashion designer, and in that context necessarily operates in relation to the industry’s demanding Spring/Summer, Autumn/Winter rhythm. When creating objects, though, she is free to adopt a more encompassing approach. And so she does, steady as she goes.

The new Assemblage is only her seventh, after fifteen-odd years of object-making, and it has been gradual in its formation. It evolved organically from her previous Assemblage, (“Unlearning”), which was similarly based on small handmade models, and had its own long inception. As is obliquely implied by the title “Lost and Found,” Toogood is returning to forms and procedures that have preoccupied her throughout her career, previously set aside and now picked up again for new use.

For example, the distinctive carved oak that features so prominently here has its roots in her project Cloakroom, presented at the V&A during the London Design Festival in 2015, for which she created a series of wearable garments as well as sculpted equivalents to them: in oak, in marble, a carapace of metal rivets. For Assemblage 7, she returned to the same artisans who had done the woodcarving for that project – a family-run firm in Somerset who specialize mainly in historic interiors – and embarked on a much more ambitious collaboration. The primary timber used is European oak (Quercus robur), which has a strong pattern of overlaid flecks and rays. As the wood must be laminated together from 90-millimeter boards, the construction – especially those with multiple exposed faces, like the Heap armchair – requires intensive figure-matching so as to unify the composition, rather than creating a checkerboard effect. The monolithic impression is further enhanced by a custom shellac finish in a warm, reddish brown, redolent of how Tudor-era furnishings might have looked when they were new. Assemblage 7 also includes objects fashioned from bog oak, sourced from Ukraine – wood that’s been sitting in a peat marsh for time beyond reckoning, perhaps thousands of years. Protected from decay by its immersion, it undergoes a process of partial fossilization while absorbing tannins from the vegetal muck, becoming extremely hard, dense, and rich in color.

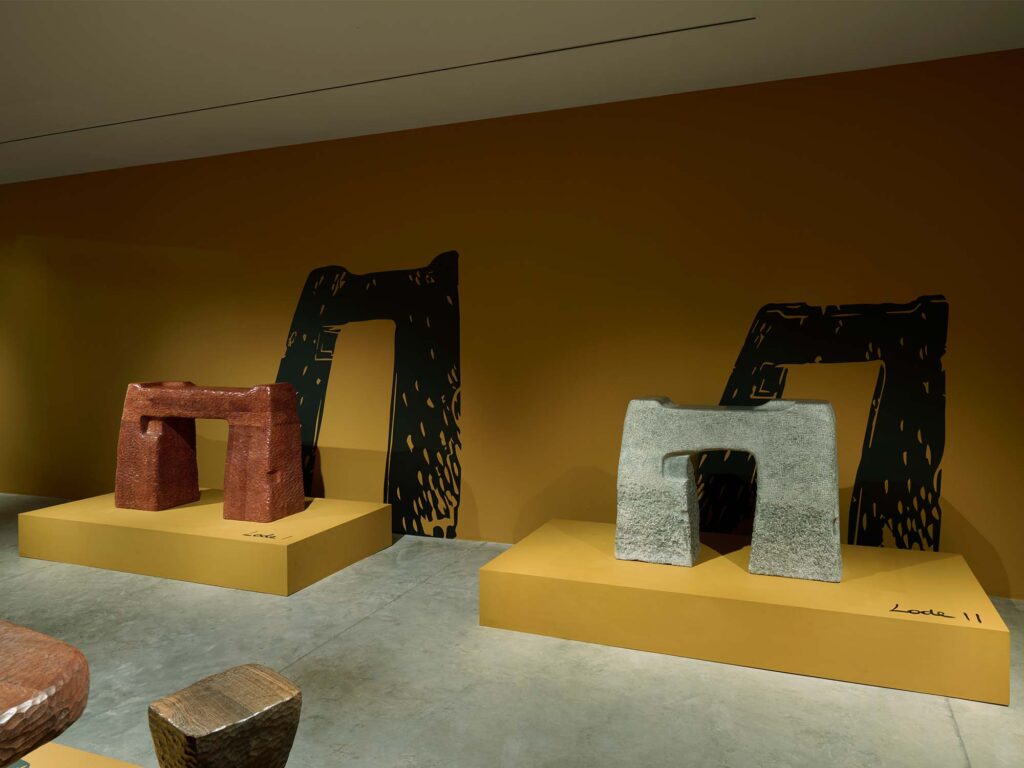

As for the other signature material in Assemblage 7, Purbeck marble – it makes bog oak look brand new. Named for the peninsula in Dorset where it is sourced, the stone is not a true marble but a deposit of limestone and fossilized shells, which formed in the ancient seabed over the course of about six million years. It has been quarried as a decorative stone since Roman times, and can be seen in many of Britain’s most important medieval buildings, among them Westminster Abbey. It is easy to see why it has had such prominence: cutting and polishing reveals a surface of lace-like pattern, punctuated by the intricate whorls of individual shells. This too is a difficult material to shape, recalcitrant and heterogeneous, and to work with it, Toogood turned to a London-based stone shop that has extensive experience in working for artists, as well as in architectural restoration. As with the oak boards, multiple pieces of the stone must be combined into the monumental works – the “bedding” of the Purbeck marble is relatively shallow, with seams of clay running through it, so there is a dimensional limit to the material. Yet they are combined into a powerful integrity; these works are built to last over centuries and more to come.

Whether the finished result is to be in timber or stone, Toogood and her team follow a similar procedure. Each design is developed first in clay, by hand, and then recreated in the studio at full scale. This prototype is made in polystyrene foam using hot wires and files, a relatively expedient process that preserves the intuitive freshness of the original. The foam is then delivered to the fabricators, who follow its every curve and twist faithfully – the slightly wobbly contours of that first tiny clay model still present, even as the form is rendered in a far more obdurate material. To index this process of translation – and emphasize the artisanal quality of the objects – tool marks are left on the finished piece, rougher at the bottom and transitioning to finer, subtler faceting and then a smoothly polished surface. Especially in the case of the Purbeck marble, the effect is positively archaeological; one feels the forms emerging out of the ancient mass, hard-won, into the light.

The present exhibition marks the third presentation of works from Assemblage 7, a further layer to a stratigraphy. The first five pieces (four in wood, one in stone) debuted in 2022 at Friedman Benda’s Los Angeles location. The following year, in the exhibition Mirror Mirror: Reflections on Design at Chatsworth, which I co-curated with Alex Hodby, a larger grouping was shown in the great English country house’s chapel and adjoining Oak Room, spaces replete with baroque detail and historic ambience. As Toogood’s creations were put into place, a strange inversion occurred. Though they had been completed only weeks earlier, they made their surroundings (which date to the 17th and 19th century) seem brash and new. It was as if they had always been there, and Chatsworth had been constructed around them. They felt, too, like portals to elsewhere: to open fields, tilled by countless generations; and to the sacred circle of Stonehenge, where rites we can only guess at were performed over the centuries.

Now these physical profundities have made their way to New York City. If anything, they seem even more needed here, in a metropolis that rushes past its own past, hurtling ahead to the next, and the next. Standing in the exhibition at Friedman Benda, taxicabs passing by on the street outside the gallery, you feel the true complexity of time, the paradox of the now, which is always at once a layered accumulation and a fleeting instant; an infinite assemblage – and a single flash of illumination.